The Supreme Court, in what may be its most significant student freedom of speech decision since the Vietnam War era, ruled in late June that public schools have little authority to regulate teenagers’ off campus social media posts. Fueled by a teenager’s profane post to the social media network Snapchat, the case presented the justices with the question of whether a loophole left in a 1960s opinion allowed administrators to supervise childrens’ online behavior when school is not in session and they are away from campus.

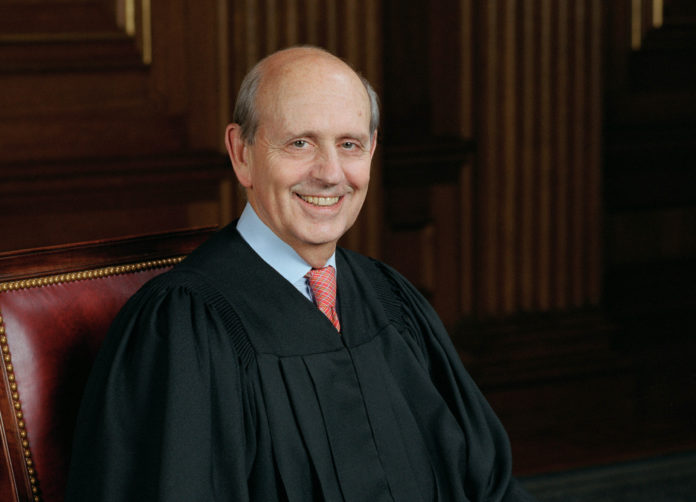

Ruling 8-1 in the case involving a former high school cheerleader, the justices said administrators, teachers and coaches should not assume they have that power. While Justice Stephen Breyer’s cautious opinion declined to “set forth a broad, highly general First Amendment rule stating just what counts as ‘off campus’ speech and whether or how ordinary First Amendment standards must give way off campus to a school’s special need to prevent” disruption of its mission, the court emphasized that school authorities generally don’t stand in for parents outside of school hours.

“Schools can regulate off campus speech, but less than on campus speech,” said Joseph Thai, Presidential Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law. Neither a desire to promote “good manners” nor the goal of avoiding “substantial disruption of a school activity” could justify punishing the adolescent, a now-graduated young adult identified in the case caption as B.L., for her off-campus comments, according to Breyer’s opinion. Instead, and especially when a student’s off-campus comments deal with questions of politics or religion, “the school will have a heavy burden to justify intervention.”

Breyer pointed out that the snaps at issue did not give a tiny Pennsylvania school district a reason to punish B.L. He explained that, because the social media posts were done on a weekend and outside of a school activity, the teenager “spoke under circumstances where the school did not stand in loco parentis.” Breyer used the Latin phrase meaning “in place of a parent.” Breyer also said that none of the teenager’s Snapchats were “obscene,” despite including a common profanity defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as a transitive verb commonly invoked “to express anger, contempt, or disgust,” and did not qualify as “fighting words” — those that “inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace” — or a disruption of school activities.

“I think the message is tread carefully and narrowly,” Thai said. “You have room when the speech is more targeted and more threatening to the school’s educational mission or to the school community, the students and the teachers.”

Thai thinks the court was “admirably careful” and “pragmatic” in avoiding “bright line rules.” “I just don’t think those rules would work,” he said. “You can’t say, in these days of remote learning, that schools cannot regulate off-campus speech. But, at the same time, to give them free reign to regulate off-campus speech just like they regulate on-campus speech, I think would invite overreach on the part of the school administrator.”

The Supreme Court ruled as early as 1923 that public school students have First Amendment rights while on campus. It was not until the late 1960s that the justices first attempted to define just how much freedom of expression K-12 administrators and teachers must tolerate. “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” the court held in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District.” In that case, the court ruled that speech that could “materially and substantially interfer[e] with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” or that interferes with others’ rights can be regulated.

The Tinker holding emphasized a statement by Justice William Brennan in a 1967 decision. “The classroom is peculiarly the marketplace of ideas,” Justice Abe Fortas quoted Brennan as writing. “The Nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth out of a multitude of tongues, rather than through any kind of authoritative selection.” Breyer highlighted that theme in the B.L. case. “America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy,” he wrote. “Our representative democracy only works if we protect the marketplace of ideas. This free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion, which, when transmitted to lawmakers, helps produce laws that reflect the People’s will. That protection must include the protection of unpopular ideas, for popular ideas have less need for protection.”

Thai thinks this passage of the court’s opinion indicates a pan-ideological concern that it is vital to protect students’ freedom to speak on controversial topics. “I would agree that there’s more of the Tinker sort of rhetorical flag-waving about freedom of speech and the First Amendment,” he said. “Breyer has put more teeth into student speech rights than perhaps the [previous] Rehnquist and Roberts court cases, particularly the bong hits case.” Thai referred to a 2007 decision in which the court allowed an Alaska school to punish a high school student for carrying a banner that said “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” during an off-campus activity.

Justice Samuel Alito, in a concurrence joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, explicitly emphasized that goal. Were schools allowed to regulate off-campus speech not connected to learning activities or shared while participating in an extracurricular event, Alito said, then administrators might decide to avoid conflict or controversy by suppressing unpopular ideas. “[It is a bedrock principle that speech may not be suppressed simply because it expresses ideas that are offensive or disagreeable,” Alito wrote. “The overwhelming majority of school administrators, teachers, and coaches are men and women who are deeply dedicated to the best interests of their students, but it is predictable that there will be occasions when some will get carried away, as did the school officials in the case at hand.”

Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter in the case. He argued that, as a historical matter, minors had no freedom of expression rights at the time the Constitution was written and ratified. Thai said Thomas’ dissent continues a pattern of misunderstanding the question presented by student free speech cases. Thai thinks that the question is not whether children have any rights to speak freely, but whether the government can prevent them from doing so. “Thomas, in these free speech cases, has always conflated two different things: the freedom that kids enjoy to speak at home and under the care of their parents or in society versus freedom from government censorship,” Thai said. “He tends to equate their lack of freedom, for example, at the dinner table – you only speak when spoken to – with their free speech up against the government.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, which argued on behalf of the juvenile, called the court’s opinion a “huge victory for the free speech rights of millions of students who attend our nation’s public schools.” “The school in this case asked the court to allow it to punish speech that it considered ‘disruptive,’ regardless of where it occurs,” said David Cole, the ACLU’s legal director. “If the court had accepted that argument, it would have put in peril all manner of young people’s speech, including their expression on politics, school operations, and general teen frustrations.”

Brandi Levy, the former cheerleader at the center of the case, emphasized the need for teachers, coaches and administrators to remember that adolescents are not always aware of the best way to express themselves. “I was frustrated, I was 14 years old, and I expressed my frustration the way teenagers do today,” she said. “Young people need to have the ability to express themselves without worrying about being punished when they get to school.”

Thai agreed that teenagers probably cannot be given school discipline for cursing. “If there’s one takeaway that teenagers can get from this case, it’s that [they] can probably get away with dropping the F-bomb on Snapchat, on the weekends, at home, or [when] going out with their friends, as long as they’re not at a school event,” he said.

The court’s decision in Mahanoy Independent School District v. B.L., No. 20-255, affirmed a ruling by the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.