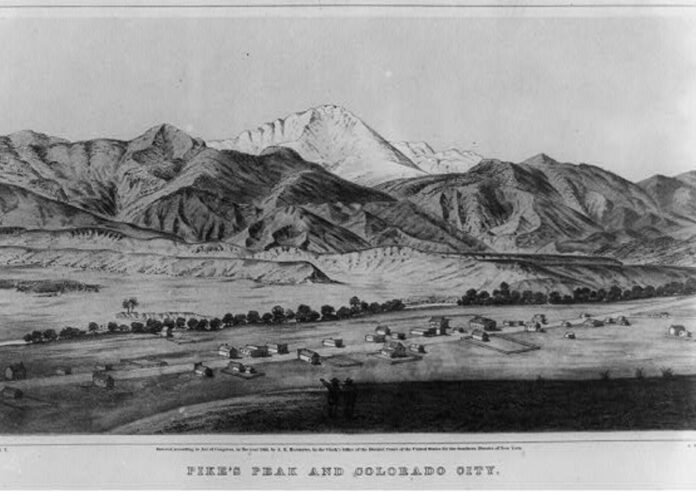

There are many factors that drive people to move to Colorado, but in the late 1850s, there was a largely singular draw: the Pike’s Peak gold rush. With the sudden arrival of thousands seeking their fortune, both newcomers and existing residents faced the challenge of maintaining law and order in the fast-growing and often transient settlements around mining claims.

To solve this, the new settlers formed mining districts, one of the earliest forms of local government in Colorado.

Writing in the Denver Law Review in 1959, James Grafton Rogers, former president of the Colorado State Historical Society, commented that law began in Colorado in 1859. “It took the form of legislation, courts and trials set up and administered by many little local governments created by the gold miners themselves,” Rogers wrote.

These local governments, according to Rogers, lacked the imprimatur of any formal authority. Instead, the districts drew their legitimacy from mass meetings held in the mountains by groups of prospectors residing in the territory.

These districts operated as commonwealths. Rogers noted that many had elected officers, executives, judges and police, along with treasuries, written files and property records. Some even developed judicial procedures and substantive criminal and civil law.

In Gilpin County, for example, court membership was open to all interested parties, according to the Colorado Historical Society. The rules of conduct, offenses and punishments were determined by the participants of the court. In cases of theft, a convicted offender had to pay back double the property value. For grand larceny, the offender faced the same restitution requirement but was also banished from the mining district.

Juries also played a role in Gilpin County. Trials of those accused of manslaughter or murder included juries, and their sentences were subject to the approval of the court members.

The provenance of mining districts often extended to miners’ claims, even detailing how much water miners were allowed to use.

The laws of the districts weren’t static. As new issues arose and conditions changed, the laws were revised, amended and recodified, according to an article by Thomas Maitland Marshall in the American Historical Review. “The later enactments were more complex and more technical than the earlier laws, and new offices with clearly defined functions were created,” Marshall wrote.

One issue that caused particular outrage in the mining camps, according to an article in Colorado Magazine, was street maintenance and similar collective concerns.

The article cited a Deadwood newspaper editor from the time who wrote, “We are slow to invest our hard earned money, unless we are compelled to, in any public good, simply because of the disposition on [the] part of many to head off any enterprise unless they can see an individual benefit arising from it, and there are those who will throw every obstacle in the way to defeat great undertakings.”

While the mining districts were short-lived—fading with the organization of the Colorado Territory in 1867, followed by statehood in 1876—their legacy endured.

According to the Colorado Historical Society, the courts established by the federal government in the territory often recognized the laws and precedents established by the miners’ courts and their people’s courts counterparts in communities and towns across the territory.