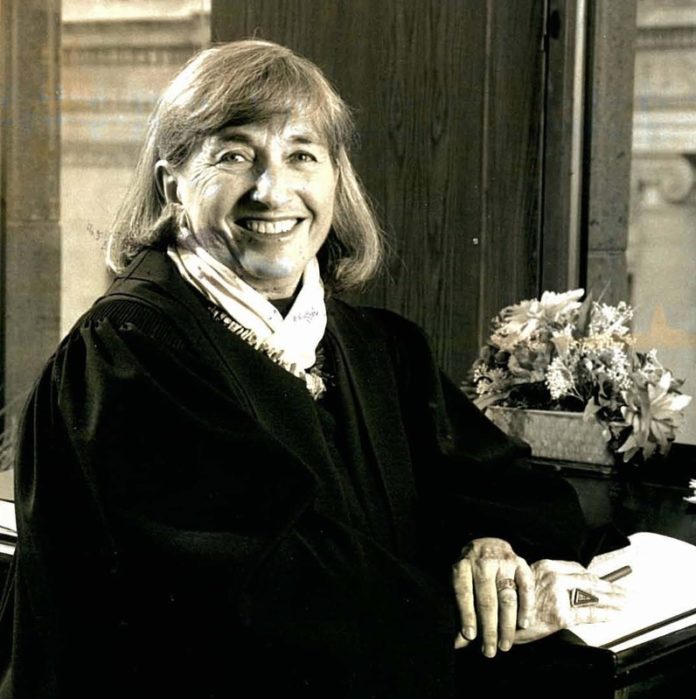

In 1979, Zita Weinshienk became the first woman to sit on the federal bench in the state. She was “one of the first women to do so many things,” according to oral history interviewer Nancy Potter in Weinshienk’s oral history with the American Bar Association’s Women Trailblazers Project. The famous federal judge broke numerous barriers for women in the judiciary.

Weinshienk began pioneering at a very young age – she was among the first women to attend Harvard Law School in the fall of 1955, with the very first class with any women just two years ahead of her. “It was a very brand new situation for the faculty and administration there. And a lot of the professors were so rude, complaining that there wouldn’t be enough ladies restrooms for all of the women,” said Weinshienk in her oral history with the ABA’s Women Trailblazers Project. “That was a concern. Another concern was that they couldn’t tell their dirty jokes because there were women in the class.”

The former federal judge noted in her oral history interview with the ABA that her experience at Harvard Law in those early days of allowing women in the program was at times unpleasant. “I remember one professor who was actually very mean,” Weinshienk said. “We were discussing a case in which someone had been raped and jumped out of a window because she couldn’t stand the humiliation and a lawsuit resulted, and I remember the professor asking me, in front of the class, whether I would have jumped out the window.”

But far from being deterred, Weinshienk became all the more determined. Her classmates and women who proceeded her all felt the same, she said, and noted that Ruth Ginsberg graduated in the class behind her.

After graduating Harvard in 1958, Weinshienk got her start in Colorado the following year when she became a probation counselor, legal advisor and referee at the Denver Juvenile Court. “Well, first of all, I went looking for a job and couldn’t find one and my experience, similar to Sandra Day O’Connor’s, was that nobody really wanted a woman at that time. This was 1959,” Weinshienk recalled of the job hunt in her ABA oral history.

Weinshienk’s job hunt was full of snags, and possible employers asked her to promise not to get pregnant while she was employed with them. She jumped at the chance to build her resume by clerking at the Denver Juvenile Court and took the job over lunch with Judge Philip Gilliam. But back then, Weinshienk noted in her oral history with the ABA, the wage wasn’t great. “It was some outrageously low number. Something like forty dollars a week.”

“When I read ‘The Feminine Mystique’ I suddenly thought, ‘gee, she’s absolutely right and I should have more rights as a woman than I did.’” — Zita Weinshienk

But Gilliam became one of Weinshienk’s great mentors. “There [was] an opening for a county judge and there had never been a woman in Denver county court,” she recalled in the ABA oral history of her first big career move in 1964 to the Denver Municipal Court which later changed its name to the Denver County Court. “Phil Gilliam said ‘Zita, go for it.’” Weinshienk was selected second to the court and during that judgeship commented that the robe was convenient to hide a pregnancy.

“I was concerned that some people would be put-off by having a judge who was pregnant. So it just followed that I should wear my robe,” Weinshienk said in the ABA oral history. “I think I worked as a judge up to three days before I gave birth.” She used vacation time as maternity leave at the time, since maternity leave didn’t exist yet.

“When I read ‘The Feminine Mystique’ I suddenly thought, ‘gee, she’s absolutely right and I should have more rights as a woman than I did,’” said Weinshienk in her oral history for the ABA. “I guess that’s when I became a feminist; it wasn’t really until after law school.”

Judge Gary Jackson was assigned trial deputy for Weinshienk’s court and he recalled “being assigned to her court was a stroke of luck.” Jackson, recipient of the inaugural Judge Wiley Daniel Lifetime Achievement Award by the Center for Legal Inclusiveness in February 2020, said in a Law Week contributed piece that “Weinshienk … possessed a superior intellect and innate wisdom. Her standard of fairness and equal justice for all helped shape my own practice as a lawyer and judge.”

Christina Habas, recipient of the 2018 Kenneth Norman Kripke Lifetime Achievement Award from the Colorado Trial Lawyers Association, said in May 2018 that her childhood ambition to be a judge sparked when her mother, a teacher, took her to the Denver District Court to watch Weinshienk in action. Habas called the experience “a lightning bolt to the head.”

In addition to trailblazing for women in the legal profession, Weinshienk is also credited with being the first judge to preside over a case filmed in its entirety for national broadcast television in 1970.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Portions of Zita Weinshienk’s oral history were granted republishing rights with attribution by the American Bar Association. ©2022 by the American Bar Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission contact the ABA Copyrights & Contracts Department, [email protected], or complete the online form at www.americanbar.org/utility/reprint.html

The brief note about Judge Weinshienk reminded me of law school. I started law school in June 1969. At that time, the law school admitted 150 students to start in June. There were 132 in out class and three were women. A few more women showed up in September, five as I recall of a class of about 150. At that time, there were no female professors and only one restroom in the building for the ladies. When I walked down the hall to go to class, the smell of marijuana was almost always present in front of the restroom. Nowhere else in the building, only there. I wondered just what it was we were doing to our female classmates that required a calming influence. It was dangerous, too. At that time, possesson of any amount of marijuana carried a potential life sentence. I needed something at the law school about three years after I graduated, this would have been about 1975. At that time, the law had changed and there was hardly anyplace in the building you couldn’t smell marijuana.