Two prominent, distinct narratives exist for Olympics host cities. One woven by proponents touts the growth the games can bring in the form of tourism and job opportunities. The other emerges after the closing ceremony and is told by resulting debt and photographs of decaying venues the city can’t afford to maintain or repurpose.

Denver has formed an exploratory committee to consider whether to pursue a bid for a future Olympics hosting in 2030. The committee is expected to submit a final report to Gov. John Hickenlooper and Denver Mayor Michael Hancock with recommendations to pursue a bid or not by mid-May. With the lingering memory of Dick Lamm’s successful campaign against Denver hosting the 1976 Winter Olympics, which resulted in an amendment to Colorado’s Constitution that prohibited using public money to host the Games, it seems Denver has a uniquely thorny relationship with funding options.

Although that amendment has since been rescinded, Hickenlooper told Colorado Public Radio in February a possible hosting wouldn’t use public money, a statement that echoes discussions by the exploratory committee. But as experts in Olympics economics said such a statement isn’t so black-and-white.

“It’s a talking point that bid committees in the United States feel compelled to say, because they know that taxpayers have other priorities, but it is never accurate to say that these are purely privately funded,” said Chris Dempsey, who helped lead the No Boston Olympics initiative against the city’s ultimately unsuccessful bid for the 2024 games.

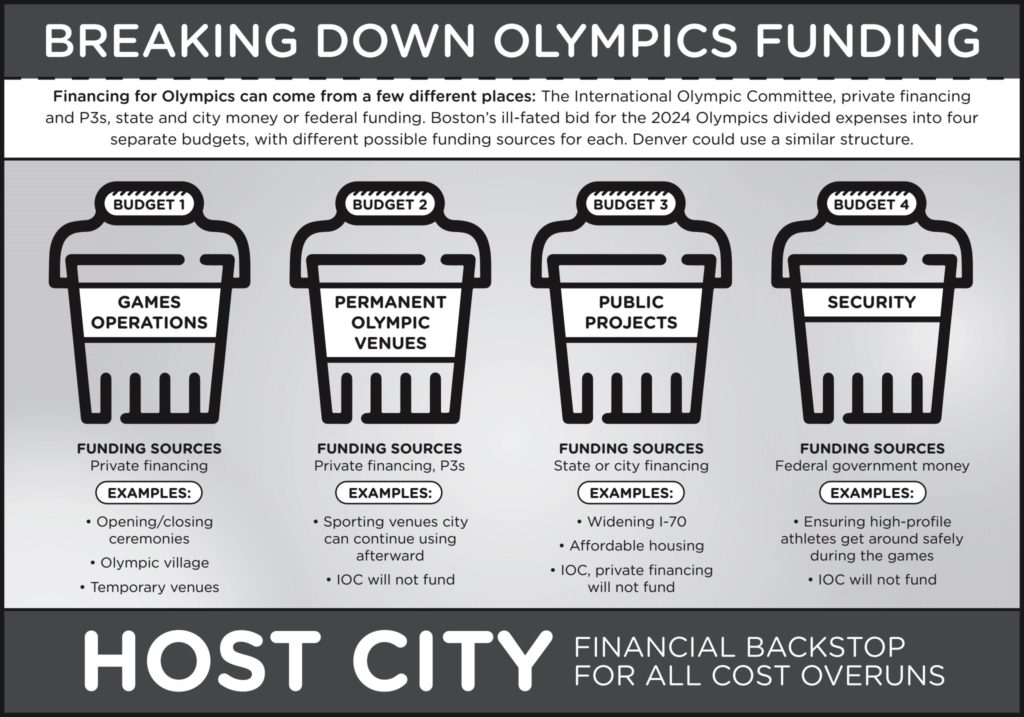

He said how Boston divided hosting expenses into four separate budgets with different possible funding sources. Denver would likely structure expenses similarly, he speculated.

The first budget included operational expenses, such as those for opening and closing ceremonies, the Olympic Village and any temporary venues. Such expenses can use private financing.

The second budget included permanent venues the city could continue using after the Olympics. The IOC will not fund such expenditures, because the hosting city receives continuous benefit from the venues, but the projects can be funded by private financing or public-private partnerships.

The third budget comprised public infrastructure projects necessary for hosting, which can include widening highways or building affordable housing. Such projects carry the expectation for public financing, Dempsey said, meaning the IOC and private backers won’t fund them. And while a city can use federal money they would have received anyway for the projects, the government won’t approve any incremental new funding for such investments when a city is awarded the Olympics.

The final budget covered security, such as ensuring high-profile athletes could travel safely around the host city during the Olympics. Dempsey said security is the only type of expense the federal government will pay for, and the IOC will not allocate funds for it.

Two things further complicate the ability to avoid using public money to host the Olympics: the IOC’s requirement for each hosting city to serve as the backstop to cover any cost overruns, and the fact that budget items can get shifted between the different classifications, Dempsey said.

“Even when a plan is put out that says this is going to be privately financed, the backstop in the case of cost overruns is the public,” he said. “And so this is why we always talk about how 100 percent of the Olympics since 1960 have had cost overruns.” He used permanent venues as an example of those that can start with plans for private funding, but if the financiers realize their original business plan won’t work, the cost overruns can pass to taxpayers.

Tom Bradley served as mayor of Los Angeles during the city’s 1984 Olympics hosting. The city was ultimately the only bidder left for those games after Tehran withdrew as a result of political changes in Iran, and Bradley did not agree to let Los Angeles serve as the public backstop for cost overruns.

“The IOC wants you to think of it as a race, where the most fit and most competitive city is going to win the race,” Dempsey said. “It’s really just an auction where the city that gives the IOC what it wants more than any other city is the one that wins.”

Dempsey said certain expenses can start as line items in the operational or permanent venue budgets that can use private funding, but sometimes get reallocated to the public infrastructure or security budgets, therefore requiring public money. He pointed to a $3 million operational expense in Boston’s bid for transportation during the games, which subsequently moved to the federally funded security budget. Dempsey said Boston’s bid committee argued high-profile athletes and IOC members would be security targets and the federal government should cover the expenses to keep them safe.

“That’s emblematic of what happens with Olympic budgets really almost anywhere they’re put on,” he said. “The things that are a cost in the first few buckets end up getting pushed to the others.” Dempsey added he believes Denver and Colorado would likely find itself in a similar situation should the city pursue a bid, for which current operating expense estimations sit at around $2 billion.

Attorney members of Denver’s exploratory committee did not comment for this story following multiple requests from Law Week.

Not a Simple Question

Opponents of Denver playing Olympics host are currently drafting a possible ballot initiative to give state and city voters a say in whether Denver pursues a bid. Larry Ambrose, a law professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver who is involved in the drafting process, said the exact language of any initiatives is still being worked out because it isn’t as simple as asking voters whether they want to host the Olympics. But the measures would hinge on whether to spend public funds doing so.

“How you phrase that is important,” Ambrose said. “You cannot pose an administrative question to the voters. It has to be legislative in nature.” That distinction is addressed in case law, he explained, but generally speaking, voter initiatives can’t control the executive branch of government.

Although the changes concerning public financing for Olympics hosting voted into Colorado’s Constitution in 1972 have since been rescinded, the Taxpayer Bill of Rights would still require voter approval for public money used to host. Developer Kyle Zeppelin, a co-chair of the NOlympics Colorado Committee, said he believes TABOR does provide an extra measure of protection for voters.

But the statute narrowly defines the scope public funds, and spending on projects that could have any feasible purpose outside the Olympics could be counted outside a budget for the Games.

“Our thought is to get it on a ballot in a form that prevents them from using public funds, basically taking them up on all these statements that they’ve made,” Zeppelin said. “If they’re so sure of themselves they shouldn’t have a problem having that codified.”

Dempsey said boosters and politicians supporting Boston’s 2024 bid also claimed hosting would not use public funds, beginning in 2013. They can say the Olympics simply accelerate certain public infrastructure projects a city would invest in anyway or say the statement “no public money” only included no local or state taxpayer funds and not the required federal funds for certain expenses. Denver’s exploratory committee is also examining options to set up a special-purpose district or tax-exempt entity in order to hold and spend hosting funds for the games.

Bidding cities will also often tout cost overrun insurance as a measure of protection for taxpayers. But as Dempsey said, although such insurance may cover unexpected, uncontrollable overruns, it would not cover voluntary over-budget spending by a planning committee.

He used the example of a stadium built for the 2012 London Olympics that financiers originally planned to downsize for subsequent use, but ended up spending extra money to repurpose the venue into a 50,000-person soccer stadium. Such expenses would not fall under the coverage of cost overrun insurance.

“If you have a perfectly [designed] building, and you look like you have all the blueprints done and all the engineering plans done and you are then going out to get a general contractor to build that very specific building for you, you can buy cost overrun insurance for that,” he said. “The insurance company is going to cover the specific things that the contractor is legally obligated to do. It’s not going to give you insurance if you decide to add five more floors to the building.”

—Julia Cardi