U.S. law firms are currently experiencing a slowdown in some respects. But one thing that’s picking up speed in the legal market is the number of law firms joining up across the country.

The Altman-Weil MergerLine reported that 2017 was a “record-breaking year” in U.S. law firm mergers and acquisitions. Last year’s 102 law firm combinations topped the previous high of 91 reported in 2015.

In the Philadelphia-based firm’s announcement, Altman-Weil owner Tom Clay called the nationwide law firm merger market “white hot.” But what’s Colorado’s climate when it comes to law firm buyers and sellers?

Over the past decade, 22 Colorado-based firms merged or were acquired, according to Altman-Weil. That placed Colorado ninth among states during that period — below Ohio and above Washington, D.C. The biggest Denver-based firm acquired in the past 10 years was Holme Roberts & Owen, which had 159 attorneys when it combined with Bryan Cave in 2011.

Next to Los Angeles, Denver was the No. 2 most-popular destination in the West for a law firm acquisition or merger from 2007–2016.

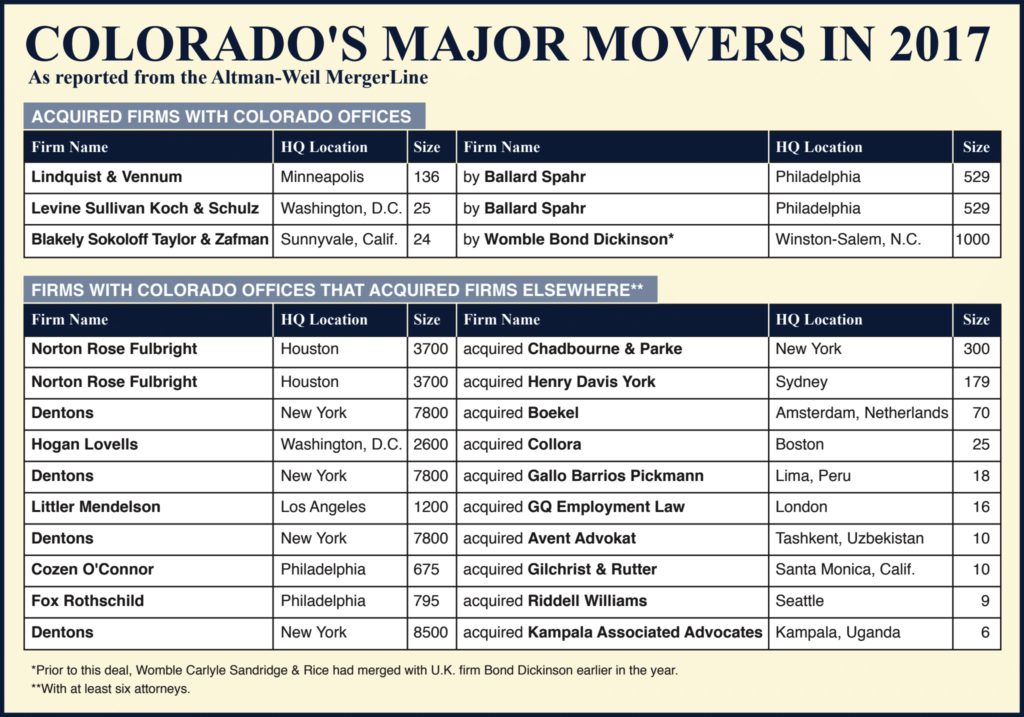

Last year, Colorado saw three major combinations with firms that had Colorado offices. Philadelphia-based Ballard Spahr acquired Lindquist & Vennum, a firm headquartered in Minneapolis that had 23 Denver attorneys when the deal was announced in September. The next month, Ballard Spahr took on media and First Amendment-focused boutique Levine Sullivan Koch & Schulz. In December, Blakely Sokoloff Taylor Zafman, a California-based IP boutique that had a presence in Denver, was acquired by Womble Bond Dickinson.

The Denver legal market’s M&A climate is “very active and likely to grow significantly,” said Roxanne Jensen, a law firm consultant who does business planning through her Denver-based firm, EvolveLaw.

Jensen worked on the 2013 merger between what was then Lewis Roca and Rothgerber Johnson & Lyons. In her experience, she’s seen M&A inquiries to Colorado firms only become more frequent since then — almost too frequent.

“It’s hard for managing partners to even think seriously about them because there are so many flooding in,” Jensen said. While Colorado continues to be an attractive destination for expanding U.S. firms, over the last year Colorado hasn’t matched the hotbed of acquisition activity in Texas or Minnesota. Jensen said the difference is that while M&A talks abound in Colorado, they aren’t seen through to execution at the same rate as in some other U.S. legal markets.

Firms taking ‘smaller bites’

Small firms continue to make up an overwhelming majority of acquisitions nationwide. From 2007 to 2016, 78 percent of law firm combinations were acquisitions of firms from two to 20 lawyers.

Last year, that number was on trend with 80 percent.

The legal market is rapidly changing yet experiencing hardly any growth post-recession. A study released earlier this month by Georgetown Law and Thomson Reuters Legal Executive Institute showed flattening demand for law firm services and shrinking profit margins.

That might only increase the pressure for law firms to grow strategically in smaller increments rather than swing for the fences on a mid-to-large-firm combination.

“Increasingly, law firms can’t afford for mergers to fail,” Jensen said. That might be a driver for why the market has preferred smaller mergers, where firms take “smaller, good bites,” rather than larger acquisitions that carry more risk if they don’t work out, she added.

Half of merger failures are due to poor vetting of the other firm and poor alignment between the two businesses and cultures, she explained, and the other half are due to poor integration post-deal. “Those two things are hard,” Jensen said.

Suitors from elsewhere

So there’s reason to expect that firms of 20 or fewer lawyers, including those in Colorado, will continue to be the most attractive acquisition targets. But in the Denver area’s relatively healthy legal market, firms may be less inclined to join with another if they feel they’re getting along fine on their own and see a clear path forward in terms of succession and business plan.

“The Denver marketplace is doing better than many, so in some ways that makes Denver boutiques and practice groups harder to court,” Jensen said.

Still, many out-of-state law firms might consider acquiring a local firm as their point of entry into the Denver market. And while coastal players might still have interest in doing that, it’s generally trickier for them to combine with a non-California firm in the West because they’re less financially compatible, Jensen said.

Clients in Colorado might not be inclined to pay New York or San Francisco rates after the merger. And because a Denver partner will likely not bill as much as a coastal partner in the same practice group, a cross-country merger can create “different classes of partner,” she said. That’s partly why there have been so many firms from the Midwest moving into the Denver area, as there’s more likely to be a “financial and cultural alignment,” Jensen added.

— Doug Chartier