The Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers will soon attempt, for the third time since 2014, to clarify the reach of their regulatory power over U.S. waterways. The two agencies tasked with enforcing the Clean Water Act must again confront ambiguous guidance from the Supreme Court about whether the Constitution imposes any limit on Congress’ power to prevent water pollution.

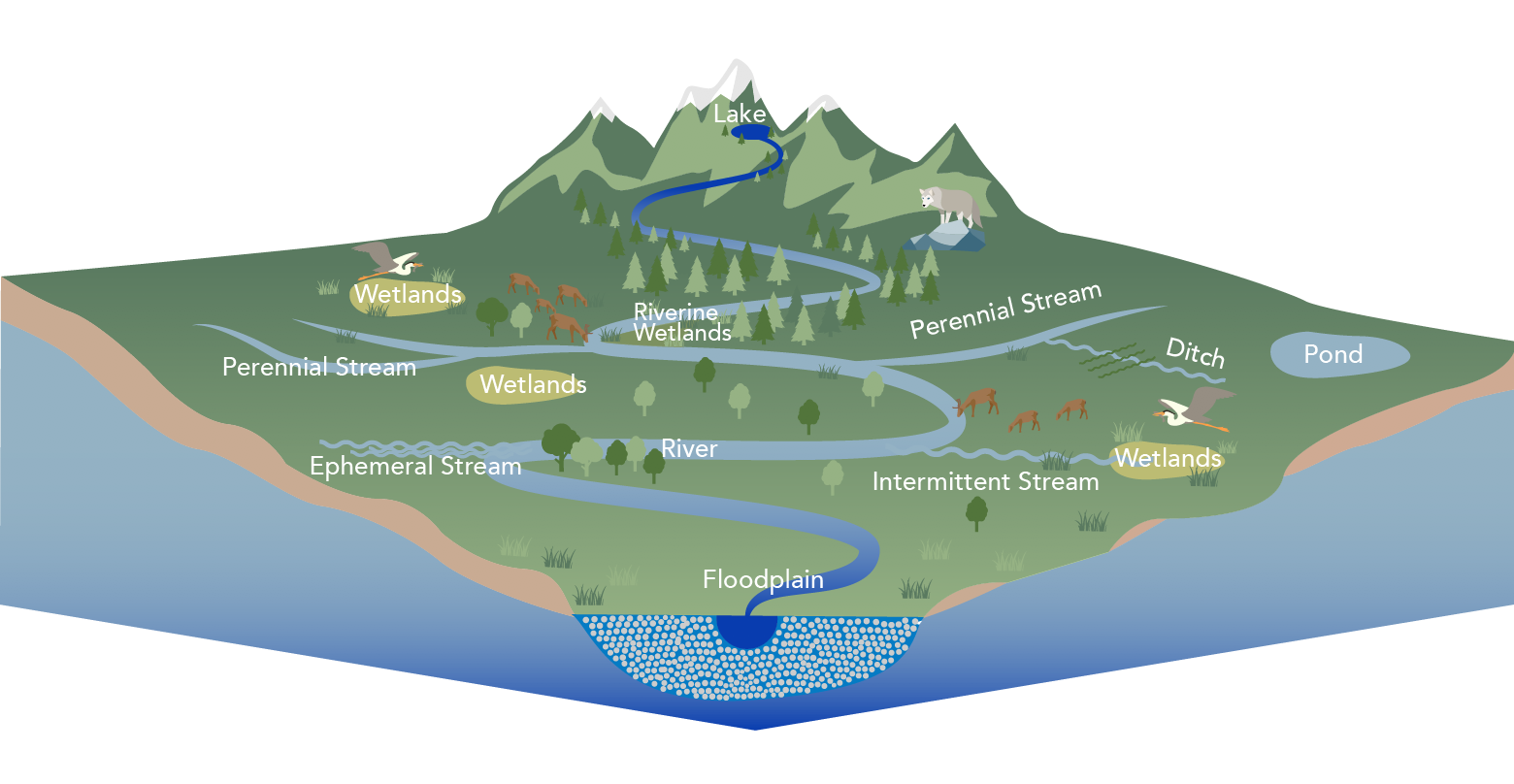

In an announcement released on June 9, EPA and the Corps said a new definition of “waters of the United States” — the statutory term that confines their authority — is needed to assure enough protection of American estuaries, lakes, rivers, streams and wetlands.

“We are committed to establishing a durable definition of ‘waters of the United States’ based on Supreme Court precedent and drawing from the lessons learned from the current and previous regulations, as well as input from a wide array of stakeholders, so we can better protect our nation’s waters, foster economic growth, and support thriving communities,” said EPA administrator Michael Regan.

The renewed effort to explicate the meaning of WOTUS, as the Clean Water Act phrase is often shortened, would replace a Trump administration rule that is barely a year old. That regulation, known as the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, is under litigation attack from states, environmental protection advocates, and Native American nations in multiple courts.

Whether any of those cases will be decided in time to provide EPA and the Corps with additional guidance about the permissible scope of WOTUS is not known. Nevertheless, Regan’s comment indicates the agency’s possible continuing uncertainty about the authorized ambit of the nation’s principal water pollution law. Two Supreme Court decisions issued in 2001 and 2006 introduced uncertainty on the point.

SWANCC and Rapanos Cause Confusion

Those opinions, in Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Rapanos v. United States, raised the question of whether the Constitution limits EPA and the Corps when they define the scope of their regulatory power under the Clean Water Act. Chief Justice William Rehnquist explained in SWANCC that the court would not read the Clean Water Act’s reach to include non-navigable waters because doing so might raise a question about whether the limits of Congress’ commerce authority were breached.

In the Rapanos case, decided five years later, Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion accused EPA and the Corps of fomenting an “immense expansion of federal regulation of land use” and subjecting “half of Alaska and an area the size of California in the lower 48 States” to control by an “enlightened despot.” He wrote that the Clean Water Act cannot afford protection to wetlands that have “only an intermittent, physically remote hydrologic connection to ‘waters of the United States.’”

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s concurrence in the 5-4 holding in Rapanos did not go so far in an effort to scale back EPA’s and the Corps’ regulatory power. Instead, he proposed a “significant nexus” test. “The connection between a non-navigable water or wetland and a navigable water may be so close, or potentially so close, that the Corps may deem the water or wetland a ‘navigable water’ under the Act,” he wrote.

Disagreements between Scalia and Kennedy formed the pillars of the two later attempts to define “waters of the United States” in a manner that could withstand Supreme Court scrutiny. The Obama administration was the first to attempt an effort to satisfy the justices.

In 2015, the agencies finalized the Clean Water Rule, a regulation that specifically said that EPA and the Corps would follow Kennedy’s “significant nexus” test. “An important element of the agencies’ interpretation of the CWA is the significant nexus standard,” it declared. “The analysis used by the agencies has been supported by all nine of the United States Courts of Appeals that have considered the issue.”

The Obama-era WOTUS rule would have reached about 60% of American waters, covering — in addition to traditional navigable waters — “those waters that science tells us provide chemical, physical, or biological functions to downstream waters and that meet the significant nexus standard.” It also excluded “erosional features, including gullies, rills, and ephemeral features such as ephemeral streams that do not have a bed and banks and ordinary high water mark.”

Many environmentalists lauded the rule. Margie Alt, then the executive director of Environment America and now campaign director at the Climate Action Campaign, told The New York Times that it was “the biggest victory for clean water in a decade,” while the Natural Resources Defense Council celebrated a regulation it saw as “an essential and commonsense reform to protect critical waters.”

Agriculture lobbyists, meanwhile, knocked the Obama rule for overly burdening farmers. “The 2015 rule provides none of the clarity and certainty it promised,” proclaimed the American Farm Bureau Federation. “Instead, it creates confusion and risk by giving the agencies almost unlimited authority to regulate, at their discretion, any low spot where rainwater collects…”

Property rights advocates, meanwhile, argued that it left states too little room to regulate water pollution. “When the federal government tries to regulate every water imaginable, it doesn’t leave much room for states and local governments to address water issues,” wrote Daren Bakst, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, in a Sept. 2019 commentary

It is not clear that all states actually can also step in and fill regulatory gaps left by Washington. “The Clean Water Act preserves states’ authority to be more protective than the federal minimum,” said Jon Devine, director of federal water policy at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “But there are obvious political, resource, and in some cases, legal obstacles to doing that. Some states have laws on the books that create impediments to adopting protections that are greater than the federal minimum.”

Whatever their merits, these arguments against the Obama rule were mounted in a series of lawsuits and the rule never took effect. Instead, a federal judge blocked it from taking effect in August 2015, preventing it from being applied in 13 states, and then the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a nationwide injunction against it several weeks later. The Supreme Court later overturned that injunction on grounds that the lawsuit that sought it had been filed in the wrong court, but by then the Trump administration had been in power for over a year.

Donald Trump’s administration would take a different tack, choosing to adopt Antonin Scalia’s more restrictive view of the Clean Water Act’s scope. Part two will look at the details of the agencies’ second try at defining WOTUS, along with the environmental consequences that have followed.