Most life insurance policies contain a provision under which they won’t pay out death benefits for an insured who commits suicide. These provisions often specifically exclude coverage for suicide committed “while sane or insane.” The Colorado Supreme Court determined that an exclusion with this wording only applies if the decedent intended to kill his or herself. Using this determination, courts might require insurers to prove intent in order to deny life insurance benefits under their “sane or insane” language.

On June 4, the state supreme court answered a certified question from a lawsuit filed in Colorado federal district court. In Renfandt v. New York Life Insurance Company, a woman is suing her late husband’s life insurance company after it denied her claim based on its suicide exclusion. One night Melissa Renfandt’s husband, Mark, was severely intoxicated from a combination of alcohol, prescription medication and marijuana edibles when he shot himself in the head and died.

The plaintiff’s husband had a temporary coverage agreement with New York Life. Renfandt argues that the insurance company should pay the benefits under the policy despite its exclusion for “suicide … while sane or insane” because her husband was too intoxicated to form suicidal intent when he shot himself, therefore his death should be considered accidental.

New York Life had the lawsuit removed to Colorado federal district court, where it filed a motion to dismiss. But the trial court found the “sane or insane” qualifier unclear under Colorado law, and it certified a question to the Colorado Supreme Court. Specifically, did “suicide, sane or insane” exclude coverage for all acts of self destruction regardless of whether the insured intends or understands the consequences of his or her actions? Or did it only exclude coverage for self-destruction when the insured intends to take his or her own life and understands the consequences?

The court leaned toward the latter.

“[I]n Colorado, a policy exclusion for ‘suicide . . . while sane or insane’ still requires an insurer to show that the insured’s death was a ‘suicide,’ ” according to the opinion penned by Justice Monica Márquez. “In other words, an insurer must show that the decedent, while sane or insane, committed an act of self-destruction with the intent to kill himself.”

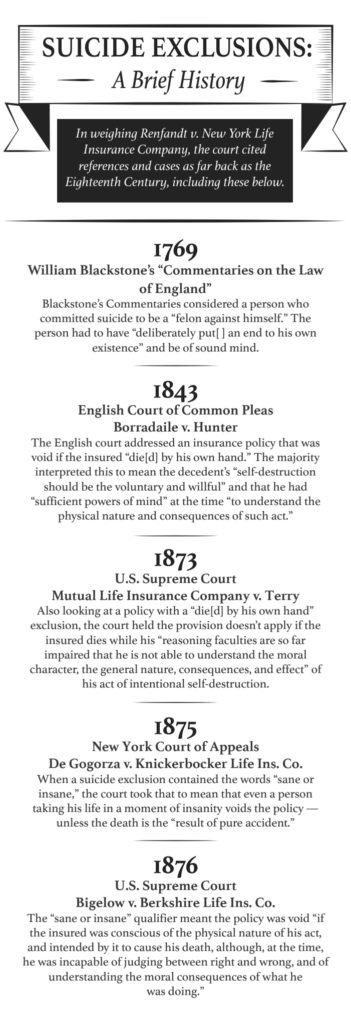

Before the court arrived at that conclusion in the opinion, it analyzed centuries of suicide exclusions in life insurance policies and courts’ interpretations of them in the U.S. and England. The court also had to reconcile Colorado’s own statute addressing suicide exclusions. But it noted that in spite of the long-running debate over whether the insured’s intent is relevant in determining a suicide “sane or insane”, “[i]t does not appear the Colorado appellate courts have addressed this particular issue.”

Colorado prohibits insurers from denying payment on a life insurance policy based on the insured’s suicide if the policy has been in place at least a year. That statute, the court held, “does not bar the provision at issue here (which excludes coverage for ‘suicide . . . while sane or insane’) because the agreement was in effect less than one year when Mark died. Nevertheless, the statute reflects a longstanding public policy in Colorado that disfavors suicide exclusions.”

The court rejected New York Life’s argument that the phrase “while sane or insane” renders intent irrelevant when a person dies by his or her own hand.

“Certainly, a person can be sane and commit an act of self-destruction, yet lack intent to kill himself. … The same is true of a sane person who places a gun to his head as a joke and pulls the trigger and dies, mistakenly believing the weapon to be unloaded,” the court said. “But to the extent that a person’s insanity can, in some cases, render him unable to understand even the physical nature and consequences of his act — and thus negate his intent to kill himself — such lack of intent means only that his act of self-destruction is not, in fact, a ‘suicide.’”

“We’re really pleased with what the court did here,” said Zach Warzel, an attorney at Keating Wagner Polidori Free who is representing Renfandt. The court’s answer “puts the onus back on the insurance company” to prove that the insured intended to end his or her life in order to justify voiding life insurance coverage, he added. The decision “has really broad implications for the insurance industry,” Warzel said.

Lidiana Rios, a Keating Wagner attorney also representing Renfandt, said the suicide exclusion is very common among life insurance policies, and many insurance companies have the “sane or insane” language in them. The decision “lends clarity to what that means,” she added.

A team from Hall & Evans’ Denver office is representing New York Life. The firm did not respond to a request for comment on the supreme court’s decision.

Warzel said it’s not always clear that the insured intended to destroy his or herself, like in a death caused by an opioid overdose. The insurance company can’t just call that a suicide without having to undergo the investigation to determine intent, he added.

As the certified question arose after New York Life’s motion to dismiss, the case in district court is still in a very early stage. With the supreme court’s answer in hand, the insurance company would have to prove suicidal intent to a jury or in a summary judgment motion, theoretically. “I would be surprised given the Supreme Court’s ruling if it were thrown out on summary judgment,” Warzel said.

— Doug Chartier