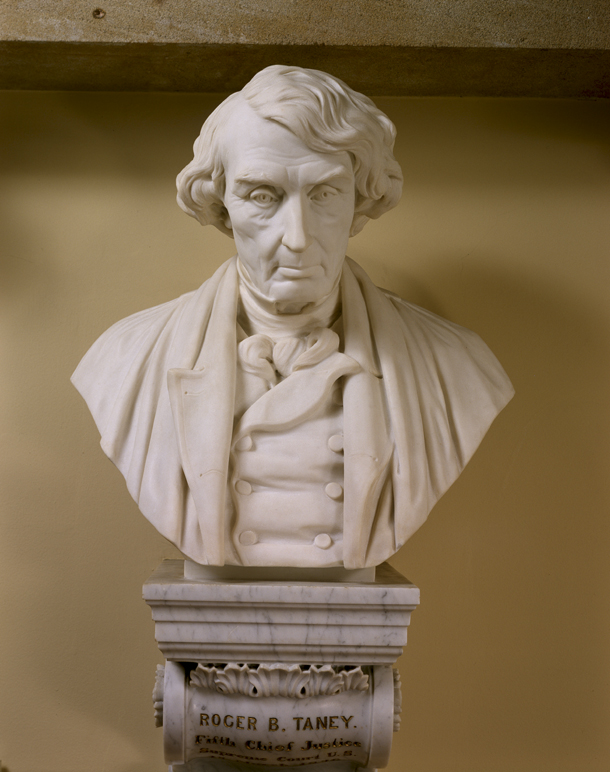

The House of Representatives voted Tuesday evening to remove from the Capitol’s public areas a bust of Chief Justice Roger Taney, the antebellum period jurist who wrote a Supreme Court decision denying even freed Black Americans any prospect of citizenship and that was a principal immediate driver of the Civil War.

The House’s action, if adopted by the Senate and signed by President Joe Biden, would also eliminate from public view any statues in the Capitol that honor Confederate leaders and rebel soldiers and sailors, along with secessionist or white supremacist politicians from the eras both before and after the 19th century War of the Rebellion.

“It is long past time to remove from a place of honor in our nation’s Capitol the statues and busts of those who favored war against the United States in support of a so-called government founded on a cornerstone of racism and white supremacy,” said California Democratic U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren, chairman of the House Administration Committee, during floor debate on the bill.

The chamber’s GOP members mostly opposed the measure. Minority leader Kevin McCarthy of California attempted to discredit it by arguing that the Democratic Party is racist. “Democrats are desperate to pretend their party has progressed from their days of supporting slavery, pushing Jim Crow laws, and supporting the KKK,” the California Republican said. “But today, the Democrat Party has simply replaced the racism of the past with the racism of critical race theory.”

McCarthy repeated in a tweet, sent after the chamber’s discussion of the bill, a falsehood that the modern Democratic party holds the same ideologies as its antebellum and pre-Civil Rights era predecessors and, according to John Wagner and Eugene Scott of The Washington Post, failed to “explain how an academic theory is similar to the Ku Klux Klan, which was involved in lynchings and violence against Black Americans.”

Taney, who was chief justice from 1836-1864, wrote the 7-2 majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford, an 1857 decision that interpreted the U.S. Constitution to forbid any person of African descent from ever obtaining American citizenship. According to historian Robert McCloskey, the reaction to the ruling set off a “tempest of malediction” that “stunned” the justices. “[F]ar from extinguishing the slavery controversy, they had fanned its flames and had, moreover, deeply endangered the security of the judicial arm of government,” wrote McCloskey in “The American Supreme Court.” “No such vilification as this had been heard even in the wrathful days following the Alien and Sedition Acts. Taney’s opinion was assailed by the Northern press as a wicked “stump speech” and was shamefully misquoted and distorted. ‘If the people obey this decision,” said one newspaper, “they disobey God.’”

H.R. 3005 singles out the statues and busts of three politicians for removal from public areas of the Capitol, including Charles Brantley Aycock, John Caldwell Calhoun, and James Paul Clarke.

Aycock, an early 20th century North Carolina governor, was an advocate for public education. According to NCPedia, an online glossary of the Tar Heel State’s history, he was also a champion of literacy tests for voting and the poll tax and expanded a state program that “leased” prison inmates, including Black Americans, to private businesses for labor. Eleven Black Americans were lynched during his time in the governor’s office.

Calhoun was Vice President of the U.S. during the administrations of Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. He also served as Secretary of War under President James Monroe and Secretary of State under President John Tyler. But he was also a determined proponent of secession. While serving in the Senate during the 1840s, he sought the annexation of Texas as a means to extend the portion of the nation in which slavery was practiced. In an 1847 speech on the floor of the chamber, Calhoun asserted that “the enactment of any law which should directly, or by its effects, deprive the citizens of any of the States of this Union from emigrating, with their property, in to any of the territories of the United States, will make such discrimination and would therefore be a violation of the Constitution.” This claim, which would have precluded the national government from controlling the spread of slavery if it had been accepted by Congress, presaged Taney’s rationale in the Dred Scott case.

Calhoun also opposed the Compromise of 1850, which was the last significant Congressional effort to avoid sectional conflict over Black Americans’ bondage. His actions in defending slavery are thought by some historians to have emboldened other southern politicians to risk disunion and armed conflict in defense of the practice. Calhoun supported state nullification of federal law and said in an 1837 speech that slavery was a “positive good.”

Clarke, an Arkansas state legislator, attorney general, and governor and later a member of the U.S. Senate between 1903-1916, was a determined white supremacist. “‘The people of the South looked to the Democratic party to preserve the white standards of civilization,” Clarke said during an 1894 political party convention, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture.

During the 116th Congress the House passed a similar measure, which died in the then-GOP-controlled Senate. Colorado Democratic Rep. Joe Neguse was a sponsor of that bill, H.R. 7217.

At present, the Senate is evenly divided between the two parties, with Vice President Kamala Harris holding a tie-breaker vote in the event that the chamber’s version of H.R. 3005 gets past a likely Republican filibuster.