In recent weeks, consumers have seen their inboxes fill up with notifications from companies letting them know they have all updated their privacy policies.

It’s no coincidence. Last Friday the European Union’s new data privacy regulations went into effect, prompting even US companies to retool how they handle consumer and employee data and online consent, or else they will face massive penalties.

The EU adopted the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, in 2016 to bolster the rights that its residents have regarding how their personal data is collected and processed. Among other things, the GDPR gives EU residents the “right to be forgotten,” or demand that an organization erase their personal data. It also lays a host of responsibilities on organizations anywhere in the world that handle EU-based data. These range from conducting impact assessments that gauge their organization’s data security risks to the need to notify authorities of a data breach within 72 hours.

As it turns out, new privacy policies are just a fraction of the monster-sized compliance efforts many US companies — and their legal counsel — have been working on in recent months.

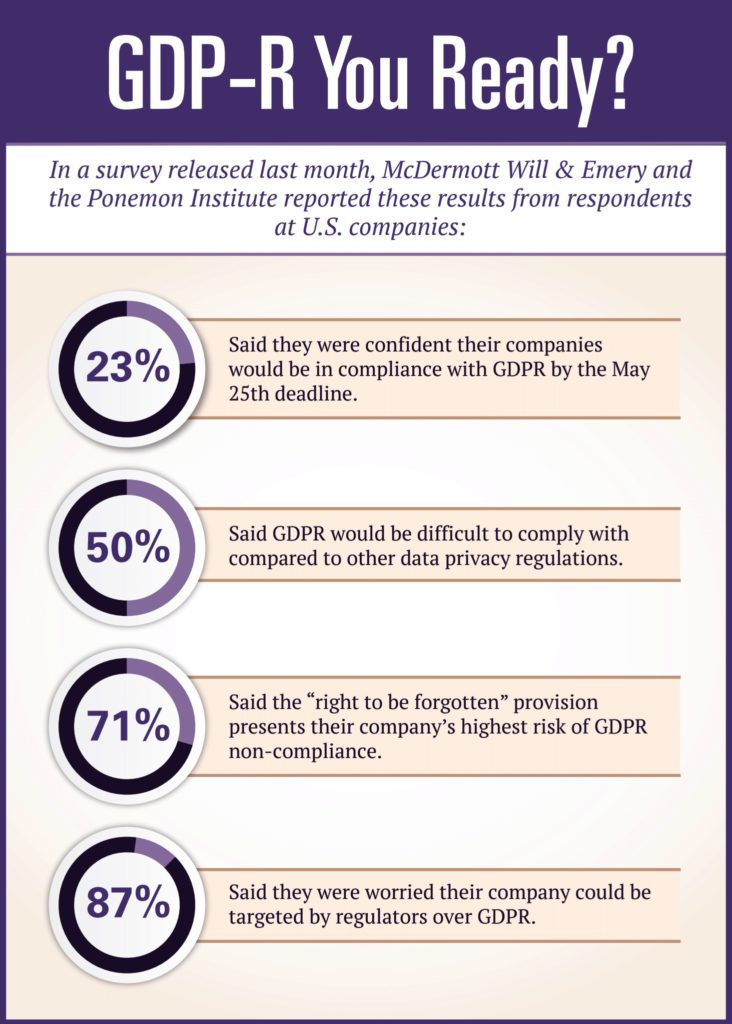

A lot of companies might not be ready, according to research by McDermott Will & Emery and the Ponemon Institute. In a survey published last month, only 23 percent of IT staff, executives and other professionals said they were confident their companies would be GDPR-compliant by the May 25 deadline. Half of the survey takers said GDPR’s data privacy and security requirements, contained across 99 articles, will be more difficult to implement than other such requirements.

Companies have had to start by determining whether GDPR even applies to them, and if it does, when they are a “processor” and when are they are a “controller” under the regulations. A processor is usually the firm that receives EU-based personal data from another entity, the controller, which collects the data from individuals and directs how it needs to be processed. An example of this relationship is a payroll company, which is the processor, that receives and handles staff data as directed by their clients, which are the controllers.

Naturally, GDPR has come up often in conversations between in-house counsel from different companies, who’d ask each other if their company is affected by GDPR, said Gemma Heckendorf, chief counsel at CSG International. “If the answer is no, you tend to say ‘How lucky are you?’ and then move on to the next topic.”

Heckendorf said GDPR prep has made up about 80 percent of work lately at the Greenwood Village-based business tech company. Many of the legal tasks include work on external communications like privacy notices and policies as well as updating customer and vendor agreements. While “it’s not rocket science” in most cases, Heckendorf said, “it’s very time-consuming.”

“It’s a lot,” said Chris Allyn, a business attorney at Moye White whose practice deals in data privacy issues. “I certainly feel for my in-house friends because I was there for a very long time, and operationally [GDPR] is huge.” She was previously general counsel for Quizno’s and has worked in-house for IBM, Ricoh and DigitalGlobe.

The questions Allyn has gotten from clients on GDPR are nearly as wide-ranging as the regulation scheme itself. What are the company’s obligations? How much are they subject to the regulation? Do they have to designate a data protection officer at their company to oversee GDPR compliance? Do they need consent from employees to handle their data? When users give their consent to let the company handle their data, are they really able to withdraw it at any time?

“Companies want a silver bullet,” Allyn said. She added that clients, in seeking ways to fulfill a GDPR obligation, might ask, “ ‘Well, can’t you just give me some language I can put into my contracts?’ The answer unfortunately is no.”

The stakes are high for companies if only because of potential penalties that European authorities could impose for GDPR noncompliance. For the most serious infractions, companies can face a fine as high as 4 percent of their global revenue from the previous year or $23.6 million U.S. — whichever is higher. Eighty-seven percent of U.S. company reps in the Ponemon study said they were worried their companies could face regulatory action over GDPR.

Companies are pouring money into GDPR efforts. A survey by Netsparker of C-suite executives at 300 companies found that a almost quarter of them were spending between $100,000 and $1 million on GDPR compliance, with one in 10 exceeding $1 million in GDPR spending.

Applying the Regs

Part of what makes GDPR tough for U.S. firms to grasp is the chasm between how Americans and Europeans view data privacy. As seen in the demise of the U.S.-EU Safe Harbor Framework for data privacy in October 2015, EU citizens and their institutions tend to push for stricter standards on how personal data is collected and protected.

“In the EU, [data] privacy is a fundamental right,” Allyn said. “It’s a completely different approach than U.S. companies. Their [U.S. companies’] view is they own that data.” Allyn said the overarching cultural aspect of GDPR compliance is something she always touches on when explaining the regulations to U.S. clients.

Camila Tobón, who leads Shook Hardy & Bacon’s international data privacy task force in Denver, said GDPR advice has made up “99 percent” of her practice since January. That’s when a lot of companies “really ramped up” efforts to tackle the regulations, she said.

Contracting seems to be the biggest headache for companies, from what Tobón has seen. Negotiating agreements with vendors and other organizations they exchange data with are taking longer than those companies’ attorneys expected. Tobón said that when it comes to data handling agreements, “the controllers have developed their template, the processors have developed their template” and the dueling templates often collide. Even if the companies contracting with each other have the shared goal of meeting GDPR requirements, they don’t always agree on what those requirements actually mean.

While the processor/controller distinction is a critical one when it comes to drafting agreements, it’s not always obvious which company is which in a given data exchange. Heckendorf said her company previously thought a relationship with an HR vendor made that vendor a processor, but on further review CSG and the vendor determined that they were co-controllers for the purpose of the data transactions.

Some in-house counsel have used GDPR compliance as an opportunity to build more expertise on cybersecurity issues. Linda Ramirez-Eaves, senior counsel of SomaLogic in Boulder, took a week off to earn a CIPP/E certification, which is the International Association of Privacy Professionals’ main certificate in European-based data protection expertise.

When preparing a company for GDPR compliance, the devil is in the details. Ramirez-Eaves said “initially it’s pretty straightforward” for a lawyer to read the GDPR text and the guidance from the Article 29 Working Party, an advisory body on EU cybersecurity standards. “But where it gets tricky is really applying it to your business.”

When SomaLogic, which develops medical diagnostics technology, collaborates with other organizations on clinical trials, it often receives samples that might be considered sensitive personal data under GDPR. That would seemingly require the trial subjects’ consent in order to process the data. “But dig a little deeper, you might find you fall under the GDPR’s exemption for research,” Ramirez-Eaves said.

With some help from outside counsel, she and her company determined that their use of that clinical trial sample data was exempted from GDPR’s strict consent requirements on sensitive personal data, “which saved a lot of work in the end.” That’s an example, she said, of where the learning curve of GDPR implementation becomes more difficult for lawyers — going from the high-level view of the regulations themselves to the “street-level,” applying them to the nuances of the organization’s operations.

‘The End of the Beginning’

With the deadline passed and GDPR live, companies and their counsel are watching to see just how European authorities are going to police the new regulations.

“There are so many questions in my mind about enforcement,” Allyn said. “This isn’t just new for the companies. It’s new for the regulators, too.”

It’s an open question whether the EU supervisory authorities are adequately staffed to the enforce GDPR, and it’s likely they will have to prioritize their regulatory actions. Allyn said “they’re going to try to be reasonable” judging from conversations she’s had with regulators at events and conferences. “What they want to see is that companies are taking [data privacy] seriously.”

Last month Tobón was in London presenting at an IAPP conference, and the gravity of the impending deadline was palpable among attendees. “They talked about the May 25 date almost like [it was] Y2K, but it’s really just the end of the beginning,” she said.

Heckendorf said that for attorneys who are feeling overwhelmed by GDPR compliance, there’s a wealth of resources that they can take advantage of and get up to speed. The IAPP has online references as well as a data privacy listserv that addresses a smorgasbord of GDPR concerns. “Nobody should have to feel like they need to start from scratch,” she said.

Ramirez-Eaves said that in-house counsel are reaching out to each other for advice and best practices on GDPR, doing their best to respond to a broad and often complicated set of requirements. “Part of the experience is figuring it out and making your best effort.”

— Doug Chartier