Six weeks after his inauguration, President Donald Trump issued an executive order demanding that EPA and the Corps replace the Obama-era definition of “waters of the United States.” President Trump mandated that a new WOTUS regulation must focus on “promoting economic growth, minimizing regulatory uncertainty, and showing due regard for the roles of the Congress and the States under the Constitution.” He also commanded EPA and the Corps to write a new WOTUS rule “in a manner consistent with the opinion of Justice Antonin Scalia” in the Rapanos case.

In response, EPA and the Corps began an effort to replace the Obama-era WOTUS regulation. In April 2020 the agencies finalized the Navigable Waters Protection Rule. EPA and the Corps declared that NWPR was intended to set the agencies’ understanding of their authority as extending only to orthodox concepts of U.S. waters that should be regulated by federal law. “As a baseline concept, [the rule] recognizes that waters of the United States are waters within the ordinary meaning of the term, such as oceans, rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, and wetlands, and that not all waters are waters of the United States,” the rule announced.

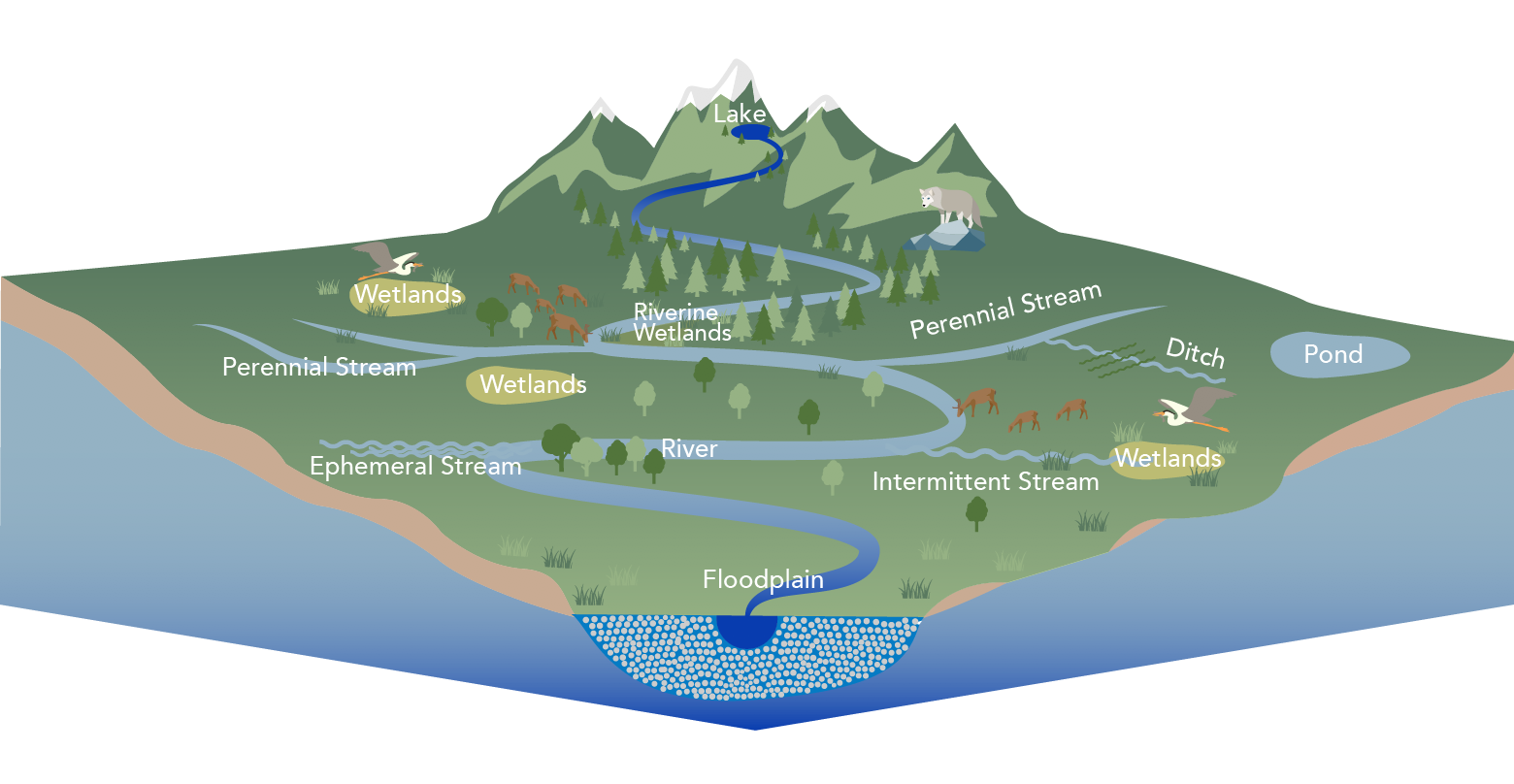

That restrictive understanding of waters of the United States left numerous waterways unprotected by federal law against discharges, dredging or filling to degradation. Those left out of the reach of the Clean Water Act for the first time since the law was enacted in 1972 included groundwater, stormwater runoff, most ditches, “prior converted cropland,” all “artificially irrigated” and most “artificial lakes and ponds,” water storage facilities “incidental to mining or construction activity,” most “stormwater control features,” the bulk of the country’s “groundwater recharge, water reuse, and wastewater recycling structures, and “waste treatment systems.”

Environmental protection advocates and scientists harshly criticized NWPR, mostly because of the waters it leaves out of the Clean Water Act’s reach. Kelly Moser, a senior attorney and director of the Clean Water Defense Initiative at the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill, N.C., said that EPA and the Corps failed to consider the goal of the Clean Water Act. “They did not consider how the changes they were making would impact the integrity of our nation’s waters,” which is the “sole objective” of the law. “It defies the law and it defies logic.”

Worse, she said, is that the proportion of U.S. waters that are now unprotected by federal law has exploded, with 92% of all waters having been found by EPA and/or the Corps to be non-jurisdictional since NWPR took effect. “The impact on our families, communities and downstream waters is potentially irreversible,” Moser said. “The fears we had have come to fruition.” She cited as one example a titanium mining project near the Okefenokee Swamp that would destroy 400 acres of wetlands and the exclusion from federal regulation of a reservoir in South Carolina that provides drinking water to hundreds of thousands of residents in Greenville.

In the arid regions of the country, the impacts have been particularly dramatic. “We have so many of our ephemeral drainages that are only active when there’s a storm event,” said Kris Randall, a former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service riparian ecologist and president of the Arizona Riparian Council. “The likelihood of something [becoming] more degraded because of activities not being regulated and occurring in an ephemeral system” is high. The lack of federal control, she said, is likely to mean that commercial and other users of streambeds will not follow best management practices. “Nobody is going to be looking at it and telling people not to do [things] in an ephemeral channel,” she said.

The Southwest’s wildlife, too, may be susceptible to harm with less oversight. “If they’re just taking out … vegetation in order to do whatever they’re looking at or doing a vegetation removal project, that can have some serious effects on animals,” Randall said. “We know our ephemeral channels are used as a transportation corridor for lots of wildlife.”

That many waterbodies in the southwest are impermanent is not consolation. “Just because a water body is temporary now or a wetland is small now doesn’t mean it will be that way in the future,” said Holly Barnard, an associate professor at CU’s Department of Geography and co-director of the university’s Hydrologic Sciences Graduate Program.

These concerns have led to at least 15 lawsuits aimed at eliminating NWPR. They include one filed by Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser in the U.S. District Court in Denver, two cases in Arizona and New Mexico that were filed by Native American nations, lawsuits in Massachusetts and South Carolina filed by environmentalists, and multi-state litigation commenced in federal court in San Francisco. Several of the disputes are moving toward resolution on the merits, including the Massachusetts and South Carolina cases. Despite the swarm of lawsuits, NWPR is in effect nationwide. The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided in April to lift an injunction Weiser obtained in 2020.

Biden’s Choice

Soon after his inauguration, President Biden commanded EPA and the Corps to try again. On Jan. 20 the president issued an executive order that repealed Trump’s directive to replace the Clean Water Rule. That led to the agencies’ June 7 announcement, in which they acknowledged who will first need to repeal NWPR in order to fulfill their professed quest to make improvements in the regulatory definition of WOTUS.

If that repeal occurs before a new WOTUS rule is finalized, water pollution regulation will be governed by definition of waters of the United States that were “in place since the early seventies, modified by guidance that relates to the SWANCC and Rapanos decisions,” said Kelly Hunter-Foster, a senior attorney at the Waterkeeper Alliance. That decades-old exegesis would be “a very protective definition,” she added.

The question is whether a federal court will vacate NWPR. The Justice Department asked a federal judge in Boston to stay proceedings in one of the lawsuits seeking invalidation of if. If the court agrees, NWPR would remain in effect until the agencies move either to repeal it or replace it with a new WOTUS rule. Moser said the environmental community is opposed to the stay request. “Every day it’s on the books, we’re losing vast amounts of critical streams and wetlands and other waters,” she said.

It’s clear the agencies will not resurrect the Clean Water Rule. Regan told a Senate committee in May that EPA “learned so much over the years” since the Obama rulemaking. At the same time, Biden will not stick with NWPR. “We’re also not quite satisfied that the waters of the U.S. rule developed under the Trump administration [are] as protective of water quality as it could be while not placing administrative burdens on our small farmers,” Regan said.

Hunter-Foster said the public should not be surprised that a third effort is needed because both the Obama- and Trump-era WOTUS definitions are flawed and because EPA and the Corps have erred by seeking to placate development interests. “Making everyone happy is not the way to find the right answer,” she said. “As the regulatory agencies granted [the] discretion, you should definitely listen to stakeholder input. You should seek it out. But you should look into what you should be basing your decision on what the objective of the Clean Water Act is.”

She remarked that the agencies’ June 7 announcement provides reason to be optimistic that Washington may come closer to the mark this time. “[T]he first bullet is protecting water resources in our communities consistent with the Clean Water Act and the second one is science,” she said. “And, you know, that’s music to my ears. That’s exactly how you should look at it.”