Justice Neil Gorsuch remained atypically silent last Monday during oral arguments in a case that could significantly alter U.S. labor law and for which he is expected to cast the deciding vote.

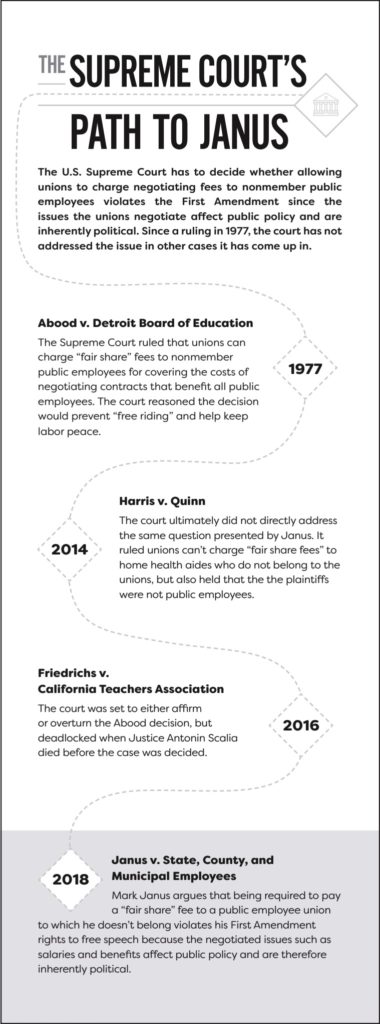

In Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether to overturn a 1977 ruling, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. The decision allowed labor unions that represent public employees to charge “fair share” fees to nonmembers for the costs of negotiating contracts that apply to all public employees.

Mark Janus has argued allowing such compulsory fees violates his First Amendment rights to free speech because the issues public-sector labor unions negotiate, such as wages and benefits, are inherently political since they affect public policy. Although the Supreme Court most recently agreed to review the possibility of overturning the Abood case in 2016 in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, Justice Antonin Scalia died before the court made its decision, and the remaining justices deadlocked.

Sentiment seems to widely expect the court to now overturn Abood v. Detroit Board of Education with the addition of the conservative Gorsuch, marking a departure from other contentious cases in which Justice Anthony Kennedy often casts the swing vote.

William Messenger argued on behalf of Janus, and U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco made arguments on behalf of the U.S. in support of his position. Illinois Solicitor General David Franklin and David Frederick argued in support of the labor union.

Francisco and Messenger argued the wide scope of the effects of collective bargaining in the public-sector context is a core part of what makes it a public policy issue and akin to lobbying. Francisco said the bargaining that takes place between a private union and the government “set[s] the overall size, scope, and structure of government.” By contrast, he argued, an individual employee negotiating over his or her wages takes place only between the employee and employer, even if numerous employees get together to do so outside the umbrella of a union.

Franklin and Frederick argued the union has a compelling interest as the exclusive representative of all employees and in having strong financial support, and “fair share” fees play into that stability of the union. But Chief Justice John Roberts pushed back on Franklin’s arguments that depriving a union of “fair share” fees can cause it to negotiate for short-term gains that attract members back to the union.

“Well, the argument on the other side, of course, is that the need to attract voluntary payments will make the unions more efficient, more effective, more attractive to a broader group of their employees,” Roberts said. “What’s wrong with that?”

Patrick Scully, a Sherman & Howard member who represents employers in labor and employment issues, said although the precise effect isn’t yet clear, the Supreme Court’s eventual ruling in Janus might indirectly affect the private sector as well. In a previous case, the court held private-sector unions could charge fees to nonmembers and section off its political spending from its representation costs, so the fees would only go toward the latter. According to the Colorado Labor Peace Act, representation by a union and forced payment of dues requires two votes by workers, with the second requiring 75 percent of workers to vote in favor.

But a key difference from the private sector evidenced in the Janus case, Scully said, is that in the public-sector context, a labor union requests the government direct money to specific areas of spending, such as benefits and wages.

“The problem in the Abood and the Janus case is that when you talk about a public-sector union, what public-sector unions do is they ask governments to spend money in ‘X’ department instead of ‘Y’ department, even in their representational function,” Scully said. “Which Mr. Janus has characterized as inherently political. … You don’t have that problem in the private sector.”

Scully said he believes that while the labor union has a stronger practical argument because of Abood’s intention to prevent free-riding, Janus has made a better legal case.

“I am sympathetic to the problem that labor has, that they’re providing a service,” he said. “But if you look at it from a legal standpoint, you can see Janus’ argument, because he’s saying, it’s not like the private sector, where you can segregate out the political expenditure. Everything you do in relation to the government in this collective bargaining environment is inherently political.”

Holland & Hart partner Steven Collis, who practices in First Amendment and employment matters, said the Janus case evidences a simmering conflict between unions and companies that runs deeper than just the one case. On one side of the coin, he explained, major corporations have reasons for wanting to reduce union influence. On the other side, those who are pro-labor say the Janus case aims to weaken the influence of labor.

“That’s this bigger battle going on behind the scenes, and it’s a massive political fight,” Collis said. “What the unions are worried about is that over time they’re going to lose all of their influence, especially in the private sector. And as fewer and fewer employees grow up in their careers being parts of unions, then fewer and fewer employees will feel that unions are really necessary, even in the private sector.”

Collis added that because Janus’ case did not make it past the dismissal stage in the trial court or the Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, the Supreme Court may rule in favor of Janus, but choose to remand it back to the trial court for factual discovery.

Scully also expressed the sentiment that the implications of Janus v. AFSCME run deeper than just the one case, saying he believes the true problem the case raises is with labor law in the U.S. He explained that in reality, unions’ obligation to represent employees is not related to how they are funded, because the question of representation is usually only determined by a simple majority vote.

“What’s interesting about the Janus case is that it presents it in the context of governments who, in a lot of cases, don’t have a problem with their employees being unionized,” he said. “But even government employees have this right to be free from financially supporting a union, at least to some extent, and possibly completely.”

— Julia Cardi