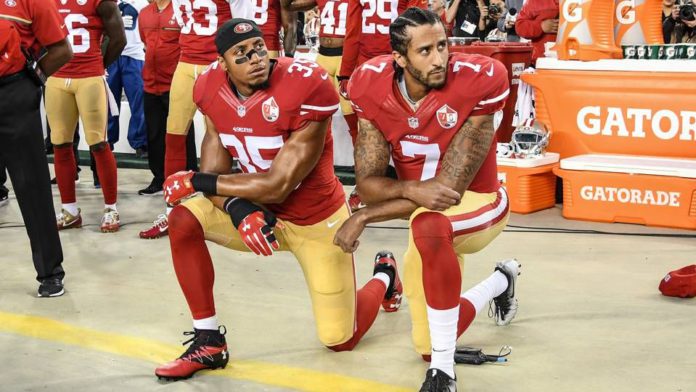

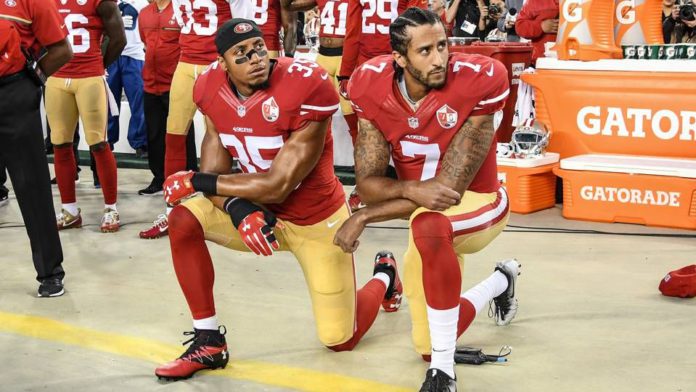

The NFL sparked the latest wave of controversy over the protests during the national anthem in May, when the league owners voted without the input of the players union to implement a new rule requiring players to either stand during the national anthem, or remain in the locker room.

Then in July, the NFL announced it would put a hold on the new rule taking effect while the league and NFLPA try coming to a compromise.

Husch Blackwell partner Thomas Godar said one aspect of the NFLPA that seems distinct from other types of unions is the sense of family players feel that encourages solidarity. The lesson to other types of unions, he said, is the need to find ways of staying relevant to their members. The need is amplified in both the public and private sectors, considering developments in each realm concerning non-union members being compelled to contribute financially to union activities.

“So when the union takes on this [player protest] issue by grieving the action of the NFL owners, they’re being relevant to their members,” Godar said. “They care how their players are being watched and responded to. That’s a big deal.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June decision in Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees overturned a 40-year precedent that had allowed public-sector unions to charge agency fees to nonmembers. Nearly 30 states have passed right-to-work laws that allow employees in the private sector to opt out of paying union fees even if they benefit from bargaining and protections the unions provide, and Missouri voters will decide on Aug. 7 whether to pass the state’s own right-to-work law.

Godar said the anthem schism raises the question of when private employers can control their employees’ use of their brand when they engage in political speech. It may be most relevant, he said, to bargaining in other sectors that involve entertainment, such as actors or screenwriters, because that it brings in the issue of where entertainers’ role as employees ends and their role as public figures kicks in.

“You couldn’t imagine that in the midst of a play, that normally one of the actors on Broadway would interrupt the play for a political speech,” he said.

But employers controlling their employees’ political speech while under their umbrella engenders a further question: How to define what constitutes political speech. Spencer Fane attorney Michael Belo, who practices labor & employment law, acknowledged the difficulty of drawing a hard line. He pointed to Justice Potter Stewart’s well-known line describing his threshold test for determining obscenity, inked into the record in the Supreme Court’s 1964 decision Jacobellis v. Ohio:

“I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.” Belo added the anthem protests in the NFL seem to clearly involve political speech since they concern perceived unjust conduct by police officers.

Godar said controlling employees’ political speech while using their employers’ brand also begs a definition of what constitutes use of the brand. NFL players protesting during games while in their uniforms seems black-and-white, but not all situations are as clear-cut: What about, Godar said, a player appearing on a talk show to promote a political platform? The player’s celebrity is still related to his role on his team, but him being outside his workplace makes it harder to define if that constitutes use of the NFL’s brand.

The National Labor Relations Act does contain some parameters protecting private employees’ speech rights. It recognizes their general right to speak about matters related to wages, benefits or other terms and conditions of employment. But Belo said the line sometimes blurs if an issue falls within those designations, but also has elements of political speech.

But the NFL’s anthem policy may not fall under the umbrella of terms and conditions of employment. Although the policy would compel players to stand during the national anthem or else remain in their team’s locker room, it did not seek to directly penalize players for noncompliance. Instead, the NFL would fine teams for their players acting against the policy. Belo speculated the league may have understood the distinction’s importance under the NLRA when the owners voted to approve the policy.

In contrast to NFL players using their celebrity status on controversial platforms, Godar used the example of Houston Texans defensive end J.J. Watt’s $37 million fundraiser for relief to Hurricane Harvey victims as a platform for using celebrity clout that few would criticize. Watt had initially set a goal to raise $200,000.

“We loved the fact that he could use his notoriety and celebrity there, but it’s quite different when it’s done at an NFL game with a stadium full of people and TV cameras on.”

—Julia Cardi