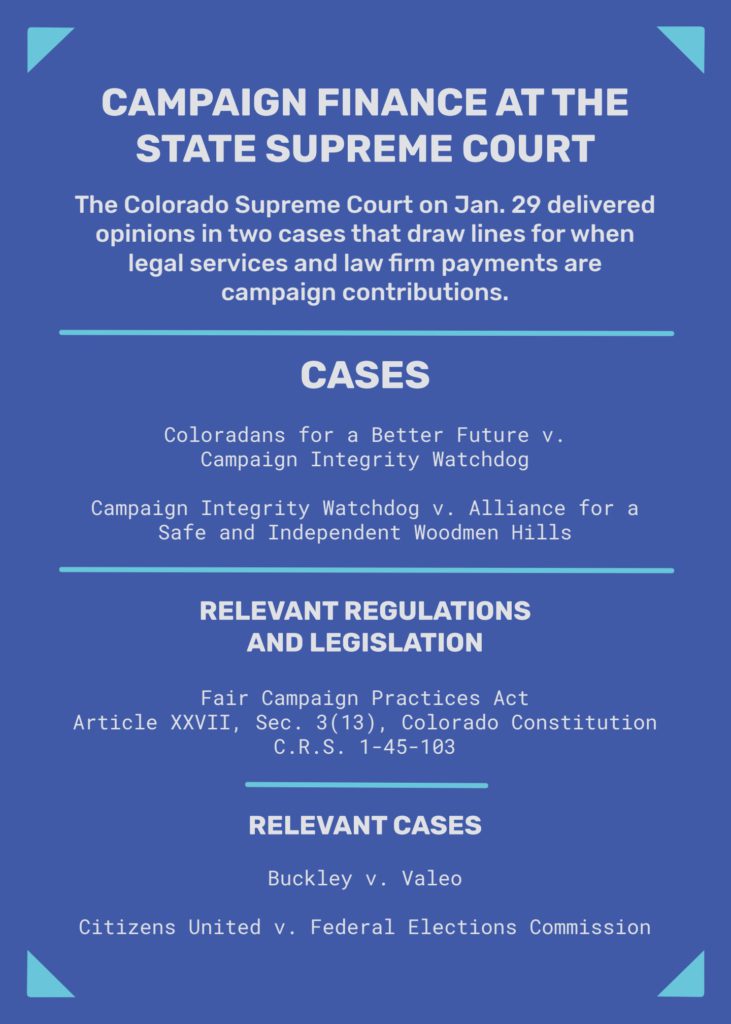

In late January, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in two cases concerning campaign finance. One, Coloradans for a Better Future v. Campaign Integrity Watchdog, centered on the question of whether donated legal services to political organizations are considered reportable contributions. The court ruled that such services are not contributions. Regarding the second case, Campaign Integrity Watchdog v. Alliance for a Safe and Independent Woodmen Hills, the court ruled that payments to a third-party law firm must be reported as contributions as well, but not as expenditures.

Coloradans for a Better Future v. Campaign Integrity Watchdog

In 2012, Campaign Integrity Watchdog founder Matthew Arnold ran for a seat on the board of regents at the University of Colorado. Arnold lost to his opponent, Brian Davidson. The political organization Coloradans for a Better Future ran radio ads supporting Davidson and opposing Arnold. Arnold, acting on behalf of CIW, filed four complaints against CBF concerning campaign finance violations.

An administrative law judge in 2013 fined CBF $4,525 because the organization failed to report the radio ads as election communications. Counsel for CBF Jonathan Anderson represented the organization in this case. Arnold argued that Anderson’s legal services should have been reported as an expenditure or a contribution. In 2014, Anderson filed a contribution and termination report for Better Future. CIW subpoenaed the law firm for records and invoices of the services provided. The firm’s documents showed it invoiced CBF for Anderson’s work in 2013 but not for the termination report filed in 2014.

In response to CIW’s argument that the organization should have reported that work, an administrative law judge ruled that CBF was not required to report these services as a contribution. The Court of Appeals reversed that decision, ruling that CBF was required to report donated legal services as a contribution.

Under Colorado’s campaign finance laws, “contribution” is defined as “perishable or nonpermanent value, goods, supplies, services or participation in a campaign-related event” as well as “any payment, loan, pledge, gift, advance of money or guarantee of a loan made to any political organization.” The statute also includes payments made to a third party on behalf of an organization. In a narrow ruling, the Supreme Court decided that the term “gift” does not include donated services.

“Campaign finance laws are among the most complex laws in America,” Institute for Justice senior attorney Paul Sherman said. “It goes to the core of First Amendment activity and the right to participate in political debate. The Supreme Court decision ensures people can avail themselves of free and reduced cost legal services without opening them up to lawsuits from political opponents.”

Article XXVIII of Colorado’s Constitution enacted campaign finance definitions in 2002. The Fair Campaign Practices Act was amended in 2007, but prior to that, the act did not include specific mention of political organizations. The Supreme Court compared the statute language, concluding that the only the FCPA definition applies to political organizations, but the constitutional definition does not.

Campaign Integrity Watchdog v. Alliance for a Safe and Independent Woodmen Hills

In a 2014 local district board of directors election near Colorado Springs, Alliance raised money to distribute postcards and create a Facebook page disparaging candidate Ron Pace. CIW filed complaints against Alliance because the organization was not registered as a political committee but rather a 501(C)4.

Laws governing political committees, 501(C)3s and 501(C)4 determine what types of actions are allowed by the group. 501(C)4 organizations are primarily considered “social welfare organizations” and are not required to disclose their donors, but political committees are. An administrative law judge fined Alliance $9,650 for violating the Fair Campaign Practices Act because it didn’t register as a committee and did not file expenditure and contribution reports.

Pace filed a defamation suit against Alliance for the election communications.

The district court eventually dismissed the suit and awarded the organization attorney fees. Alliance submitted bills and fees that totaled about $42,000.

CIW filed complaints over Alliance’s failure to report legal expenses in both instances, as contributions or expenditures, and claimed Alliance exceeded the contribution limits for a political committee. In Colorado, the limitation on contributions to political committees from individuals, businesses, expenditure and candidate committees is $575.

Political committees are defined as a person (other than a “natural” person) that has “accepted or made contributions or expenditures in excess of $200 to support or oppose the nomination or election of one or more candidates.”

The Supreme Court sided with the ALJ’s determination that the funds Alliance spent on legal services did not count as an expenditure.

Colorado statute states that in addition to expenditure reporting, committees must also report “obligations entered into by the committee.” CIW argued that this applied to Alliance’s legal services, but the Supreme Court disagreed.

“And it would be absurd to require reporting of all obligations to spend money regardless of purpose yet to require reporting of money actually spent only for a single narrow purpose — express advocacy,” the ruling stated.

The Supreme Court agreed that the legal services should qualify as contributions, but reversed the ALJ ruling that FCPA reporting requirements are unconstitutional in Alliance’s case.

The decision stated that the timing and purpose of a contribution do not matter, because as CIW argued, “elections are cyclical and money is fungible.”

“It’s really the disclosure that’s the crux of the issue. I’ve never been a fan of contribution limits because that really can impact free speech, but disclosure I think is an incredibly important concept,” Arnold said. “Transparency and accountability … is really the key issue. I don’t care how much someone spends, as long as people can know how much are they spending. Where are they getting this money from?”

—Kaley LaQuea