Attorneys at Keating Wagner Polidori Free have secured a significant amount of damages in a case representing wastewater treatment systems company WSI International for claims that former employees benefitted from the unauthorized use of WSI’s trade secrets.

One victory came through arbitration because of defendants Yuan Xu and Guichun Zhang’s employment agreements, and the Arapahoe County District Court handed down a judgment against defendants Michael Fields and Orion Water Technologies, a company Fields, Xu and Zhang formed. Several other companies formed by the three were also named as defendants, including Evergreen Global Environmental and Bioenergy Recovery Technologies.

The district court and arbitrator awarded damages largely for unjust enrichment because of financial benefits the defendants gained through the use of WSI’s trade secrets. The court and arbitrator also awarded damages for the defendants’ breach of fiduciary duty to WSI, using their salaries as a basis for calculation. The court also awarded attorney fees, costs and prejudgment interest to WSI.

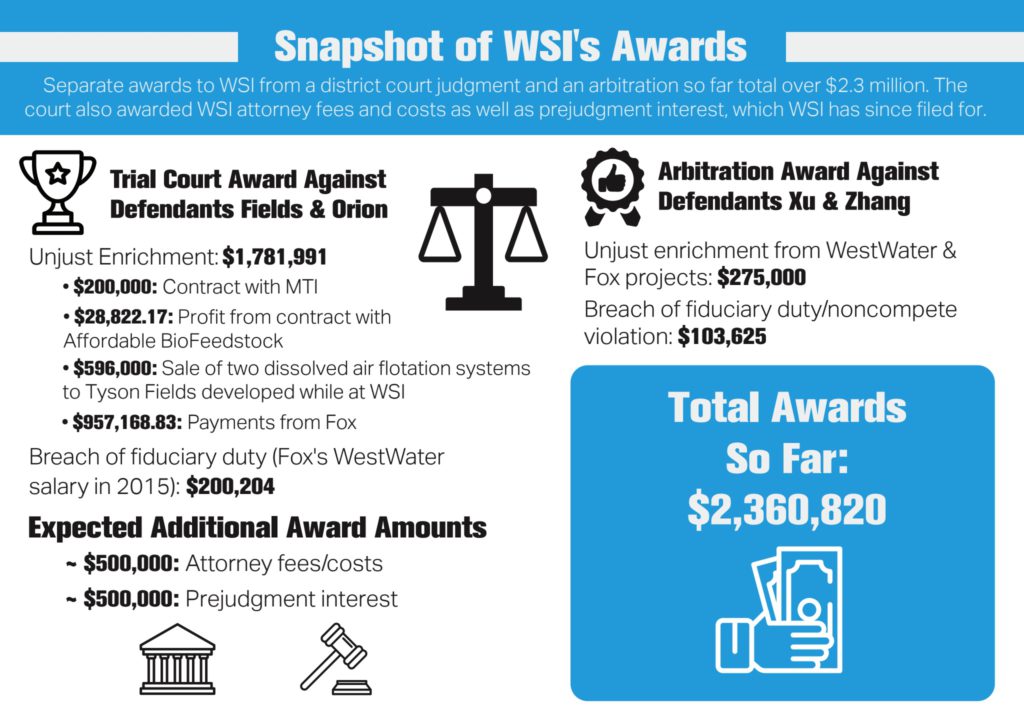

The damages determined so far by the court and arbitrator total $2,360,820 for unjust enrichment and breach of fiduciary duty. Plaintiffs’ attorney Daniel Wartell said the fees, costs and interest they have filed for should total about another $1 million. Xu, Zhang, Orion and Fields were found joint and severally liable for the damages awarded.

Lidiana Rios of Keating Wagner also represented WSI in the case.

CASE BACKGROUND AND FINDINGS

The Uniform Trade Secrets Act, which Colorado has adopted, defines a trade secret as “the whole or any portion or phase of any scientific or technical information, design, process, procedure, formula, improvement, confidential business or financial information, listing of names, addresses, or telephone number or other information relating to any business or profession which is secret and of value.”

In other words, it’s something of value that would give competitors an advantage that a company takes steps to keep confidential from the public domain. The act also allows five possible types of damages for plaintiffs resulting from misappropriation of trade secrets, including actual losses, the amount of unjust enrichment or disgorgement of profit (computed separately from actual losses), royalties, exemplary damages, and attorney fees and costs for the prevailing party.

WSI’s vault of work product, altogether about 850 gigabytes of data, included project files, designs, bid and cost spreadsheets, contracts, project-specific marketing materials, client-specific drawings, marketing methods and formulas and data compilations. WSI protected the vault with a firewall, password and requirement for a digital access certificate.

Despite the definition, Wartell said attempting to prove something a company possesses is actually a trade secret often presents a challenge. An example could be a client list that could technically be considered public information because anyone could look up those on the list. But compilation of otherwise publicly available information could constitute a trade secret, Wartell said, because of the significant time investment required.

The district court found WSI’s vault of information took significant time, effort and resources to develop. The court also noted that testimony revealed the information would have been useful for any business in wastewater treatment plant bidding, design or construction that either competed with WSI or was starting services that would compete with WSI in the future.

Fields founded WSI, which designs, engineers, manufactures, and sells wastewater treatment systems and sells industrial and agricultural equipment. After he transferred his ownership interest to Allie Tyler in 2013 or 2014, Fields served as an employee and the company’s president. Xu and Zhang worked for WSI as engineers designing and developing the treatment systems. All three stopped working for WSI in May 2016.

After WSI began experiencing significant financial difficulties in 2014, Fields accepted employment with WestWater, another company that designs and sells wastewater treatment facilities. While still employed with WSI, Fields received benefits and a monthly salary from WestWater. Kirk Shiner, a WestWater representative, testified the company considered it beneficial for them to have Fields continue working for WSI because he played an integral role in developing and promoting technology.

The district court stated there was no evidence that WSI knew about, approved of or otherwise gave permission for Fields receiving a salary from WestWater while still employed by WSI.

In December 2016, WSI obtained a preliminary injunction against the defendants, in which they claimed they no longer possessed WSI’s proprietary, confidential information and trade secrets and that they would not use or disseminate it until further orders from the court.

But evidence showed Fields, Xu and Zhang had lied when they said they had gotten rid of the information they had taken belonging to WSI, and in fact still possessed the company’s trade secrets. WSI brought in a computer forensic examiner, who found the defendants had run a drive cleaner before turning over their computers, but they had not successfully wiped away all the information. As a result, an appointed special master judge found the defendants had violated Colorado’s Rules of Civil Procedure and case management order, and recommended an award of attorney fees and costs against the defendants.

In addition to Fields receiving a salary from WestWater, he formed a handful of companies along with Zu and Zhang including Orion, Evergreen and Bioenergy. Through these companies, Fields, Xu and Zhang engaged with customers in sales and business contracts that poached business and profits from WSI. The trial court and arbitrator found the defendants had benefitted from WSI’s vault of trade secrets that they retained copies of after they stopped working for WSI.

The district court found Fields had breached his fiduciary duty to WSI by accepting a salary from WestWater and taking business contracts from WSI through the companies he had set up with Xu and Zhang. For the breach of duty, the court awarded WSI $200,204 in damages, which equaled Fields’ salary from WestWater in 2015.

The arbitrator also awarded damages to WSI for breach of fiduciary duty by Xu and Zhang, as well as for violation of non-compete agreements in their employment contracts. Those damages totaled $103,625. Damages for WSI awarded by the district court and arbitrator for unjust enrichment of the defendants through business they took from WSI totaled $2,056,990.83.

“Defendants have no right to possess or use WSI’s confidential and proprietary information and trade secrets, and suffer no harm by being prohibited from using them,” wrote Weishaupl in ordering a permanent injunction against the defendants. “This private dispute does not invoke a specific public interest, but generally, protecting a person or entity’s trade secrets encourages innovation in the market, promotes healthy competition, and prevents competitors from gaining an unfair advantage by using the fruits of another’s labor.”

Wartell expressed a similar sentiment, and said trade secret law is interesting because it affects all types and is quite apolitical. He has represented businesses ranging from small startups to Fortune 500 companies, who all have a common interest in protecting their investments.

“If there weren’t these protections in place, it would create a really hostile environment toward innovation,” he said. “If there’s no way to protect your secret and you can’t give your key employees access to information without fear that they’re going to take it to some competitor and profit off of it, it would really slow the wheels of innovation a lot.”

—Julia Cardi