After a 16 year-battle to preserve federal water transfer rules, Western states and water providers can finally rejoice. Late last month, the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari in a case involving several states and districts on water transfers, reaffirming a 2nd Circuit opinion from 2017 that excludes those transfers from pollutant permits under the Clean Water Act.

“We had not won anywhere along the line until we got to the 2nd Circuit, and there we won with a divided court,” Berg Hill Greenleaf Ruscitti partner Peter Nichols said. “Having the Supreme Court let that decision stand was a huge relief. It meant we finally achieved what we set out to achieve.” Nichols has served as lead counsel for the Western water providers throughout litigation.

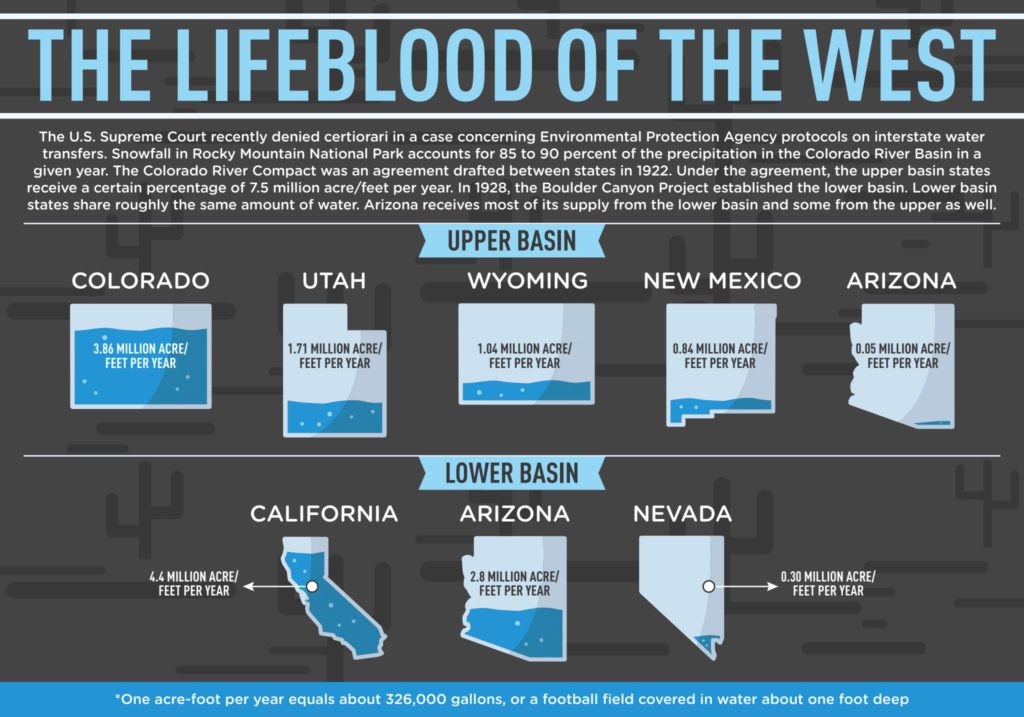

Water transfers are exactly what they sound like — a transfer of water from one river basin to another to supplement shortages. Thousands of water transfers occur throughout the country every day, and through 50 major transmountain diversions and roughly 1,700 smaller transfers throughout the state, the Colorado River Basin supplies more than 50 million people in several states with water.

The Clean Water Act outlines a permit program called the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. The act prohibits anyone from emitting pollutants without a permit, which limits what can be discharged and sets forth other requirements to ensure water quality and public health. The language is broad; it states that if one “discharge[s] from a point source into the waters of the United States,” a permit is required. But Nichols said prior to adopting the rule, the EPA had never really regulated water transfers the same way it did water emissions from things like mines or sewage plants.

The case, Catskill Mountains Chapter of Trout Unlimited, Inc. v. Environmental Protection Agency, stretches back to a 2004 case filed by the Miccosukee Tribe against the South Florida Water Management District. That case went up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which noted that the EPA didn’t have an official position on the application of NPDES permits to water transfers and invited the agency to create one. Nichols said water transfer exclusion from the permits was the “status quo,” but the rule wasn’t formal. In 2008, the EPA issued its official rule that water transfers are not subject to the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permitting program.

When water is transferred from one basin to the next, it naturally picks up “pollutants” as it flows through tunnels and canals that may have a different mineral composition than where it originated. CWA language that defines pollutant is also vague and can include any “industrial, municipal and agricultural waste discharged into water.”

“During spring runoff, erosion puts a lot of sediment into the canals and it gets transferred into water that may not have that same level of sediment,” Nichols said. “You’d be required as the transferor to meet all the water quality standards of the receiving water body, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. It would be technologically and economically infeasible to do it.” The 2nd Circuit found that some financial estimates for compliance on just the major water transfers in the West would cost upwards of $4 billion.

After the 2008 rule was implemented, 11 states led by New York — along with several environmental groups, the province of Manitoba and tribal governments — sued the EPA. The case was consolidated in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. Ten Western states including Colorado and 26 water providers throughout those states jumped into the fray as defendants, but the 11th Circuit denied the intervention. Later, the 11th Circuit ruled it did not have jurisdiction, and a U.S. Supreme Court ruling stated that jurisdiction belonged to federal district courts.

After the 11th Circuit lifted its stay, the cases in the Southern Districts of New York and Florida were reactivated and the Western defendants intervened.

The district court found that the water transfer rule was an “unreasonable interpretation” of the CWA. Defendants argued that the ruling overrides a longstanding deference to the states on water allocation and management. They appealed, and the 2nd Circuit reversed the district court ruling in a split opinion. The majority found the water transfer rule “represents a reasonable policy choice,” and applied the “Chevron Test” which was developed after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council. The test determines whether to grant deference to an agency’s statute interpretation.

But 2nd Circuit Judge Denny Chin dissented, arguing that the exclusion of transfers from the permit rules is counterintuitive to the purpose of the CWA.

“Clean drinking water is a precious resource, and Congress painstakingly created an elaborate permitting system to protect it. Deference has its limits; I would not defer to an agency interpretation that threatens to undermine that entire system,” Chin wrote in his opinion.

Nichols said it was “no accident” that challengers of the rule were all Eastern states where water is plentiful. Colorado’s snowpack this year is only at about 60 percent of what it should be as the West continues to struggle with resource management. Nichols said the ruling removes a great deal of uncertainty for Western states and water providers “as we struggle to deal with population growth, climate change and drought. People can now focus more on that and not worry about what could’ve happened here.”

—Kaley LaQuea