A former employee at Colorado’s regulatory watchdog says the agency subjected him to a hostile work environment where he was harassed for being gay, and that it fired him in retaliation for reporting it.

Jason Purdue, who was an administrative assistant at the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies and is African American, filed a discrimination complaint Nov. 20 saying DORA suspended him, and eventually terminated him, in retaliation to a discrimination complaint he’d made earlier this year. Purdue suffered repeated harassment from coworkers based on his sexual orientation and race, which escalated into an altercation that “nearly became physical,” according to his attorney. DORA placed Purdue on administrative leave after the incident and fired him shortly after he’d returned to work. Purdue claims the agency failed to take action against his harassers and instead punished him.

“While the Division’s name might imply the existence of an environment of civility and professionalism, the reality was that Mr. Purdue was subject to, in a coworker’s words: ‘gay bashing,’” Purdue’s attorney, John Crone, said in a press release. “Unfortunately, Mr. Purdue’s complaints of this unlawful behavior went ignored, and the hostile work environment within the Division escalated.”

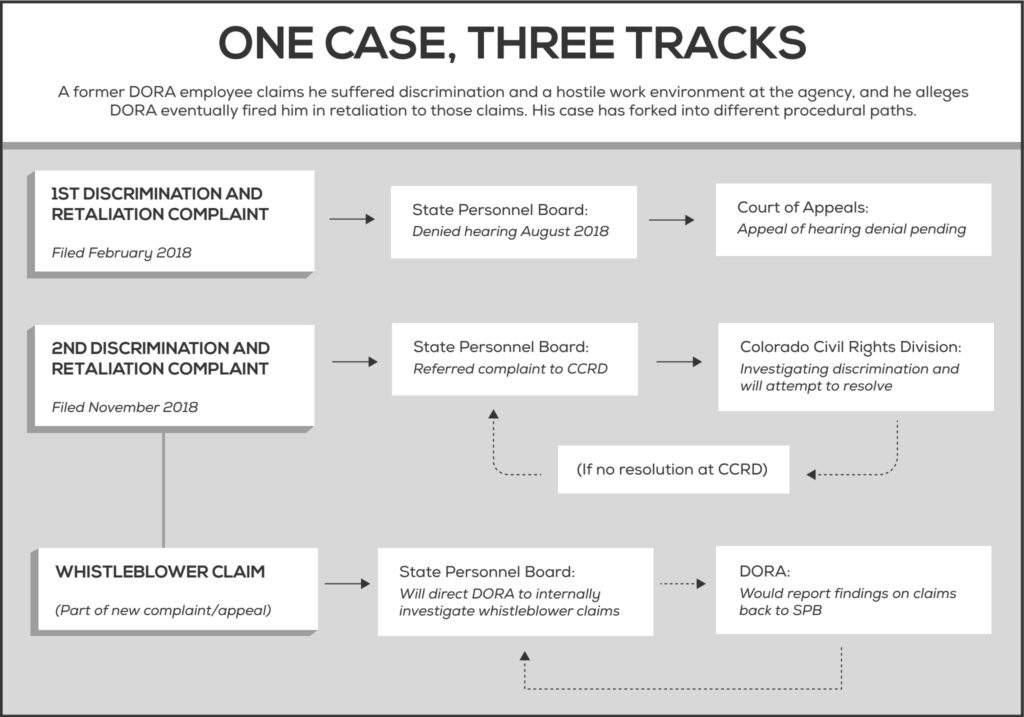

Part of Purdue’s case is currently pending at the Colorado Court of Appeals. A decision there could determine how easily administrative law judges can toss out cases that state employees bring to appeal their firing or discipline.

Meanwhile, the Colorado Civil Rights Division is currently reviewing Purdue’s new charge, which also has a whistleblower claim to be internally investigated by DORA. Crone said the “weird wandering” his client’s case must make through state agencies highlights the overcomplicated nature of the Colorado’s appeals process for state employees.

Purdue first joined DORA in October 2016. When certain coworkers learned that he was gay, they began making remarks about his sexual orientation and his race, sometimes even shouting at him, Crone said. After an incident where Purdue and his alleged harasser nearly came to blows, DORA placed Purdue on an eight-month administrative leave despite his insistence he’d done nothing wrong. On Feb. 1, Purdue filed an appeal with the State Personnel Board complaining that DORA discriminated against him and failed to take action when he’d previously reported harassment. DORA did not respond to a request for comment.

When a Colorado state employer takes an adverse action against an employee, like a termination, the employee can appeal that action to the State Personnel Board. An administrative law judge at the board then decides whether to institute a hearing for that appeal.

For his appeal, Purdue prepared evidence and had coworkers lined up to testify on his behalf, saying that he consistently tried to de-escalate the conflicts, according to Crone. But in August, the ALJ denied the hearing.

Purdue is challenging that denial at the Colorado Court of Appeals. Crone said the ALJ set an improperly high bar for Purdue to have his case heard.

The judge decided the discrimination claim failed, Crone said, because Purdue couldn’t conclusively prove it, even though discovery can only be initiated after the judge decides to grant the hearing. Instead of a standard similar to granting summary judgment, the State Personnel Board should have used a lower one similar to granting a motion to dismiss, Crone said.

The case before the Court of Appeals should elicit guidance on exactly what discretion the State Personnel Board has in granting or denying an appeal. “I think the answer right now is we don’t really know,” Crone said, adding that some case law dances on the periphery of the board’s standard, but nothing addresses it head on. “We’re asking the court to really tackle that issue.”

After Purdue returned from administrative leave in August, DORA placed him back in the environment with his harassers, and “not surprisingly this harassment continued,” Crone said.

That, plus having his appeal denied drove Purdue “down into a dark place where his mental health really suffered,” Crone said. Purdue attempted suicide, and afterward DORA’s HR director placed him on administrative leave to evaluate his fitness to return to work, according to the complaint.

On Sept. 14, the agency sent Purdue notice of a Rule 6-10 meeting, in which Colorado state employers present employees with the possibility they might face discipline or termination.

The employee must then have a chance to respond to the issues the employer raises, and after the meeting the employer makes a decision. It was after this meeting that DORA discharged Purdue on Nov. 2.

“We have a recording of that 6-10 meeting which I think is going to become critical in this case.” Crone said. “It is abundantly obvious if you listen to the meeting that they were going to terminate him from the second they issued the notice.” DORA had no interest in hearing Purdue’s side of the story or correcting the hostile work environment, Crone said.

Purdue’s new appeal, which is currently being investigated by the Colorado Civil Rights Division, has already progressed further than the one the ALJ tossed out in August.

The CCRD may either conclude that DORA likely acted unlawfully toward Purdue and try to resolve the issue through mediation or some other means. It might also fail to make a conclusion, at which point the appeal goes back to the State Personnel Board for further processing, Crone said.

Purdue is also making a whistleblower claim against the coworker he alleges is his primary harasser, saying that coworker took software from DORA. The board will refer that claim back to DORA to conduct an internal investigation.

Colorado Revised Statutes Section 24-50.5-101 forbids employers from punishing state employees who report waste, mismanagement of public funds, abuses of authority or illegal and unethical practices to a designated “whistleblower review agency” such as the state attorney general’s office.

Crone said it may take six months or longer for the new appeal and the whistleblower claim, which runs parallel to it, to “really get going.” Purdue’s opening brief for his Court of Appeals case is due January.

Before his firing, but after he filed to the Court of Appeals to challenge the ALJ decision, is when Purdue retained Crone as his attorney. Prior to that, Purdue was pro se and making his case opposite seasoned lawyers at the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, Crone said. “So he probably was outgunned, to be honest.”

State and federal employees often have more layers of due process to resolve their employment issues than private sector workers. But the irony, Crone said, is that those added layers can actually make it harder for government employees to assert their due process rights.

“The way this has evolved … is into a procedural web that’s almost a nightmare, so that state employee, or federal employee, almost can’t navigate it without attorney help. And that’s what happened to Jason Purdue in this case,” Crone said. “It’s worth asking collectively whether or not we’ve overprocessed it.”

— Doug Chartier