In the wake of the sexual abuse scandal uncovered earlier this year in USA Gymnastics, former doctor Larry Nassar, USA Gymnastics board members and Michigan State University officials were held accountable for Nassar’s rampant abuse and subsequent coverup. But a lawsuit filed in federal district court in Colorado targets the U.S. Olympics Committee to dismantle what plaintiffs’ attorneys describe as a culture where “athletes are disposable, and the quest for medals and money trumps all.”

“We’ve got to stop looking at this in silos — this is all the USOC. It’s all the same people in all the same sports, passing these guys around and covering for each other and allowing these guys to get away with it,” Saeed and Little partner Jonathan Little said. Nassar was also a doctor for the USA Taekwondo team.

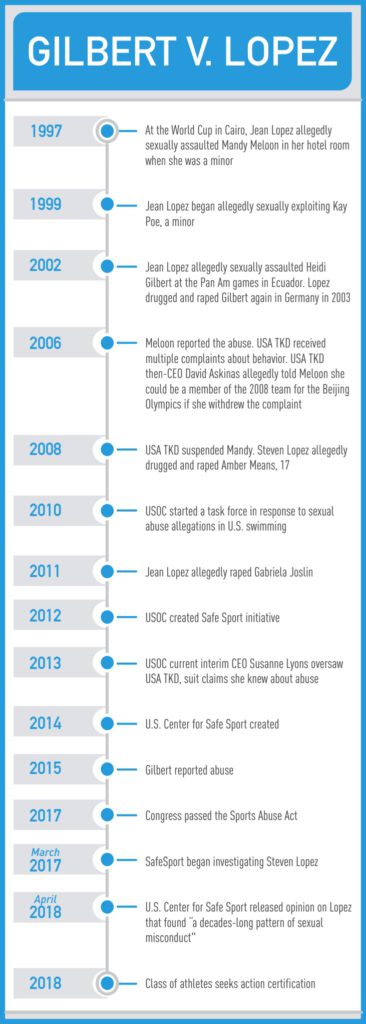

The lawsuit — brought by five former Olympic taekwondo athletes against the USOC, the USA Taekwondo Association and taekwondo coaches Jean and Steven Lopez — filed for class certification earlier this month.

Jean Lopez was the coach for USA Taekwondo in the 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016 Olympics before being permanently banned from the organization last month.

Steven Lopez, a three-time Olympic medalist with five world titles in taekwondo, was suspended May 7 after the U.S. Center For Safe Sport issued an opinion saying allegations of rape against him were found to be true. Steven faces sexual assault allegations as well, and Little said an investigation into Steven’s conduct has been ongoing since 2013.

The complaint alleges decades of sexual assault and rape perpetrated against female athletes, many of whom were minors at the time.

According to the suit, plaintiff Mandy Meloon was assaulted and raped by both Jean and Steven throughout her time as a member of the USA Taekwondo team. Meloon reported the abuse in 2006 to three USOC employees — John Rueger, Gary Johansen and then-USA Taekwondo CEO David Askinas — and pursued arbitration. Meloon wanted to compete in the 2008 Beijing Olympics with the team, but Askinas allegedly told her she couldn’t unless she “agreed to sign a statement confessing that she was mentally ill and had fabricated her allegations against Jean Lopez.” Meloon refused and was suspended. The suit states that officials received two other complaints from athletes against Jean at that time, but he was subsequently named as the head coach for the 2008 team.

Although some suits concerning Nassar’s abuse named the USOC, the Colorado lawsuit is the first to allege willful ignorance on the USOC’s part. It argues that the USOC engaged in forced labor of child athletes under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act.

Last year, Congress enacted the “Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act” as a response to abuse allegations. The act amends the TVPA and “imposes civil liability against those who commit or benefit from sex trafficking and trafficking-related offenses, especially if those actions include sexual abuse.”

The USOC called the claims “outrageous.” In a statement the organization said it intends to “vigorously defend itself:”

“We do not normally comment on active litigation. In this case though, counsel’s fantastical claims seem calculated to provoke and offend rather than to genuinely seek relief from the judicial system.

Although we have only just received this complaint, it appears to be a cynical attempt by counsel to subvert important protective laws with the goal of sensationalizing this case,” USOC spokesperson Patrick Sandusky said in a statement.

In 2010, the USOC’s website stated the organization “determined that sexual and physical abuse warranted greater attention.”

The USOC created the SafeSport Initiative in 2012 and the U.S. Center for SafeSport in 2014.

The suit argues that the organization knew of abuse and covered it up for some time and that the SafeSport Center is a method for the USOC to “gather information about their possible legal exposure,” Little said. But in its statement, the USOC pushed back on that notion, clarifying that its criticism was not directed at athletes involved in the case:

“The USOC remains focused on supporting, protecting and empowering the athletes we serve. We are aggressively exploring and implementing new ways to enhance athlete safety and prevent and respond to abuse. We have taken and are continuing to take significant actions, including the recent launch of the U.S. Center for SafeSport, to better protect our athletes from the heinous acts,” the statement reads.

University of Michigan law professor Bridgette Carr runs the human trafficking clinic at the law school. She said while it might be a stretch to make sex trafficking claims in this case, it’s not the first instance of forced labor in athletics, but people get hung up on the words “sexual abuse.”

“I don’t want to minimize sexual abuse, but sexual abuse is just a version of forced broader coercion,” she said. “Trafficking law wants to protect people who are vulnerable from people who want to exploit them for financial gain. If we think it never happens at more elite levels, then people at more elite levels aren’t vulnerable. And they are, we know they are.”

— Kaley LaQuea