The U.S. Supreme Court on June 4 issued a narrow, much-anticipated ruling in favor of baker Jack Phillips in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court found the commission violated Phillips’ constitutional protection of religious liberty when it ruled Phillips had violated the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act.

The Civil Rights Commission’s treatment of Phillips’ case “showed elements of a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs motivating his objection,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy in the majority opinion. In the days since the decision, groups on each side have given their own spin to the decision to color it as advantageous: LGBTQ rights groups touting its narrow scope and limited applicability, and supporters of Phillips’ position trumpeting the decision as a victory for religious freedom.

But ultimately, the decision is a narrow one that doesn’t affect the substance or enforcement of CADA. From a practical perspective, the ruling left the First Amendment and LGBTQ merits wide open for future cases, and the judicial minimalism reflected in the decision has become a hallmark of the Roberts Court.

“Just because the case makes it to the Supreme Court doesn’t mean it’s the perfect vehicle to get an answer for a question, and I think they recognize that here,” said Micah Dawson, an associate at Fisher Phillips who practices employment law. “They’re challenging the legal community to bring them the better question or present it in the right way.”

The case dates back to 2012, when, because of religious objections to same-sex marriage, Phillips declined to create a wedding cake for David Mullins and Charlie Craig, who planned to marry in Massachusetts. Phillips claimed that First Amendment protections for religious freedom and freedom of expression overrode the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act, which prohibits businesses open to the public from discriminating based on sexual orientation.

Mullins and Craig filed discrimination charges, and several lower courts have ruled against Masterpiece Cakeshop since 2012. In 2013, Administrative Law Judge Robert Spencer decided Masterpiece Cakeshop could not receive a religious exemption from the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission made the same ruling in 2014, and the state appeals court affirmed the decision in 2015. In 2016, the Colorado Supreme Court declined to review the case. The U.S. Supreme Court first agreed to hear the case last summer.

Kennedy wrote the findings of hostility showed through in endorsements by commission members at its public hearing in the case that religious beliefs cannot legitimately carry over into the public or commercial sphere and disparagements of Phillips’ religious beliefs. He also took issue with the commission’s disparate treatment of Phillips from other bakers who had refused to make a particular customer a cake with anti-gay messages, which the commission decided had acted lawfully.

Novel to Phillips’ case, for example, was the commission’s theory that any message on the wedding cake would be associated with the customer, not the baker.

“For these reasons, the Commission’s treatment of Phillips’ case violated the State’s duty under the First Amendment not to base laws or regulations on hostility to a religion or religious viewpoint,” Kennedy wrote. “The government, consistent with the Constitution’s guarantee of free exercise, cannot impose regulations that are hostile to the religious beliefs of affected citizens and cannot act in a manner that passes judgment upon or presupposes the illegitimacy of religious beliefs and practices.”

Craig Konnoth, an associate law professor at the University of Colorado Boulder who attended the case’s oral arguments in December, said the case’s friction between LGBTQ rights and the scope of anti-discrimination policies is not new. Writing a separate majority opinion in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez, Kennedy punted on a question of whether a purportedly neutral policy at Hastings College of the Law requiring student groups to accept all students unfairly benefitted pro-LGBTQ groups. Konnoth said while Kennedy may be starting to realize the boundaries of free speech as protection for LGBTQ rights finds increasing success in courts, he could be hesitant to limit what he has historically been a staunch defender of.

“I think he’s reluctant to take away with one hand what he has just given with another,” Konnoth said.

Steven Collis, a partner at Holland & Hart who chairs the firm’s First Amendment practice group, said he doesn’t like the characterization by some that the Supreme Court didn’t reach the case’s merits. First Amendment analysis under the Free Exercise Clause requires asking whether or not a law or regulation is neutral or is being applied in a neutral manner.

“That’s the merits, and they got to that question on the merits,” he said. The court looked at the Civil Rights Commission’s enforcement of CADA under the Free Exercise Clause and decided it wasn’t neutral, he said, “and in this particular case, there was really no reason to trouble the free speech waters or to trouble the other portions of the Exercise Clause or even get into the Establishment Clause part of it, which they could have done if they’d wanted to.”

Dawson said Chief Justice John Roberts’ tendency to push for narrow rulings to build consensus among the justices likely had a lot of influence on this decision’s scope. Roberts recognizes that applying a limiting principle in highly fact-specific cases makes room for better discourse on other cases that have real potential to effect legal change, he said. Using the wrong case to set a sweeping precedent carries the danger of lower circuit courts clashing for years over how to interpret it.

“He’s a historian of the court, and I think he recognizes how he wants his decisions to be seen in 50 years.”

Konnoth speculated the court could have made an equally narrow decision in favor of the couple, based on a lack of any discussion between them and Phillips about the cake’s design before Phillips objected to making them a wedding cake.

The court could have ruled “given that there was no discussion even of the product, it was simply the appearance of the couple that caused the baker to object because he realized they were a same-sex couple, that that’s a problem,” he said. It’s still unclear in those circumstances, Konnoth added, whether the cake would have constituted artistic expression.

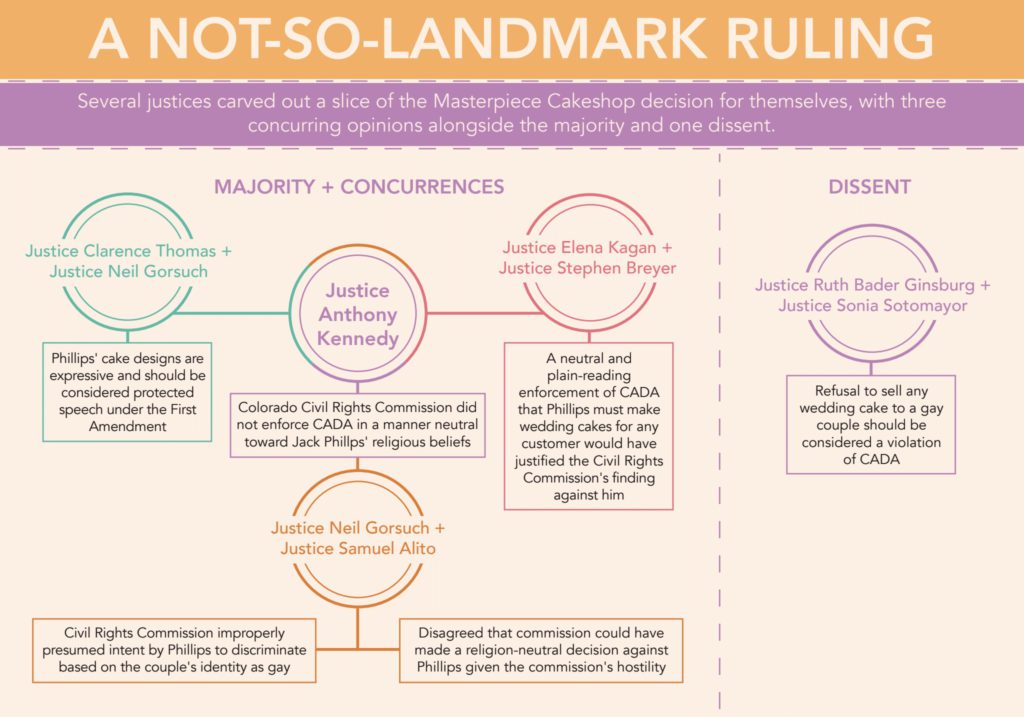

Justice Elena Kagan filed a separate concurring opinion, which Justice Stephen Breyer joined, and Justice Neil Gorsuch filed another concurring opinion joined by Justice Samuel Alito. Justice Clarence Thomas filed a third concurrence that Gorsuch joined. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

Each concurrence elaborated on a different facet of Kennedy’s majority opinion. Kagan wrote that a neutral and plain-reading enforcement of CADA that if Phillips makes wedding cakes for heterosexual couples, he must make wedding cakes for any couple, would have justified the Civil Rights Commission’s finding against him. Gorsuch disagreed with that position, opining the commission wouldn’t have been able to make a religion-neutral decision against Phillips given the case’s facts. The Civil Rights Commission, Gorsuch argued, improperly presumed intent by Phillips to discriminate based on the couple’s identity as gay.

Thomas’ concurrence addressed the issue of free speech that Kennedy’s opinion did not reach, arguing Phillips’ cake creations should constitute expression protected by the First Amendment.

In dissenting, Ginsburg wrote that a refusal to sell any wedding cake to a gay couple should constitute a violation of CADA.

Collis said the heavily weighted majority seems to send a few messages. It seems to be a rebuke of some commissioners’ comparison of Phillips’ religious beliefs to those used to justify historical events such as slavery and the Holocaust.

Thomas’ concurring opinion provided an indirect repudiation of the comparison. In arguing Phillips’ cake creations should be considered protected expression by the First Amendment, he wrote it is “hard to see how Phillips’ statement is worse than the racist, demeaning, and even threatening speech toward blacks that this Court has tolerated in previous decisions. Concerns about ‘dignity’ and ‘stigma’ did not carry the day” in previous decisions, Thomas wrote, when the court affirmed as protected forms of expression the rights of white supremacists to burn a cross, conduct a rally on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, and circulate a film featuring Ku Klux Klan members making threatening statements using slurs.

The 7-2 ruling seems to also implicitly send the message, Collis said, that opposing interest groups are better off finding compromises themselves to the issues presented in the case, such as legislative solutions, instead of making the Supreme Court decide. Because the Supreme Court only ruled on the neutrality of the Civil Right’s Commission’s enforcement of CADA, it did not show its hand on how it might rule on the aspects implicating the First Amendment or the substance of CADA itself.

“Both sides, I think, would be concerned that if they take another case up there they really can’t predict whether or not they’re going to win,” Collis said. “And I wonder if part of what the court was doing here was trying to send the signal that both of you could lose and you can lose badly, and so you’re you’re better off trying to find legislative compromises and other compromises rather than continuing to bring it to us.”

—Julia Cardi