An independent redistricting commission submitted its final congressional map to the Colorado Supreme Court earlier this month. But several groups think the commission could do better and are asking the high court to send the map back to the drawing board.

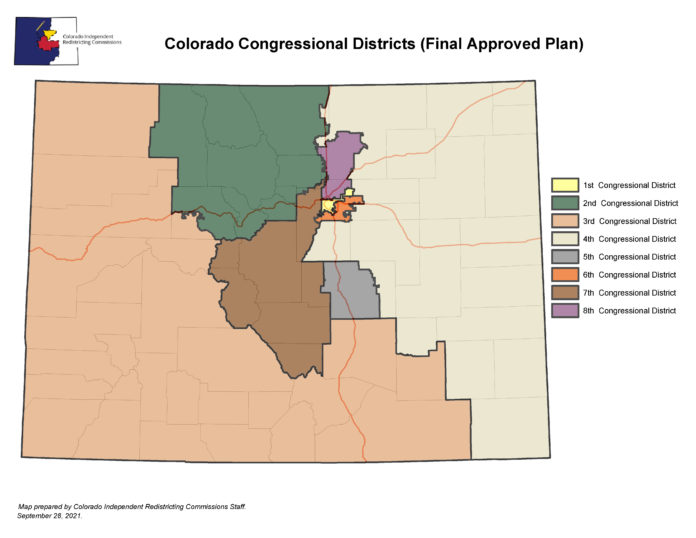

Some want a map with congressional districts that keep Eagle and Jefferson counties whole. Others say the proposed 7th Congressional District, stretching from suburban Broomfield County in the north to rural Custer County in the south, doesn’t make sense. Perhaps most notably, advocacy groups say the commission’s plan waters down the influence of Latino voters across the state.

In its opening brief to the Supreme Court, the Colorado Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission said it “faced a daunting task of adopting one Final Plan from a theoretical universe of thousands.” There was always going to be compromise. “No plan can please everyone,” said Wheeler Trigg O’Donnell partner Fred Yarger, representing the commission in oral arguments before the Supreme Court on Sept. 12.

The commission says its plan complies with the state constitution, which requires the commission to create districts of equal population, comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, preserve whole communities of interest and political subdivisions, create districts that are as compact as possible and maximize the number of politically competitive districts — in that order.

Additionally, Amendment Y, which voters passed in 2018 to create the commission, prohibits approval of plans that protect an incumbent, candidate or party. It also bans maps that deny or abridge the right of any citizen to vote due to race or membership in a language minority, including by diluting a group’s electoral influence.

But Latino groups say the proposed plan does just that. “The plan adopted by the Commission dilutes Latino voters’ electoral influence in southern Colorado and in the northern Denver suburbs,” the League of United Latin American Citizens says in its brief to the high court. The Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization objects to the commission’s final plan for similar reasons.

LULAC and CLLARO say the proposed 3rd and 8th Congressional Districts dilute Latinos’ electoral influence by combining them with white voting blocs that tend to vote against candidates that Latinos prefer.

The final plan’s 3rd Congressional District includes most of the Western Slope, the San Luis and Roaring Fork Valleys and Pueblo County. The new 8th Congressional District would include western Adams County, parts of Weld County and cities such as Berthoud and Johnstown, which straddle Larimer and Weld Counties.

The groups say the commission failed to apply Amendment Y’s prohibition on diluting a racial or minority group’s electoral influence. According to LULAC, the commission interpreted that provision as a restatement of requirements under the Voting Rights Act, which says that abridgement of the right to vote due to race or minority language status is unlawful. But Amendment Y’s prohibition on diluting minority “electoral influence” creates a separate and broader protection than the VRA, the group says, and to read it otherwise would render Amendment Y’s language superfluous.

The commission counters that Amendment Y intended to codify VRA protections into state law, preserving those protections in Colorado regardless of future changes to federal law. In its reply brief, the commission says that the opposing parties “offer divergent approaches” to the minority electoral influence issue, almost all of which “maximally” focus on race at the expense of traditional redistricting criteria. This would “put the state on a direct collision course with the Equal Protection Clause,” Yarger said during arguments.

“I certainly think if the court adopts some of the approaches that the parties are suggesting, this issue will land either in federal court here or will go to the United States Supreme Court,” Yarger said. “And I don’t think the outcome, given the makeup of the court, would be favorable to Amendment Y.”

Another group, Common Cause, argues in an amicus brief that the commission failed to conduct a VRA analysis or explain how its map avoids diluting minority electoral influence.

The concerns about Latino and other minority voters weren’t the only ones raised to the Supreme Court. Fair Lines Colorado, a Democratic non-profit, wants the commission to “fundamentally redesign” the 7th Congressional District. Under the commission’s plan, the district would stretch north into suburban Jefferson and Broomfield Counties, encompass tourism-dependent communities in Teller, Park, Lake and Chaffee counties and dip down as far as “rural, agrarian” Custer County. Fair Lines says the commission had “no discernible basis” for grouping the communities together and failed to state a rationale for why it did so.

Another group, All on the Line Colorado, shared many of LULAC’s concerns about minority electoral influence and Latino voters, but the group’s recommendations for improving the map centered around adding Longmont to the new 8th District.

An amicus brief filed by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee said the redistricting process was “procedurally irregular” and “infused with last-minute confusion.” Census delays led the commission to revise its timeline for drawing the map, setting off a “harried effort” to draw maps, hold meetings and approve a final plan in September. Leading up to the final vote, the DCCC said, “two Commissioners expressed confusion as to what they were actually voting on.”

“Rather than reflect reasoned and deliberate decision making, the Congressional Commission’s 11–1 vote reflects instead a confused process under which Commissioners were unsure of their ability to debate and discuss the merits of competing maps and uncertain as to the very maps upon which they were voting,” the brief states.

Jerry Natividad, a Republican who ran for U.S. Senator in 2016, also took issue with the final plan, which “slices and dices Colorado’s fourth-largest county — Jefferson,” according to his brief. The commission is required by the state constitution to preserve whole political subdivisions, such as counties, as much as is reasonably possible, Natividad says, and the commission could have adopted one of several other maps that kept Jefferson County together.

Eagle County objects to the final plan because it “arbitrarily divides smaller discrete communities” in the county, according to its brief, and it disrupts geographic contiguity of districts.

Not all parties who filed briefs oppose the commission’s map. Douglas County and Summit County submitted briefs in support of the final plan, as did a coalition of Hispanic and multiethnic religious groups with members in the 8th Congressional District.

The Supreme Court has until Nov. 1 to approve the plan or send it back to the commission and the court must approve a final congressional map by Dec. 15.