A split 10th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a district court’s dismissal of a 10-year-old challenge to TABOR, but for different reasons than the lower court. For the first time, a federal court ruled on the merits of Kerr v. Polis rather than its jurisdiction, standing or justiciability.

In its latest ruling on Kerr v. Polis (formerly Kerr v. Hickenlooper), published on Dec. 13, the 10th Circuit dismissed the lawsuit for failing to state a claim upon which relief can be granted, differing from the district court, which dismissed the case for a lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

In Monday’s en banc opinion, authored by Chief Judge Timothy Tymkovich, who was joined by Judges Harris Hartz and Allison Eid, the majority of the court shifted its focus away from jurisdictional questions and instead looked at the heart of the suit: whether, under the Guarantee Clause of the U.S. Constitution, TABOR removes a “republican form of government.”

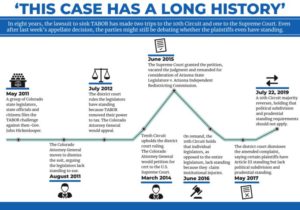

Kerr v. Polis has a long history and has moved up and down the federal appeals system since it was filed in 2011. It’s been the subject of several district court opinions, 10th Circuit opinions and en banc opinions and an order by the U.S. Supreme Court. Until now, most questions in the lawsuit have revolved around who could bring the complaint and who has the jurisdiction to hear the case.

A long list of plaintiffs, which included former and current state representatives, school boards across the state and county commissions, sued then-Governor John Hickenlooper in his official capacity in May 2011. They claimed that Colorado’s 1992 Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights prevented the state from being “a republican form of government” and violated the U.S. Constitution, the Enabling Act and the state constitution.

TABOR amended the Colorado Constitution to limit government taxation and spending. It requires that any new tax increases be approved by Colorado voters and also imposes limits on how the state government handles excess tax revenue.

According to the plaintiffs, by taking away the state government’s power to tax and handing it to the people, TABOR breaks Article IV, Section 5 of the U.S. Constitution, the Guarantee Clause, which states that the federal government “shall guarantee” every state “a republican form of government.” The lawsuit asked the courts to declare TABOR unconstitutional.

On its path up and down federal appeals courts, most questions and opinions on Kerr v. Polis revolved around if certain plaintiffs had standing. In 2014, the 10th Circuit upheld a federal district court’s dismissal of a motion by the Colorado Attorney General to throw out the lawsuit arguing the legislator-plaintiffs did not have standing to sue. The U.S. Supreme Court vacated the 10th Circuit’s ruling in June 2015 and remanded the case back for consideration under its ruling in Legislature v. Arizona State Independent Commission.

On remand from SCOTUS in June 2016, the 10th Circuit held that since the legislators claimed institutional injuries they lacked standing. A federal district court threw out an amended complaint in May 2017 and stated that the political subdivision plaintiffs (school boards, county commissions, etc.) had Article III standing but not political subdivision and prudential standing. The 10th Circuit reversed the dismissal in July 2019 and held that the political subdivision and prudential standing shouldn’t have applied.

The latest opinion comes from a request by the Governor for the 10th Circuit to hold a rehearing en banc. The 10th Circuit granted that request in October 2020 and asked the parties to file briefs arguing whether a political subdivision standing is a jurisdictional limit and what a political subdivision standing requires. In May, the 10th Circuit held oral arguments for the case.

Political Subdivision Standing: Jurisdiction vs. Merits

Monday’s opinion outlines important differences in historical and modern definitions of “political subdivision standing,” a key concept in cases where a lower government entity sues its parent state. The opinion explains the definition of “standing” evolved significantly after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Lexmark International, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc.

Notably, the court decided that its reviews needed to focus on the case’s merits rather than jurisdiction. Calling the word “standing” in political subdivision standing a misnomer, Chief Judge Tymkovich explained that “under this inquiry, we no longer ask whether a political subdivision has standing. We ask whether the political subdivision has a cause of action.”

The 10th Circuit adopted the two-step cause-of-action test established by its 2011 decision in City of Hugo v. Nichols since the zone-of-interest test laid out in Lexmark doesn’t apply to cases where political subdivisions bring claims against their parent states.

According to the majority, the federal district court correctly applied the Hugo test but did so under an incorrect procedural hearing that looked at jurisdiction rather than merit. When the case was dismissed at the request of the Governor under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12 (b)(1), lack of subject-matter jurisdiction, it should have been dismissed under 12 (b)(6), failure to state a claim, the opinion states.

“Merely because the Plaintiffs insist their claim may be stronger at some future point does not relieve them of the burden of satisfying Rule 12(b)(6),” Chief Judge Tymkovich wrote.

TABOR and the Enabling Act

The opinion went on to address the suit’s core arguments around TABOR in the constitution. The plaintiffs argued that TABOR undermines a republican form of government in Colorado; that the state constitution was adopted in accordance with the Enabling Act that created an interdependent structure between the state; and the political subdivision and that the Enabling Act recognized counties and public school districts prior to Colorado statehood.

The 10th Circuit was not compelled by any of the three arguments. It rejected the plaintiff’s interpretation that the Enabling Act is a promise of republican government and instead held that it “does not specify for whom the protection is intended or give any indication that a republican government is a right intrinsic to being a political subdivision.”

“The plaintiffs have failed to identify any source providing them with a cause of action to challenge TABOR,” reads the opinion. “Without a constitutional or statutory provision on which to hang their hat, the plaintiffs cannot state a claim on which relief can be granted.”

Judge Jerome Holmes agreed with part of the majority’s opinion, but he added that he would’ve also dismissed arguments around political subdivisions as nonjusticiable political questions and would’ve labeled it a dismissal with prejudice since the majority addressed most of the plaintiff’s claims.

Judges Robert Bacharach, Carolyn McHugh and Nancy Mortiz also agreed with most of the majority’s findings but disagreed with Chief Judge Tymkovitch’s proposal in his concurrence that he would label the dismissal as one with prejudice even though the defendants did not cross-appeal.

‘The Suit to Sink TABOR’

In its 10-year history, Kerr v. Polis was joined by parties both in support and opposition of TABOR. For those hoping to overturn TABOR, this was not the case to do so.

In an amicus brief filed by two school lobbying groups, the Colorado Association of School Boards and the Colorado Association of School Executives, the associations argued that TABOR widened school funding gaps in Colorado and consequently impacted the quality of education for students across the state.

CASB and CASE pointed out that pre-TABOR Colorado was already below the national average for money spent per student but that since its passage, the gap has nearly doubled. It also pointed out that the portion of money from personal income taxes in Colorado fell 16% between 1992 and 2010, placing Colorado 43rd in the nation for per-pupil income spending. They say that the decrease in K-12 education funding has led to poorer student education outcomes and led to 45% of Colorado school districts adopting a four-day week in 2017, nearly double what it was in 2000.

“Along with numerous academic and policy commentators, [CASB and CASE] believe that these declines have mainly been caused by TABOR,” the brief reads.

On the other side of the issue is an amicus brief filed by the public interest legal foundation Mountain States Legal Foundation, the non-profit Colorado Union of Taxpayers Foundation and the education organization TABOR Foundation. The three organizations argued that the plaintiff’s challenge “would [have] serve[d] as an intrusion upon the separation of powers and would subject Colorado taxpayers to increased taxes and larger government.”

In a statement, MSLF attorney Cody Wisneski called the 10th Circuit’s decision “a victory for the people and the taxpayers of Colorado.”