Two sets of measures concerning state legislative and congressional redistricting in Colorado are currently before the Secretary of State and the state Supreme Court, each vying for victory in the form of inclusion on the 2018 state ballot. And though both initiatives aim to change the state’s redistricting process, the proponents of the measures have fundamental differences on the best way to approach reform.

The nation’s 435 districts are divided and determined by population, with an average size of 711,000 for each. The 2010 census reported that Colorado’s population was 5,029,196. Population estimates as of December 20 for Colorado were at 5,607,154. After the 2000 census, Colorado gained a seventh representative. And an analysis of census data from Election Data Services anticipates that an eighth will likely be gained after the 2020 census as well, though that also depends on growth and loss in other districts.

Redistricting refers to the drawing of boundaries to reflect population changes after the decennial census. In 1974, Colorado voters adopted a constitutional amendment that created a reapportionment commission, which is tasked with drawing the state’s 65 House of Representatives districts and 35 state senate districts.

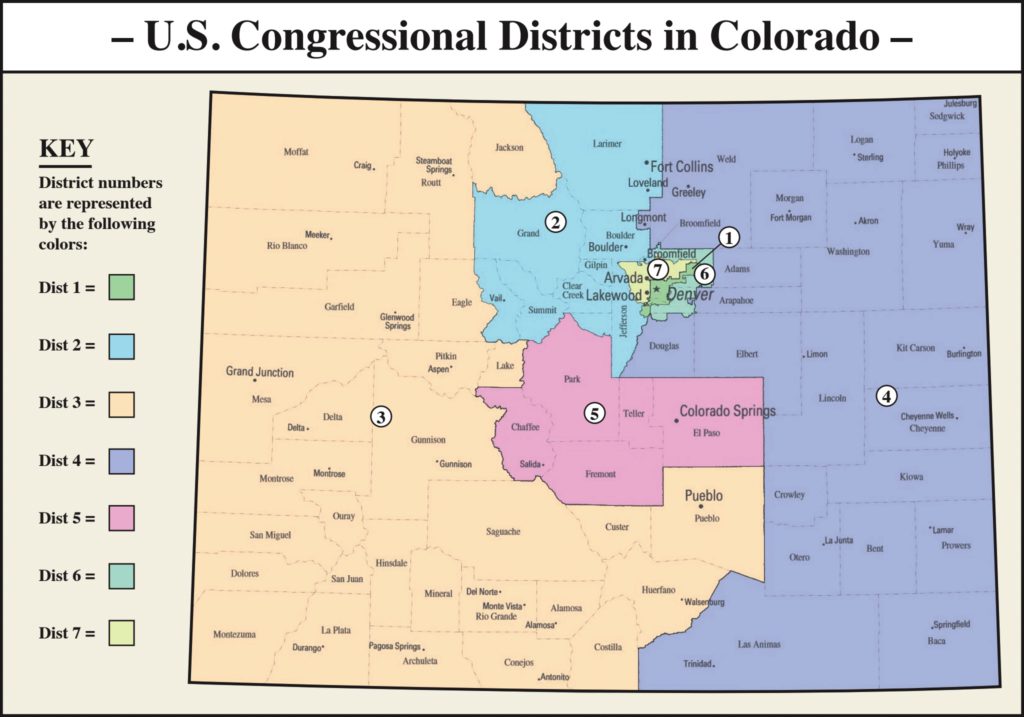

The 11-member commission is appointed by the legislative leaders in the House and Senate, as well as the governor and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Colorado has seven congressional districts. Currently, the state legislature draws those boundaries. With Colorado’s population projected to swell to more than 5.9 million by 2020, the two competing groups trying to implement new redistricting procedures have their work cut out for them.

Initiatives 67, 68, 69

The effort, driven by Fair Districts Colorado and the League of Women Voters, advocates for alterations to state legislative district maps to be carried out by an independent commission. The 12-member commission would be composed of four individuals from the state’s largest political party, four from the second-largest party and four unaffiliated members. Incumbents or candidates from the legislature are not eligible for the commission.

Appointments will be made by House and Senate majority and minority leaders for the two parties. Independent commissioners will be recommended by a panel of senior judges (Initiative 68 calls for retired judges), assembled by the Secretary of State. The secretary will then choose independent members from those recommendations for each congressional district that isn’t represented by the eight party commissioners. No more than three members can live in the same district.

In a redistricting year, the governor would appoint a chairperson, and the commission would select a president and vice president from different parties. The commission would be open to receive and review comments from voters on redistricting plans for both houses. Once a preliminary plan is created, the commission will hold public hearings and receive feedback. The final plan will be submitted and approved by the Colorado Supreme Court.

Initiative 69 proposes an independent commission with the same makeup to revise and submit congressional districts to the Supreme Court.

Proponents for the measures include two former Colorado governors and a bipartisan group of former legislators. The campaign emphasizes the importance of independent and unaffiliated voter inclusion in Colorado. Former independent state representative Kathleen Curry was the first independent legislator to serve in the state, and feels that an independent commission approach is essential for representing all of Colorado.

“I knew we needed change and this group was committed to independent unaffiliated voters in Colorado, and making sure independents had a seat at the table and were directly involved in the process,” Curry said. The three measures are currently pending a decision by the Supreme Court.

Last year, a handful of measures failed to reach the ballot on the issue. Four were brought by Curry and former Republican House Speaker Frank McNulty. Attorney coalition Strengthening Democracy Colorado aided in the drafting process, but the Supreme Court stated the measures violated the single subject rule. The decision came too late in the process to restart for 2016. Opponents of this year’s measures filed an appeal on the same violation with the Supreme Court.

“Gerrymandering is a major concern nationally,” said Ireland Stapleton of counsel, Bill Hobbs, who is representing proponents of measures 67, 68 and 69. “It creates safe seats where a general election is not competitive and undermines the ability of voters to have a meaningful say in an election.”

In order to get a measure on the state ballot, proponents have to collect the number of signatures equal to 5 percent of the total number of votes cast for the Secretary of State at the previous general election. For 2018, that number is 98,492.

Initiatives 67 and 68 are constitutional, meaning if the Supreme Court approves the measures, proponents will have to meet state geographic requirements. Amendment 71, passed last year, requires at least 2 percent of registered voters’ signatures in each of the state’s 35 senate districts. The measure must also receive 55 percent of all votes cast to pass. A simply majority is required only if the measure aims to appeal part of the constitution.

Initiatives 95, 96

Community advocate Robert DuRay and Mi Familia Vota Colorado State Director Carla Castedo are leading the way for the two measures. Initiative 95 and 96 also propose 12-member independent commissions through a different process. Staff from the Office of Legislative Council and Office of Legislative Legal Services will review applications from individuals who:

• illustrate they have experience in representation and advocacy for interest groups, including organizing, public support for policy objectives;

• meet affiliation requirements for one of the state’s two largest parties, or are unaffiliated with any party; and

• have voted in the last two general elections.

Six individuals will be chosen by the staff: two unaffiliated (and haven’t been affiliated with any party in the past three years) two from the state’s largest political party and two from the state’s second largest party.

The staff will then give a list of names from the remaining pool of applicants (from the two parties) to four legislative leaders. Those leaders must select 10 names from each, and the staff will select at least 10 names (no more than 20) from the unaffiliated voters pool. The names from all groups will be given to the Chief Judge of the Colorado Court of Appeals, who will choose one commissioner from each of the leader’s pools and two from the pool of unaffiliated voters.

Recht Kornfeld shareholder for proponents Mark Grueskin says measures 67-69 are the same old system in which legislative leaders appoint members, and fail to accurately represent Colorado.

“It’s not enough to say the 12 commissioners are roughly reflective of the geography of Colorado,” Grueskin said.

According to Fair Districts Colorado’s website, state and federal statutes include several criteria for drawing district boundaries:

• Equal population: Each district in a state must have roughly the same number of people

• Contiguity: All areas within a district should be “physically adjacent”

• Density: The distance between all parts of a given district should be minimal

• Communities of interest are preserved

And finally, the organization’s website states that “competitiveness prohibits districts from being drawn for the purpose of favoring or discriminating against a political party or candidate.”

A Different Approach

Strengthening Democracy Colorado withheld support for this year’s measures, citing concerns about the creation of competitive districts over independent ones. Fair Districts Colorado aims to represent unaffiliated voters and non-major parties.

But SDC executive director Jason Legg said that the “guaranteed” representation for Colorado’s 1.1 unaffiliated voters could end up going to the state’s minor political parties that “no more represent these voters than the major parties do.”

“If you’re starting from scratch, I don’t understand why it’s been so difficult to clean up,” Legg said. “It makes me worried about people’s motivations.”

Grueskin said other approaches offer false promises of truly representative commissions and districts.

“When it comes to the goal of competitive redistricting, they’re fool’s gold in terms of being able to deliver on that promise,” he said. “There also stands the very real possibility that under 67-69, there will be no racial and gender diversity on the commissions, and decisions will be made that don’t represent Colorado.”

Legg said measures 67-69 conflate the idea of creating competitive districts with districts free of a partisan hold. Castedo, who became a naturalized citizen in 2014, registered to vote for the first time with Mi Familia Vota and says that ensuring a transparent and accessible process is a personal and important endeavor.

“Our proposition ensures that people are the ones making the decision,” she said. “Maps would be drawn in a public and open process, not behind closed doors, and anyone can submit a map. At the end of the day, we elect politicians to serve us, not the other way around. Implying that other initiatives are only trying to protect minority communities of interest by relying on politicians to do what they think is best is insulting and patronizing.”

The draft of Proposal 95 says that the decision to choose two commissioners from a pool of unaffiliated voters is specifically to “enhance[e] the commission’s racial and gender diversity and assur[e] representation of all the state’s existing districts.”

Arizona became one of the first states in 2000 to enact an independent commission for drawing boundaries, and California followed in 2010. But the states had vastly different approaches. While Arizona’s commission was instructed to explicitly consider partisan data, California’s was banned from doing so. And though Arizona’s maps after redistricting in 2001 and 2011 were among the most competitive in the U.S. (those that had a victory margin of less than 10 percent), California’s 2011 margin of victory, based on the nonpartisan commission’s maps, was 30 percent lower than the legislature.

Grueskin said that even in the event that both sets of measures make it onto the 2018 ballot, the differences between them are ‘glaring,’ and he trusts the voters of Colorado.

I think the [other] proponents have seen the value of some of our ideas, and there’s already been a foray on their part to say ‘Maybe we ought to sit down and talk,’ so we’ll see whether two sets are presented [on the ballot],” he said. “Voters in Colorado are smart and informed and caring about how they revamp their government, I don’t think they’ll be easily convinced that just any commission that’s been proposed is the right idea.”

— Kaley LaQuea