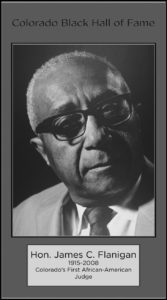

Judge James Flanigan set a “first” for Colorado in 1957 when he became the state’s first Black judge. Nearly a decade before, in 1949, he also became a first for the state when he was appointed deputy district attorney for Denver. Flanigan’s career contributed to many firsts for Colorado and, in 1973, he joined the ranks of Colorado’s Black Hall of Fame maintained by the Denver Public Library.

Flanigan was born in November 1915 and was raised in Kansas. As noted in a 1984 Denver Post article, “he was the first in his family to graduate from college and the first to be a lawyer.” According to a September 2008 Denver Post article, Flanigan told reporters he was originally from Ozark, Arkansas, and was the grandson of a slave. He “hoboed to Colorado on a freight train” from Kansas in 1938 and stayed at the YMCA and later enrolled at the University of Denver, where he gained his undergraduate and law degrees.

According to the Denver Post, Flanigan’s rulings in controversial cases like Denver Urban Renewal Authority v. Pillar of Fire in 1973 resulted in reversals from the state Supreme Court. Flanigan was ordered to reverse his decision that DURA could demolish the church Downtown. The Douglas County News-Press also reported in December 1983 that Flanigan “rejected a request that he block Denver from setting up its traditional Nativity scene on the steps of the City and County building.” The decision drew ire from petitioners who sought the injunction on the grounds that the Nativity scene showed a clear inclination toward Christianity from a city government.

In 1966, he ordered staffers in his courtroom to wear only gray jackets because “it augments the dignity of the courtroom,” according to the 2008 Denver Post article. The article also noted Flanigan bought the jackets himself for $75 each.

Flanigan wasn’t only remembered for his controversial cases, and his online obituary tells a fuller story of his incredible life. One anecdote on his Legacy.com obituary tells a story of how he made an impression on a stranger when she was a child. Flanigan in 1962 stopped to help a family that had been in a car accident on the way to the train station and made sure the family was OK. He gave them a ride to the station himself so they wouldn’t miss their train. “We always appreciated this,” Penny Foley wrote, “and he probably didn’t even think it was a big deal but it was to this six-year-old.”

Dr. Syl Morgan-Smith of Lakewood wrote, “he was a powerful but gentle legal giant known for his legal expertise and compassion.” Morgan-Smith went on to note she publicly crowned him a “Living Legend” and inducted him into the Colorado Gospel Music Academy & Hall of Fame.

The Denver Post noted in its 2008 article that Flanigan was accepted for the state amateur golf championship at Cherry Hills Country Club in 1961, “but when he went to the course he was barred from entry.” According to the Post, “the reason given was that his own golf club, the all-black East Denver Golf Club, wasn’t a member of the state association.” The Denver Post covered the “ensuing uproar” over the decision from the club that later resulted in his admission.

The Post said Flanigan “struck a major blow against racial discrimination in Denver.” He died in August 2008 at 92.