A federal appeals court breathed new life into a Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower retaliation claim, and the plaintiff could take it to trial eight years after his termination.

Carl Genberg, a former executive at pharmaceutical company Ceragenix, claimed he was fired in retaliation for reporting securities law violations in a pair of emails to the company’s board of directors. He also claimed the compay’s CEO, Steven Porter, defamed him in the wake of his firing. The Colorado federal district court previously granted Porter’s motion for summary judgment on both claims.

In a majority decision published Feb. 22, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court in part and allowed Genberg’s retaliation claim to move forward but affirmed the defamation claim’s demise. The 10th Circuit, by applying a broader standard of what constitutes SOX-protected activity, reopened the path to a trial presuming the case doesn’t get first get reviewed by the appeals court en banc.

“We’re very excited to have this victory and to have the opportunity to try the case,” said Clayton Wire, who argued the appeal for Genberg. He noted that the 10th Circuit majority, which applied the Sylvester v. Parexel “reasonableness” standard in this case, had done so previously but only in an unpublished opinion. “This is precedent setting,” Wire said.

Robert Reeves Anderson, a partner at Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer who argued the appeal for Porter, said he could not provide comment for this article as the litigation is still pending.

The appeals court determined that a reasonable fact finder could conclude that a critical email Genberg ghostwrote to Ceragenix’s board of directors was SOX-protected activity. In so doing, the 10th Circuit rejected the district court’s reasoning that the email didn’t grant Genberg SOX protection because it didn’t specifically refer to a SOX violation. This “definitive and specific” standard was “obsolete,” according to the appeals court. The appeals court instead applied the Sylvester standard, under which Genberg needed only to show a “reasonable belief” that the conduct he complained about was unlawful under SOX.

The email arose from a dispute between Genberg and the Ceragenix board. Both he and Porter worked for a company, Osmotics Corporation, that reverse-merged with Ceragenix in 2005. According to a distribution plan following the reverse-merger, 12 million Ceragenix shares — and the voting rights that came with them — were supposed to be distributed to the Osmotics Corporation shareholders. But five years after the merger, those shares remained in a custodial account, and Ceragenix’s board retained full control of them under the initial proxy.

Genberg tried to get another Osmotics shareholder, Joseph Salamon, involved by having him write an alternate distribution plan to submit to the Ceragenix board. Porter rebuffed the plan and expressed concern about Genberg disclosing private information to the shareholder.

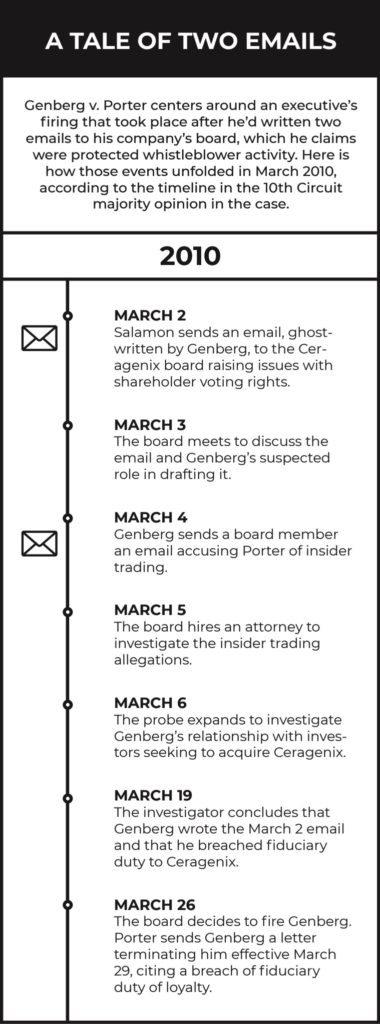

Genberg ghostwrote an email on March 2, 2010, from Salamon to the board that cited concerns about the shares and the continued reliance on the initial proxy. Porter told Genberg to cease his communications with outside shareholders on the issue. Genberg on March 3, 2010, accused Porter of insider trading and other securities violations in an email to the head of the Ceragenix audit committee.

Ceragenix launched an investigation into the insider trading claims as well as whether Genberg wrote the Salamon email. The investigation found that Genberg breached his fiduciary duty and his action was a fireable offense. Ceragenix’s board of directors voted unanimously to fire Genberg, and Porter sent him a termination letter citing breach of fiduciary duty.

Genberg claimed he was terminated as retaliation for SOX-protected activity and that Porter made defamatory statements about his firing in publications.

Senior U.S. District Judge Wiley Daniel in August 2016 granted Porter’s motion for summary judgment and dismissed Genberg’s SOX retaliation and defamation claims with prejudice. The court said the Salamon email didn’t allege a violation of a securities law and that “general inquiries do not constitute protected activity.” The fact that Genberg was a securities lawyer, yet he didn’t refer to a specific statutory violation that he’d likely know of, carried weight in the district court decision.

“[Genberg’s] knowledge of SOX and related matters, along with the nonspecific allegations of his email, lead the Court to conclude that he did not have a reasonable belief that any specific SEC rule or regulation was being violated,” according to the summary judgment order.

The 10th Circuit differed. “But a factfinder might reasonably conclude that there was little need for Mr. Genberg to name the rule, for it seems to clearly bar use of a proxy for shareholder votes after the next annual meeting,” according to the 10th Circuit majority opinion penned by Judge Robert Bacharach.

The alleged SOX violations in the ghostwritten Salaman email, according to the appeals court, might be its complaints that the Ceragenix board held onto its initial proxy for “years longer than was ever contemplated” and that it “deprived [the Osmotics shareholders] of any voice in the management of Ceragenix.” Genberg said under oath that he believed the board was violating SEC Rule 14, and Porter disputed that statement, but that’s a matter that can’t be resolved on summary judgment, the 10th Circuit held.

10th Circuit Judge Harris Hartz dissented from the summary judgment reversal on the retaliation claim. He supported the district court’s finding “that no reasonable juror could infer” that Genberg believed the Salamon email reported a securities law violation. Similar to the district court, Hartz appeared to find the email’s lack of reference to SOX puzzling in light of Genberg’s legal background.

“I can think of no better way to encourage the directors to comply with a request than to say that what is being requested is commanded by federal securities law. But the email never says that,” Hartz wrote.

Although the retaliation claims proceed, the 10th Circuit kept the door shut on Genberg’s defamation claims, which allegedly arose from several statements Porter made.

Following Genberg’s termination, Porter issued statements to a Ceragenix public relations consultant, saying Genberg attempted a “hostile takeover assault,” acting as “the Judas in house facilitating [the] takeover.” Ceragenix also issued a notification to the Securities and Exchange Commission reporting that it had terminated Genberg for cause. Additionally, Porter emailed Ceragenix lenders telling them Genberg was fired for “willful breach of fiduciary loyalty.” Genberg claimed that each of these constituted defamatory statements.

But the 10th Circuit decided the defamation claims failed under Nevada law because Genberg didn’t show evidence that Porter thought the disparaging statements he made were false.

While the parties might prepare for trial on the surviving retaliation claim, the defense might also weigh an en banc rehearing. Seeing the division in the panel decision, there could be viability to putting the retaliation claim before the full 10th Circuit.

— Doug Chartier