For most trial attorneys in Colorado, juror questions are part and parcel to trial practice. And in federal and state courts elsewhere, attorneys and judges have been warming up to the once-controversial custom. But the little slips of paper that jurors pass to the bailiff still cause consternation for some courts, and criminal attorneys in particular.

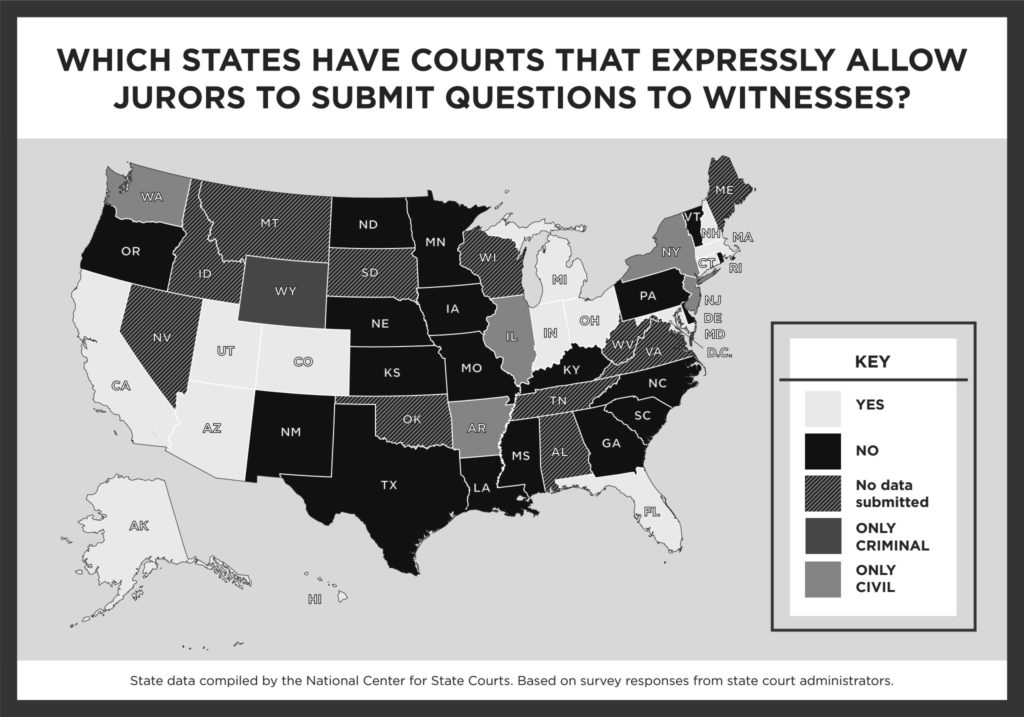

Colorado has expressly allowed jurors to submit questions to witnesses in criminal trials since 2003 and for civil trials prior to that. It remains one of only a few states with a mandate on the practice, along with Arizona and Indiana. Georgia, Minnesota, Mississippi and Nebraska prohibit the practice of juror questions.

The practice has steadily gained traction in federal courts — at least on the civil side. In 2015, juror questions were allowed in 25 percent of federal civil jury trials, according to a nationwide survey by the National Center for State Courts Center for Jury Studies. That was up from 16 percent from a NCSC survey in 2005.

Out of attorneys who had experience with juror questions, about 61 percent recommend the practice and about 16 percent opposed it, according to a 2015 survey by the Civil Jury Project and the American Society of Trial Consultants.

The Civil Jury Project, which is based out of the New York University School of Law, researches the effects and adoption of “trial innovations” that could improve the effectiveness of jury trials. Of the eight innovations it’s studying, which include length limits on trials and juror discussion of evidence before deliberation, juror questions to witnesses is the most widely used and well received in U.S. courts, said Civil Jury Project Research Fellow Richard Jolly.

“Overwhelmingly, [jurors] who do have experience with it think positively of it,” Jolly said.

How It (Typically) Works

In trials where juror questions are permitted, the court often provides each juror a slip of paper as a witness takes the stand, and jurors write their questions on the paper.

Once the witness concludes testimony but before he or she is excused from the trial, the bailiff collects the paper slips. Some courts, in trying to keep the questioners anonymous, collect the slips from each juror whether they wrote questions or not, but others will simply have the jurors raise their hands if they have a question to submit.

The judge reviews the submitted questions with the trial counsel at the bench, where counsel can raise objections to the inquiries. Questions that survive the objections are then read out loud to the witness by trial counsel, the judge or a court clerk, and the witness responds.

Each side’s counsel often has a chance to ask follow-up questions directly related to the juror question.

Pros and Cons

Commonly cited pros to juror questions are that they help keep jurors engaged in the trial and reduce their level of confusion with the evidence presented.

Allowing jurors to ask questions “can also make [them] more involved and observant because they’re in the game,” said Mike O’Donnell, chairman of Wheeler Trigg O’Donnell in Denver. His national civil trial practice has taken him to various federal and state courts across the U.S. where juror questions are implemented.

But the inquiries also give counsel information about the jury they wouldn’t otherwise have.

“When jurors ask questions, sometimes you get a feel for where they are,” said John Campbell, associate professor of the practice at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law. “It provides a window into how the jury is processing the information, which might bring the parties together.” If the questions seem universally hostile to one party, it could persuade that side to try and settle the case, Campbell added.

“I will tell you when a juror asks a question, you’re listening to that question super hard,” O’Donnell said.

He added, however, that while the questions are important to note, their impact on a trial can be overstated.

“The jurors have only spent days or weeks on the case,” O’Donnell said. “The lawyers have spent months and years.” He’s never come across a question from a juror that turned out to be a “game changer” affecting the trial’s outcome, he added.

Juror questions, however, can irk some trial lawyers because they introduce an unknown element to the trial. Campbell said that juror questioning, generally speaking, tends to make “lawyers who like to control everything feel uncomfortable” while more experimental lawyers are more comfortable adapting to it.

Jolly said that among the Civil Jury Project’s survey respondents who don’t like juror questions, some of them say they add little to the trial, but “generally, overwhelmingly, we hear that jurors ask good questions.”

If mishandled by courts, juror questions run the risk of referencing inadmissible evidence or having a prejudicial effect on one of the parties. Other attorneys have complained the process takes up too much time, Jolly added, but there’s no evidence that it dramatically increases the length of trial, according to Civil Jury Project research.

Concerns Persist in Criminal Trials

But the potential drawbacks of juror questions carry more weight in criminal trials. Campbell said it’s common for judges and lawyers in criminal cases to take issue with the juror question process, as it’s more likely involve higher stakes than the civil setting. Some states like Illinois, New York and Washington allow the practice in civil cases but not criminal.

“The criminal context is certainly going to make people more nervous [about allowing juror questions] because you’re no longer talking about money. You’re talking about someone’s life,” Campbell said. Critics have said that juror questions can violate the criminal defendant’s constitutional right to an impartial jury.

Before it adopted a rule to allow juror questions in criminal trials, the Colorado Supreme Court called for a pilot program to study their usefulness and consequences. Mary Dodge’s 2002 report to the court’s Jury System Committee found “that juror questioning has little negative impact on trial proceedings and may, in fact, improve courtroom dynamics.”

In 2005, the Colorado Supreme Court upheld the state constitutionality of juror questions in Medina v. People, a consolidated pair of criminal cases in which defense counsel objected to juror questions but were overruled. The court held that juror questioning doesn’t per se violate a defendant’s right to a fair trial or impartial jury.

That juror questioning is the status quo in Colorado hasn’t sat well with Carrie Lynn Thompson, a former public defender who is the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar’s legislative policy director. She was a vocal critic of allowing juror questions in criminal trials back when Colorado was piloting them in the early 2000s. When she was on the Colorado Standing Jury Committee, Thompson wrote a dissent to the Dodge report.

Thompson disagreed with the report’s “weighing” the benefits of juror questions against the potential harms. If there is only one case where juror questions had a prejudicial impact that led to a defendant’s conviction, or affected a defendant’s choice to testify, “then that is one too many,” she said.

Thompson frequently challenged the admission of juror questions in her own trial practice and trained other public defenders in her office to do the same. “I had lawyers who listened to me, but I had a larger number of lawyers that just are overwhelmed with their heavy caseloads and just didn’t file the pretrial motion,” she said.

She still stands by her minority report, and if anything, she feels her opinion has been reinforced in the years since. Thompson has retired from the Colorado Office of the State Public Defender, and has since been reading trial transcripts, as she’s been retained on issues of ineffective assistance of counsel.

She tends to see lawyers failing to object to juror questions that they ought to. “Not only do they not do it up front,” she said, “once the questions are being asked, they’re missing their mark.”

The unknown variable of juror questions can be especially challenging when it comes to defendant’s decision to testify, Thompson said.

“Every time you have to sit down and make that decision of whether to recommend your client testify or not, and to get them all the information they need to make an intelligent and knowing decision on that, you can’t really predict what questions [jurors] are going to be allowed to ask.”

Try as the attorney might to object, she said, it’s still ultimately the judge’s decision whether certain questions get asked or not.

— Doug Chartier