A state information privacy law that went into effect Sept. 1 requires entities including businesses and government bodies operating in Colorado to take reasonable security measures to protect personal identifying information they collect from residents. But the law has left the definition of “reasonable” purposely malleable. And as Squire Patton Boggs associate Brent Owen pointed out, the difficulty of assessing reasonableness after an information breach happens adds another layer of uncertainty to defining the standard.

“Reasonableness once you have a breach is much harder to define, because you’re looking at a security protocol that necessarily failed,” he said. “What looks reasonable on the front end, when faced with a class action and concrete harms to Colorado consumers, may not appear reasonable.”

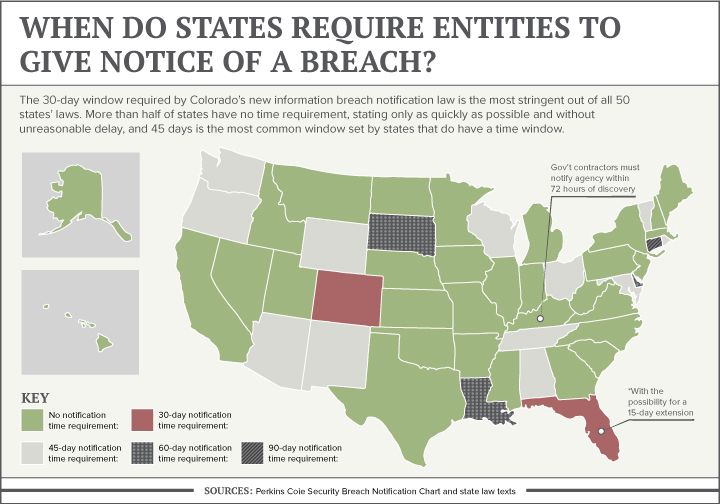

All 50 states have now passed laws governing breach response for either companies or government bodies. But Colorado’s is the most stringent, with the shortest notification time requirement of 30 days from discovery and a wide-reaching definition of personal identifying information from Social Security numbers to fingerprints. The statute also requires entities to have a policy in place to destroy information that’s no longer needed.

Last week, Attorney General Cynthia Coffman’s office published a list of frequently asked questions for entities. Among them is guidance for entities who must notify the attorney general about breaches affecting more than 500 Colorado residents.

It calls for entities to provide information such as the date they discovered a data breach, the date the entity gave notice to impacted Colorado residents and a copy of the notice, and the number impacted.

David Stauss, a partner at Ballard Spahr who had a hand in drafting the bill, said the new law left the requirement for entities to take reasonable measures in protecting consumers’ personal identifying information intentionally ambiguous to account for differences between entities, such as the types of information they collect and the resources they have.

“You’re going to judge Google a lot different than you’re going to judge a mom-and-pop store,” he said. “Google is getting a lot more types of personal information than a mom-and-pop store will. And so the sliding scale, they wanted it to be flexible to be able to call balls and strikes on those issues.”

Owen said he believes a standard of reasonableness for information security measures will be defined further by the courts in cases where breaches occur. He added that standard will likely be more stringent than what the legislature has established.

“Colorado courts will analyze what is reasonable in the context of consumers’ personal information having been released and them having been harmed,” he said. But further guidance from the attorney general about expectations for entities could help head off some cases, he said.

No Silver Bullet for Notification Timing

Determining how quickly entities must notify affected residents about an information breach was one particular point of debate in drafting Colorado’s new law.

The original bill required notification within seven days of a breach’s occurrence, not its discovery. But Rep. Cole Wist, one of the bill’s sponsors, told Law Week in May he was willing to compromise on that part of the bill. The final bill requires notification within 30 days from the date of discovery. The 30-day window is still the shortest timeframe of any of the 50 states. Most states with time requirements allow 45 days, though more than half of states’ laws do not set forth a specific time window. Florida’s breach notification law has a 30-day window, but with the possibility of a 15-day extension.

Discovering a breach immediately creates a long to-do list for entities before they notify affected residents or consumers. But because each breach varies from the next, there isn’t one notification time window that perfectly balances the needs of affected people with realistic expectations for entities.

In some instances, Stauss said, the scope and consequences of a breach are easily apparent, such as an email phishing scam that asks employees for tax documents. In such a situation with moving pieces that are more easily determined, as quick a notification as possible to residents is best. But other situations require more time to determine a breach’s scope and impact and draft a response plan.

“A lot of thought went into … is [the time window] a reasonable compromise?” Stauss said, adding some members of Colorado’s legislature believed 30 days is too long.

Husch Blackwell partner Erik Dullea said because entities have the burden of promptly investigating breaches, it’s possible litigation will hash out whether entities that met the 30-day notification requirement still did not notify residents fast enough given each particular situation’s circumstances.

Balancing with National Standards for Best Practices

Currently no federal law governs businesses across all sectors concerning general security of consumer information. But a few statutes cover businesses in specific industries, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act governing health records and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act covering financial institutions. According to Coffman’s guidance, entities currently covered by those laws will largely be in compliance with Colorado’s new law also.

But requiring notice to the attorney general of breaches affecting more than 500 residents is an additional facet for entities to comply with. The 30-day notification window also preempts longer timeframes that other statutes may allow, such as HIPAA’s 60-day allowance.

“That is going to make a lot of companies uncomfortable … who now all of a sudden have a tighter time frame within which to notify Colorado residents whose information was potentially breached,” said Annie Harrington, a principal at Squire Patton Boggs.

But outside of the time requirement, she said HIPAA can provide guidance for an application framework of a reasonableness standard for security measures even to companies not covered by the statute because of its detailed nature.

Dullea said he finds Colorado’s new statute interesting particularly because of its requirement for entities to have a policy of destroying records containing personal identifying information they no longer need.

The provision requires a shift in mindset away from simply holding onto troves of information out of convenience. Entities having a consistent practice of getting rid of unneeded information could also help them head off accusations of destroying sensitive information if a scandal surfaces, he added.

The new mindset should be, “Do they want to hold onto data that they don’t need?” Dullea said, adding they need to ask, “What are we holding onto and why are we holding onto it?”

— Julia Cardi