Legal practice can be stressful enough on its own, but for family attorneys and others who regularly deal in traumatic situations, it can take a heavier emotional toll over time. Being adjacent to so many emotionally-charged events — from child abuse and domestic violence to the custody disputes themselves — family attorneys run a relatively high risk of developing secondary traumatic stress.

Although it can be difficult to pinpoint, secondary traumatic stress is preventable and treatable with good law practice habits and self-care, even in a legal area as crisis-prone as family law.

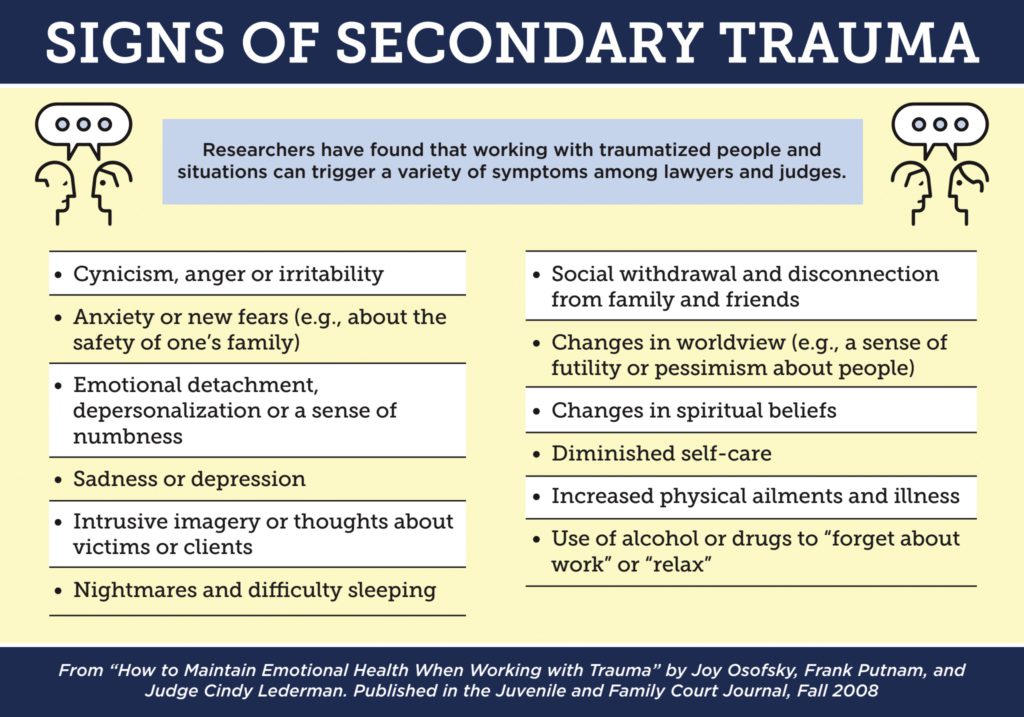

Secondary traumatic stress, which is sometimes also referred to as compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma, is a condition that can occur in someone who is exposed to or hears about traumatic experiences that happen to others. A person suffering from secondary trauma will often experience symptoms like chronic nightmares and anxiety and sometimes turn to substance abuse, much like someone with post-traumatic stress, except without a traumatic event actually happening to them.

While the phenomenon is a widely recognized occupational hazard of the mental health profession and social work, attorneys are often just as susceptible to secondary traumatic stress — if not more so.

Family lawyers (along with criminal defenders) showed higher levels of secondary trauma responses than even social workers and mental health professionals, according to a 2003 survey by Andrew Levin and Scott Greisberg. The researchers attributed that difference to the lawyers’ “lack of supervision” of the traumatic effects they were exhibiting and their higher caseloads.

The physiological dynamics that underlie secondary trauma are complicated, but the general idea is simple — the nervous system is negatively responding to someone else’s traumatic event.

People who suffer from secondary trauma can experience the same symptoms as someone who suffers from PTSD, including changes in sleeping patterns, a darkening worldview and fluctuations in appetite resulting in unintentional weight gain or loss. But what can also make secondary trauma trickier to identify than PTSD is that it builds up over time as opposed to emerging from a specific event, according to Sarah Myers, executive director of the Colorado Lawyer Assistance Program.

“Generally speaking, secondary trauma isn’t going to occur from hearing one story,” Myers said. “It’s after you’ve heard 20 or 30 of these stories.” Family attorneys are repeatedly exposed to situations where parties treat each other cruelly or inflict distress and harm on children in the cases, and those exposures have a cumulative effect on attorneys’ mental wellbeing, she said.

Compassion fatigue and “burnout,” both of which can result from untreated secondary trauma, present with additional symptoms, such as exhaustion and feelings of resentment and contempt for “needy” people, she added.

COLAP is a confidential, independent program that helps lawyers, judges and law students with both professional and personal concerns, including stress management, emotional health and substance use issues. When an attorney suffering from secondary trauma comes to COLAP, it might be someone who says he or she has “held it together for so long” after decades of practice and is only recently showing signs of distress or experiencing emotional problems, Myers said.

Symptoms of secondary trauma can manifest both in and outside the lawyer’s work, from avoiding calls and emails from stress-inducing clients to crying at inappropriate times.

It can also lead to broad changes in behavior. Attorneys who used to be outgoing become shut-ins. Normally well-kempt lawyers start to abandon their grooming and hygiene habits. “Basic changes in the way that we respond to the world are usually a good marker that something is going on,” Myers said.

Colleagues, spouses and friends will often notice when those behavioral changes are occurring, and attorneys should pay attention when others mention those changes they’re seeing, Myers said.

EMPATHY VS. COMPASSION

Kelly Lynch Murphy, a partner at The Harris Law Firm’s office in Evergreen, said that she and other lawyers at her family law firm are conscious of when a new case will involve traumatized individuals or traumatic situations.

“It’s always a factor that we evaluate and consider as soon as we meet the client for the first time,” Murphy said. But secondary trauma “is not discussed as much as it should be” across the state’s family law bar, she said. Granted, the bar does try to address wellness in general, and there are different support groups and resources that assist attorneys with mental health issues, she noted.

Erika Holmes, a Denver-based solo family attorney, said family lawyers don’t talk enough about secondary trauma as it affects their personal lives. Although they’re eager to vent to each other about the cases and work situations that are stressing them, it’s much less common that they’ll say to each other, “‘This case is really bothering me,’ or ‘I can’t let this one go,’” she said.

The problem that many family attorneys have, Holmes said, is they think they have to take on their clients’ emotions to be a good lawyer. She prefers a “low-drama” approach to her cases; despite the fact she’s also a contract attorney with Project Safeguard and regularly works with protection order seekers, she doesn’t take their stresses home with her, she said. “I tell my clients, ‘It’s your job to be emotional, it’s my job to be rational.’ ”

Family attorneys can put themselves at greater risk of secondary trauma when they willingly absorb their clients’ stress as a means to be “empathetic,” believing it necessary to properly advocate for clients. But there’s a difference between empathy and compassion, Myers said: “Empathy is taking on someone else’s stress as your own,” but compassion is understanding the stress the other person is feeling, which doesn’t require internalizing it.

Murphy said she deliberately keeps an emotional distance from her cases, not just for her own sake but also to be a more effective lawyer and capture more of the case’s details. “It’s important to remember that as the attorney you have to see all of the elements and arguments on the issue,” she said. “I always remember that if I get [emotionally] involved, I’m missing elements.”

WAYS TO COPE

Myers said that if attorneys think they might be suffering from secondary trauma, compassion fatigue or burnout, they can reach out to COLAP, which provides confidential life coaching and refers clients to mental health or addiction specialists as needed. What is also helpful is to talk to trusted peers about how their cases are affecting them, which helps normalize their circumstances — and chances are those peers can relate. “If you talk to trusted colleagues, 9 times out of 10 they’ll say, ‘I totally understand what you’re going through,’ ” Myers said.

A bulwark against secondary trauma, Myers said, is to “create routines … to help demonstrate the separations in your work and your personal life.” Those routines can be as simple as listening to classical music only on the evening commute, or going for a walk immediately after arriving home. These types of behaviors cue the nervous system that the workday is over and that its residual emotions shouldn’t persist.

“There has to be a sort of separation [between work and personal life] or else the nervous system doesn’t understand that there is one,” Myers said.

Murphy’s go-to’s for self-care usually involve going for runs and activities with her family. On the client side, she said she sets clear expectations on when she will or won’t be reachable, and she never gives clients her cell phone or personal email.

Especially in family law, with its exposure to clients’ emotionally charged stories, “self-care is extremely important, not only for taking care of you but also for taking care of your clients,” Holmes said. Otherwise the attorney is liable to take frustrations out on clients, she added. Holmes runs, meditates, and rides a bike, often in the middle of the day when she can. She makes a point of taking care of personal errands like grocery shopping early in the day so she can focus on work second. She likens it to how you’re supposed to put on your oxygen mask during an emergency on an airplane before trying to help someone else with theirs.

However attorneys prefer to combat the creep of secondary trauma, it might just be part of the job. For family lawyers to suffer adverse effects from their trauma-inflected caseload is normal, Myers said, adding that attorneys should recognize that they are “not going to be immune to this level of stress and trauma.”

— Doug Chartier