“A wholly effective system with no transparency and no public confidence will not suffice,” said a recent report on judicial discipline from the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System.

The report, “Recommendations for Judicial Discipline Systems,” serves as a guide for how the 51 judicial discipline commissions across the U.S. can be structured and what their best practices can look like.

The commissions the report addresses were first imagined in the 1960s as a reaction to scandals in state judiciaries. Before the commissions’ creation, there were few formal methods for handling a judge’s misconduct, let alone any that were efficient or well designed.

IAALS’ mission has focused on general issues of accountability for the judiciary. After reports on nominating commissions, judicial selection and judicial performance evaluations — a process it created and is now used in 17 states and the District of Columbia — the organization wanted to look at the default process of how an errant judge is removed from their position.

Before beginning research for the report, IAALS pored through available literature and found no examples of work that synthesized the best practices for judicial discipline commissions.

After nine months of research, IAALS held a “convening,” as it calls it, of 19 legal professionals representing different sectors of the legal field to discuss the best practices of disciplining judges. “It’s an opportunity for a group of stakeholders to have a candid discussion about an issue. It’s very important to our process,” said Zachariah DeMeola, a manager at IAALS.

“The real thrust [of the report] is that the commissions need to be more transparent,” said IAALS Executive Director and former Colorado Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Kourlis. “They need to explain their procedures better.”

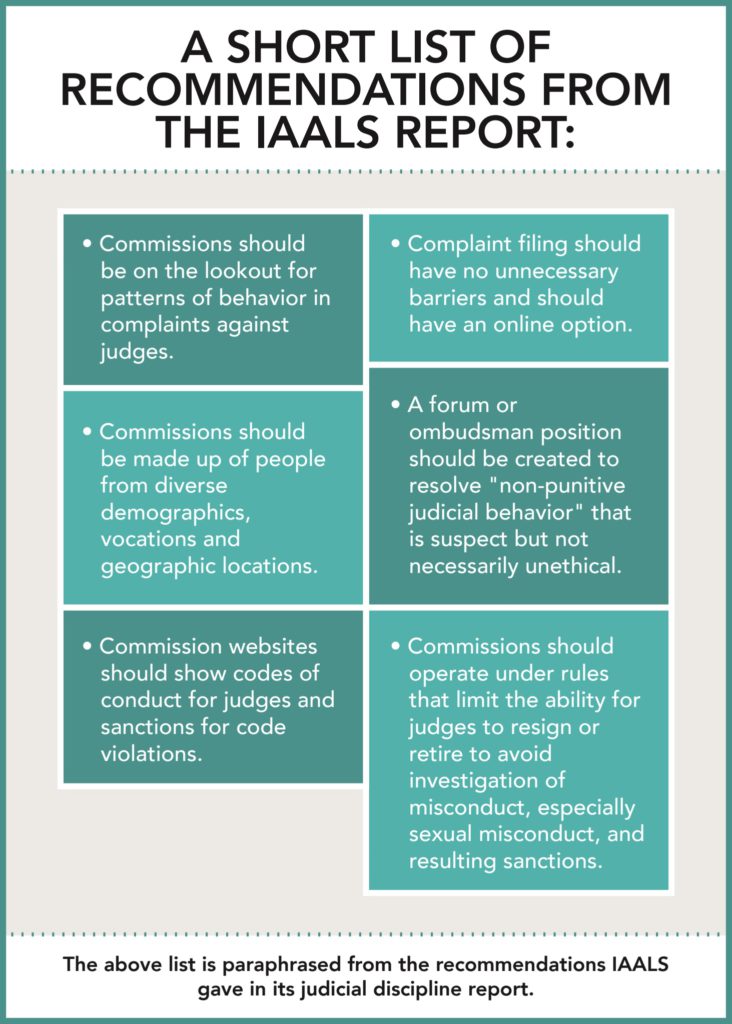

There were 15 recommendations in the report. A selection of them includes how to be impartial when investigating and adjudicating, what sanctions are appropriate and when, how to manage complaints against judges and how to share discipline orders with the public.

To be impartial around investigating and adjudicating, commissions can have a two-body structure where investigators are separated from adjudicators. Some at the IAALS meeting felt this would be unnecessarily expensive and make the process take too long.

The types of sanctions at a commission’s disposal are left to that commission’s discretion. The report encourages using remedies that fit the offense and not to overuse private remedies where the consequences aren’t shared with the public. A few states limit the commissions from being able to remove or suspend judges. The report suggests the state government reconsider that limitation.

The report says complaints against judges should be received openly with forms online with instructions in multiple languages. Requirements like notarization should be removed. States with this practice already in place note that the increase in filings is outweighed by the legibility and comprehensiveness of information in complaints as well as the reduced processing costs in dealing with less paper. Anonymous complaints are beneficial for court employees or attorneys who fear career-ending responses from judges they submitted complaints against. The report even includes that commissions shouldn’t have to wait for complaints if they find evidence of a judge’s misconduct.

In sharing results of disciplinary hearings with the public, about half of state commissions post online at least some orders from the commission or state supreme court. IAALS recommends that orders should have filtering functions when orders are posted online so that interested people don’t have to parse through orders only organized by date, case number or name of judge.

“I think as a guiding document it’s useful because it does identify those areas where state or commissioners really need to understand what is the best process for their context,” said DeMeola.

The report goes out of its way to specify that misconduct from a judge can include sexual misconduct. This is because of the #MeToo movement. “The concerns regarding MeToo sexual harassment began to bubble up and that was certainly an issue that was on our minds both in the course of the meeting and in the course of preparation of the recommendations,” Kourlis said.

She only sees change coming incrementally and hopes that state commissions they sent the report to will use it to innovate and improve their practices. She said that this project is part of a broader national effort to make judicial behavior more centered around citizens and litigants so trust in the judiciary can be developed.

— Connor Craven