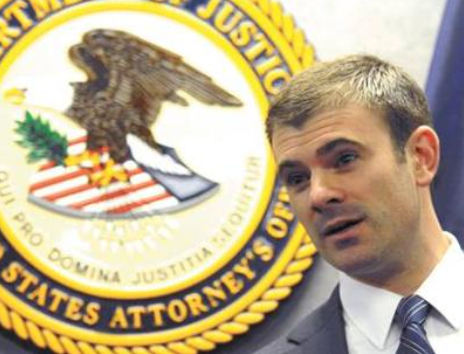

JD Rowell joined the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Colorado on Jan. 6. Rowell moved to the job from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of South Carolina and takes over as criminal division chief.

The following Q&A has been edited for style and length.

LAW WEEK: How does the Criminal Division Chief job work? How much discretion do you have in that role in setting priorities or deciding how to take on cases?

JD ROWELL: If you were to look at our organizational chart, I would say [the position] is squarely in the middle of middle management. I am below the first assistant U.S. Attorney, Matt Kirsch, and then I directly supervise the four criminal section chiefs.

Our four sections are economic crime, national security and cybercrime, narcotics, and violent crime and immigration. And those match our priorities as far as what types of crimes we handle and what problems we have authority to prosecute under federal law.

The Department of Justice has various levels of supervisory approval that is required in every U.S. Attorney’s Office, so as the criminal chief, I have authority to approve charging decisions. I also have authority to approve plea negotiations. As far as discretion to decide what types of crimes we prosecute, they obviously flow from the presidentially appointed U.S. attorney and also from the executive branch. And those priorities are fairly well laid out by the Department of Justice.

My job is to ensure that we’re complying with department policy and then also to carry out the goals and objectives and priorities of the U.S. Attorney, [Jason] Dunn.

LAW WEEK: You already alluded to this being a larger office, and a little bit of a bigger city. What makes the Colorado office different from what your experience has been so far?

ROWELL: The department [of Justice] ranks offices by size. Both South Carolina and Colorado’s U.S. Attorney’s offices are characterized as large districts. South Carolina, I think, was barely a large district. I think Colorado, is solidly on the larger side of large districts. Obviously, Denver being the large city that it is in the center of the country, I would compare it to big offices like the Southern District of New York or the Eastern District of Virginia, in that it’s somewhat of a melting pot. You have people from all over the country coming to live in Colorado, vacationing in Colorado, so that naturally is a conduit for a larger range of criminal activity.

LAW WEEK: What would you say sets your experience apart? What led to you to this point in terms of how you got into this path of being a federal prosecutor?

ROWELL: I think as most lawyers do, you sort of have a view of what the practice of law is when you enter law school that may or may not be grounded in reality — maybe you’re grounded in television or some sort of romanticized view of what lawyers do. After my first semester, I had an opportunity to clerk for a district attorney in South Carolina, and I got to observe a capital case, I got to observe a few violent crime cases and a murder case. And this was all over all over the course of one summer. And really, that was sort of a turning point for me.

I was very interested in law enforcement. I was very interested in the victims’ side of law enforcement and having the ability to interact with people who had suffered as a result of crime, so I made that decision after my first year of law school that that’s what I wanted to do. I ended up clerking for a different district attorney after my second year, and then I was lucky enough to get a job in Greenville, South Carolina, as an ADA. I was a state court prosecutor for four years. In that role, I had an opportunity to really prosecute all sorts of crimes — anything from misdemeanor offenses, DUI, trespassing, and by the time I left that job, I was prosecuting significant drug trafficking cases, assaults, rapes, murders, crimes against persons. And throughout that process, I really enjoyed getting to interact with victims. I really enjoyed getting to interact with juries and judges.

I really saw the practice of federal criminal law as sort of an opportunity to take my practice to a different level. The job of an AUSA is extremely hard to get. It was extremely hard to get in South Carolina, and when I applied and was able to get that position there, I sort of saw that as reaching the pinnacle of criminal prosecution.

LAW WEEK: After Jason Dunn took over the U.S. Attorney position, there was a reorganization within the criminal division, which created the violent crime and immigration section as its own section. How does that type of structure of the different sections affect how you do your job?

ROWELL: In Colorado, we have a cybercrime and national security section, which, based on my time here, reflects the fact that Colorado does have more of those types of crimes than I was used to in South Carolina.

I’m still getting up to speed and sort of learning the rationale behind the restructuring, but my experience has taught me that, to the extent you restructure or you change the way the office is set up, that is really just in response to who we have here and what crimes we are focusing on prosecuting.

I will rely heavily on those chiefs and deputy chiefs to run their sections in the way that they deem appropriate and I will rely heavily on them for input on any strategic decisions we make with respect to staffing those divisions, but they all seem to be to be running extremely well.

LAW WEEK: What have been your career highlights or unique experiences in your prior work?

ROWELL: The bulk of my career in South Carolina is as a line AUSA, I was assigned to our organized crime and drug enforcement task force, so I primarily handled multi-defendant organized drug trafficking prosecutions. I did a lot of Title III wiretap work. Most of the cases that I prosecuted involved several months of electronic surveillance followed by a multidefendant conspiracy indictment.

I did have an opportunity to work on a number of public corruption cases. I had an opportunity to be involved in the prosecution of the chairman of a board of trustees for a historically black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina. At the time, that was that was pretty far outside of my comfort zone. It was primarily a white collar, public corruption case, so having both narcotics prosecution experience and trial experience prosecuting more white-collar, public corruption type cases might distinguish me from other AUSAs in that regard.

Prior to leaving South Carolina, we did have two capital cases while I was there that I supervised at various levels. We had the Dylann Roof, Mother Emanuel Church shooting case that I supervised in part as a deputy chief in the violent crime section and then also as the criminal chief.

And then we have another capital offense that was prosecuted last year, Brandon Council. That was a double-homicide bank robbery case that I initially was the lead prosecutor on and then I supervised.

LAW WEEK: What was your role, and your experience, in the Dylan Roof case?

ROWELL: When the case occurred, I believe I was the deputy chief of our violent crime section. My friend and colleague, Jay Richardson was the lead prosecutor, and you know, given the nature of background, the fact that it was both a violent crime and a civil rights violation, our offices sort of collaborated with respect to how we supervised it. I was consulted on charging decisions early on, and I was a supervisor at the time that the case was brought. I don’t want to suggest that I played a larger role than that of supervisor. But that case occurred while I was in the office, and I had an opportunity to observe that from the front row.

What I learned from that case, and what was very impressive to me, is how the different components of the Department of Justice, like the Civil Rights Division, the Capital Case Section, the Capital Crime Section and the department, come together with a local U.S. Attorney’s office like in South Carolina, to put together the best case possible.

In the department, and certainly this is true here in Colorado, civil rights cases are a huge priority. That case gave me an opportunity to really learn how those national components of the Department of Justice work hand in hand with a local U.S. Attorney’s Office to bring civil rights cases and capital cases.

There were there were AUSAs from our office who worked closely with department attorneys from both of those sections on that case, so that gave me the opportunity to learn that process to see how it brings the department’s significant resources to bear on those cases, that they have national implications.

— Tony Flesor