The Colorado Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Monday about whether it should adopt the final legislative maps chosen by the Colorado Independent Legislative Redistricting Commission.

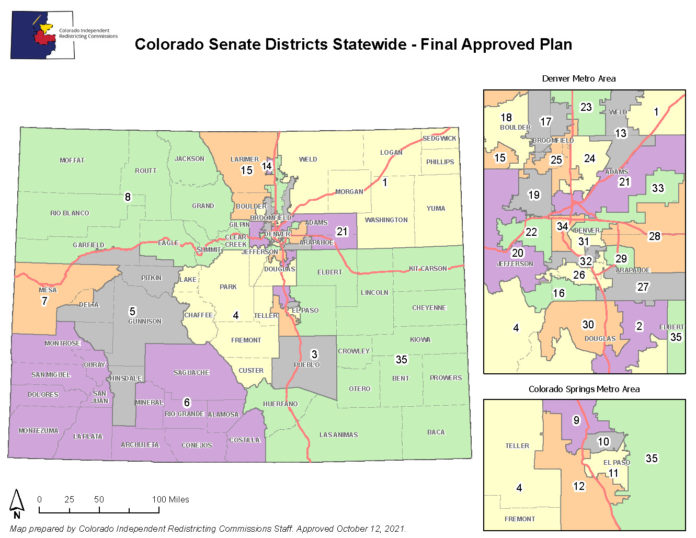

Overall, the legislative redistricting maps were less controversial than the congressional redistricting plan that came before the high court earlier this month, which several groups say dilutes the electoral influence of Latino voters. Many of those same groups were more approving of the final maps for state House of Representatives and Senate districts. Criticism was mostly reserved for the latter, with opponents saying the map should be revised to avoid splitting cities such as Greeley and Lakewood into different Senate districts.

The Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy & Research Organization asked the justices to send the Senate map back to the commission to create a district that contains the entire city of Lakewood. The city is currently split between two Senate districts, but Amendment Z, which was passed in 2018 and created the independent redistricting commission, contains a presumption that cities will fall within a single district except to preserve a community of interest. CLLARO argues the commission didn’t prove by a preponderance of the evidence that Lakewood was split due to “overriding legislative issues.”

Another group, Fair Lines Colorado, raised similar objections about splitting Lakewood. The group said in a brief that “there is no legal justification for splitting a city that in and of itself would compose a State Senate District” and the commission failed to provide a basis for the decision.

Fair Lines also disagreed with the commission’s five-way split of Jefferson County. The proposed Senate District 4 groups about 30,000 Jefferson County residents with residents of Custer, Fremont, Lake, Chaffee, Park, Teller and Douglas Counties. According to the group’s brief, there “seems to be a random assignment with rural counties” and there is no coherent community of interest among them. The group also said the commission didn’t meet its burden in justifying the split.

Former Greeley Mayor Thomas Norton opposed the final Senate plan because it would split his city into two senate districts. Norton argued the commission divided the city to increase the electoral influence of Hispanics, which violates the state constitution’s prohibition against legislative maps that dilute the impact of a racial or language minority group’s electoral influence. By attempting to increase the influence of Hispanics, the commission reduced the electoral influence of all other groups, according to Norton, who previously served in the state Senate and as executive director of the Colorado Department of Transportation.

Pueblo West resident Doris Morgan submitted an amicus brief arguing that the commission abused its discretion by splitting her community into two state House districts. Pueblo West is a census-designated place and represents a community of interest with shared public policy concerns, according to Morgan, and the Colorado Constitution requires the commission to preserve whole communities of interest “as much as is reasonably possible.”

In another amicus brief, Lynn Gerber, a Republican who ran for the state Senate in Jefferson County in 2020, asked the court to reject both the final House and Senate plans. Gerber said the commission’s chosen plans failed to maximize political competitiveness.

The state constitution requires the commission to create districts of equal population, comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, preserve whole communities of interest and political subdivisions, create districts that are as compact as possible and maximize the number of politically competitive districts — in that order. The constitution also prohibits approval of plans that protect an incumbent, candidate or party and bans maps that deny or abridge the right of any citizen to vote due to race or membership in a language minority, including by diluting a group’s electoral influence.

During oral arguments, Richard Kaufman, the commission’s attorney, addressed the objections. Kaufman said Greeley was split because east Greeley has legislative concerns that aren’t shared with west Greeley. For example, he said, east Greeley has a lot of agricultural workers, Spanish speakers and other language minorities that west Greeley lacks.

Kaufman explained that the Lakewood split was meant to preserve communities of interest in Wheat Ridge, Lakewood and along the Sheridan Boulevard corridor. Additionally, Kaufman said, the rationale behind Senate District 4 was that many residents of Park, Lake, Fremont and other rural counties work or shop in parts of Jefferson, El Paso, Teller and Douglas Counties.

Justice Melissa Hart said the record supported the Greeley split but said she “didn’t see quite as much evidence on the Lakewood split.” Similarly, Justice Richard Gabriel and Justice Carlos Samour questioned which evidence in the record supported the Senate District 4 grouping.

As for Morgan’s objections, Kaufman said that Pueblo West is not a political subdivision under the state constitution because it is not a city or town and lines were drawn through the community to meet district population requirements.

Kaufman also addressed Gerber’s concerns about politically competitive districts, noting that competitiveness is at the bottom of the hierarchy for redistricting criteria. The commission had to take other factors into account first, he said, particularly the requirements to preserve communities of interest and comply with the Voting Rights Act.

Kaufman rejected Norton’s assertion that race was the predominant factor in splitting Greeley, contending instead that communities of interest were the top consideration. “The commission believes that there is a substantial equal protection issue under the 14th Amendment” if race is the predominant factor, Kaufman said, echoing concerns raised by the Colorado Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission during oral arguments two weeks ago.

During arguments on the congressional map, Latino organizations and other advocacy groups said the state constitution’s prohibition on diluting minority electoral influence creates a separate and broader protection than the VRA, which says abridging the right to vote due to race or minority language status is unlawful.

The CICRC disagreed, saying the language in the state constitution is meant to codify the VRA’s protections into state law, but it does not create a broader protection when it comes to race. Focusing on race at the expense of traditional redistricting criteria would “put the state on a direct collision course with the Equal Protection Clause,” said CICRC attorney Fred Yarger during Oct. 12 arguments.

Hart asked Kaufman whether he thought the legislative redistricting commission and the congressional redistricting commission shared the same understanding of the state constitution’s language on diluting a minority group’s electoral influence. Kaufman answered in the affirmative, explaining that the legislative redistricting commission believes that language from Section 2 of the VRA was “placed in the state constitution so it would be preserved.”

Republican groups urged the justices to approve the legislative maps. “If the court follows the path that some of the interested parties here would have it follow … then this court or a future version of this court … is going to find itself mired back in redistricting litigation for another generation,” said Chris Murray, representing the Colorado Republican Committee, Colorado Republican State Senate Caucus and Colorado Republican State House Caucus during Monday’s oral arguments.

“This is a chance for this court to set a baseline and to say, ‘this is what a reasonable exercise of discretion looks like,’” Murray said. “If the court chooses not to go that direction, I would put it to the court that the number of interested party briefs is going to multiply and metastasize.”