Judge Stephen Reinhardt solidified his legacy as a “liberal lion” in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals with a significant employment law opinion that came out April 9, just before Equal Pay Day. The court ruled en banc that employers cannot use employees’ prior pay history either alone or in combination with other factors to justify a gendered salary disparity.

Although the decision binds only the 9th Circuit, employment attorneys say Rizo v. Yovino is significant enough to start conversations among employers in other jurisdictions about what is appropriate to ask job applicants.

“If I’m reading this decision as an employer and I’m not in the 9th Circuit, I’m going to think long and hard about [whether I should] be asking about pay history,” said Sybil Kisken, a partner at Davis Graham & Stubbs who practices employment law. “And if so, why am I asking about it? What relevance does it have in my hiring decision?”

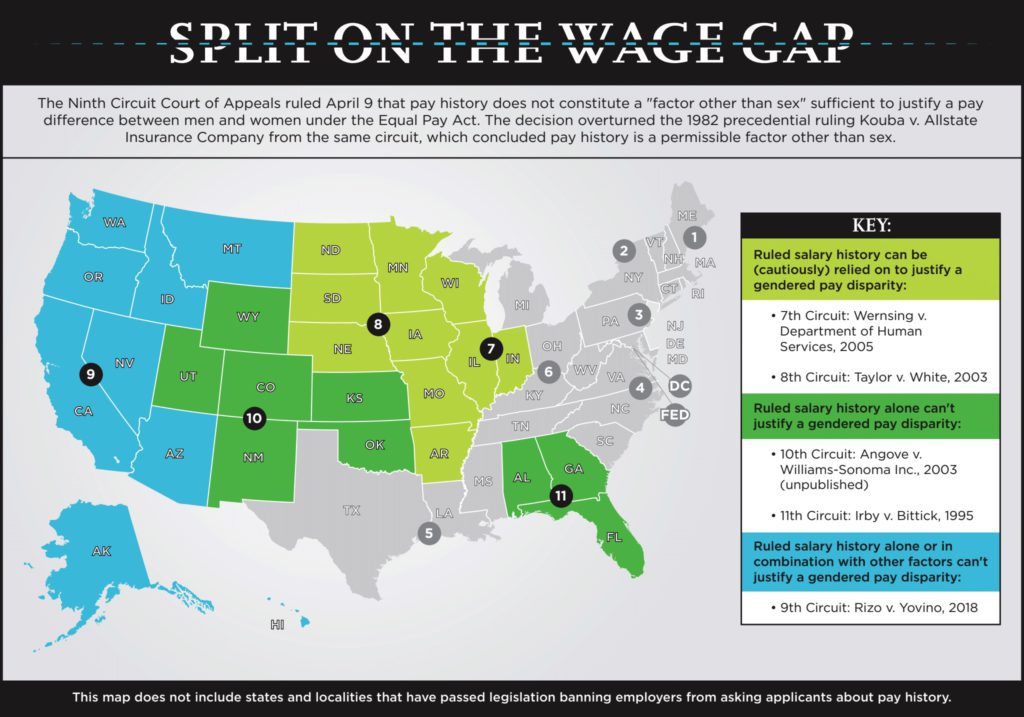

Rizo v. Yovino stands out from prior decisions from the 10th and 11th Circuit Courts of Appeals because it goes further, ruling pay history alone or in conjunction with other factors does not justify a pay gap between men and women employees. The opinion stated that because of the gendered pay gap that has persisted for decades, basing a woman’s pay on her compensation history is discriminatory.

“At the time of the passage of the act, an employee’s prior pay would have reflected a discriminatory marketplace that valued the equal work of one sex over the other,” Reinhardt wrote. “Congress simply could not have intended to allow employers to rely on these discriminatory wages as a justification for continuing to perpetuate wage differentials.”

The 10th Circuit took up the issue in 2003 with an unpublished opinion in Angove v. Williams-Sonoma Inc., ruling employers cannot use pay history as the sole justification for a gendered pay disparity. The opinion joined a 1995 decision from the 11th Circuit in Irby v. Bittick.

But the 7th and 8th Circuits have ruled employers can rely on pay history to justify a gendered disparity. The 7th Circuit ruled on the issue in Wernsing v. Department of Human Services in 2005, and the 8th Circuit decided Taylor v. White in 2005.

The rulings turn on interpretation of the Equal Pay Act’s stipulation that employers can assert “any factor other than sex” as an affirmative defense to a gendered pay disparity. The 7th and 8th circuits ruled pay history does constitute a factor other than sex. They follow a precedential 1982 9th Circuit ruling in Kouba v. Allstate Insurance Company, which Rizo v. Yovino overturned.

Kisken said she could see the U.S. Supreme Court taking up the issue eventually because of the split among circuit courts.

The Rizo v. Yovino opinion later clarifies it doesn’t intend to eliminate salary history altogether from individual salary negotiations, just that it can’t be used to justify gendered pay disparities.

“Today we express a general rule and do not attempt to resolve its applications under all circumstances,” Reinhardt wrote in the opinion. “We do not decide, for example, whether or under what circumstances, past salary may play a role in the course of an individualized salary negotiation.”

McNamara & Shechter partner Mathew Shechter, who represents employees and unions, said he believes the opinion seems to have set a bright-line rule about pay disparity. He added he expects the defendants in Rizo v. Yovino to petition the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I think the language is very strong … that should give employees some hope that litigating these issues, especially in the 9th Circuit, will be successful,” he said. He said he believes the 10th Circuit likely would have made the same ruling because precedent in the jurisdiction has held pay history alone can’t justify a gendered pay disparity.

Kisken said she interprets Rizo v. Yovino to mean if pay history is considered, it must also be looked at in conjunction with factors such as experience or education. The question that naturally follows, she said, is how to apply the 9th Circuit’s rule.

Kisken compared the issue to limitations under the Americans with Disabilities Act, which has clear restrictions about what employers can ask applicants before extending a job offer but also contains guidance about what do if a person’s disability is obvious or if they volunteer information about it. She said she sees the salary history issue similarly.

“If I as an employer am asking you about your salary history, the question that the employer needs to be able to answer is, what is that relevant to in the discussion? And I think the 9th Circuit’s point is it’s not directly relevant to anything that’s job related,” she said. “At the same time, [Judge Reinhardt] seems to be saying … if somebody volunteers salary history as a basis for negotiation, then that does seem like a legitimate issue for a potential employee to put on the table.”

Kisken and Shechter said Rizo v. Yovino is a distinctive case because plaintiff Aileen Rizo’s pay as a school district math consultant was part of a “step” system, in which her compensation was directly based on Rizo’s pay in her previous position. Even under the prior rule in the 9th Circuit, that was unlawful, Shechter said.

“I do think it will have some influence” even if the Supreme Court does not hear Rizo v. Yovino, he said. “Traditionally in employment cases, the 9th Circuit often is on the leading edge, and so employee advocates will use that to try and change the law in other circuits.” The important remaining question, Shechter said, is how the 9th Circuit and other jurisdictions will approach future cases in which the facts are not as black and white.

Legal Versus Practical Viability

The legal and practical considerations for the Equal Pay Act diverge. The statute is intended to give employees an advantage in gender-based pay disputes, Shechter said, because unlike Title VII, it is a strict liability statute where the employee does not have to prove the employer’s intent to discriminate. That shifts the burden to the employer to prove a sufficient defense for a gendered pay disparity.

But from a practical standpoint, the Equal Pay Act has limited usefulness outside the public sector because of the lack of transparency about pay, Shechter said. Private employers do not have to publicize compensation information.

“Without salary transparency, Equal Pay Act claims in private circumstances are very difficult to ultimately prove, simply because you’re not going to be able to gather that evidence without first filing a lawsuit,” he said. “The Equal Pay Act is a strong [statute] legally, but for practical reasons, unfortunately it’s not particularly helpful to most employees.”

Precedent for publicizing information related to protected classes exists in the context of age discrimination. Under the Older Workers Benefit Protection Act, Congress required employers in workforce reduction situations to notify employees about the ages of those laid off and not laid off.

“If we’re doing that sort of thing for age discrimination, why shouldn’t we be doing it to correct equal pay violations?” Shechter said. But he said he believes legislation requiring disclosures of pay information is likely a long way off.

Several states and localities have passed policies placing various limitations on employers’ use of pay history in the employee search and hiring process. Some include Massachusetts, California and New York, but a bill in Colorado barring employers from asking applicants about their pay history died in a Senate committee in 2016.

Shechter said he hopes the #MeToo movement will have a trickle-down effect on gender-related workplace issues in addition to sexual harassment.

“I think pay equity is the next big step on the radar, and so I hope that we get there.”

— Julia Cardi