A federal appeals court in New York released a revised opinion Tuesday in a copyright case involving a photograph of the late pop star Prince. The court ruled that a recent Supreme Court decision did not give the late artist Andy Warhol the right to copy the photograph for a series of drawings.

The case arose out of images obtained by the photographer Lynn Goldsmith on Dec. 2 and Dec. 3, 1981 as part of an assignment for Newsweek. The late Andy Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create a set of paintings and drawings, but he was licensed only to use the photo to create one image to be published in a popular magazine.

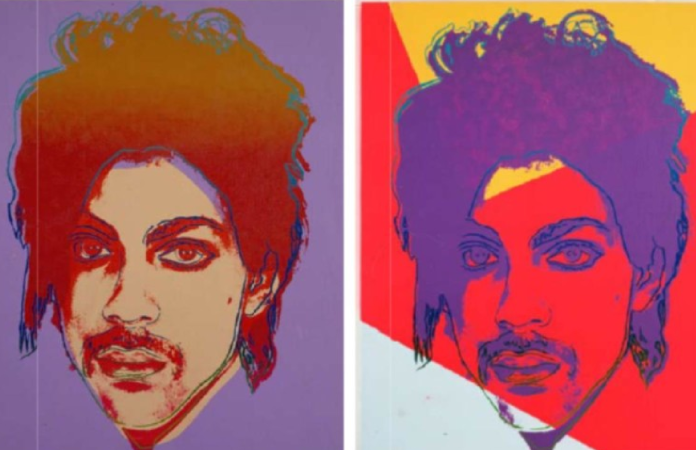

“There’s a photo of Prince and there’s the Andy Warhol version of it,” said Michael Dulin, a partner and intellectual property lawyer at Polsinelli.

Goldsmith took photos of Prince at both a New York concert and in her studio. The studio photos were never published. Instead, Goldsmith’s agency licensed one of them to Vanity Fair “for use as an artist reference in connection with an article to be published,” a purpose that Goldsmith herself did not know about, in exchange for $400. Vanity Fair — then and now owned by Condé Nast, Inc. — did not tell Goldsmith or her agency that the artist was Warhol, who used Goldsmith’s photo to create a single image that accompanied a Nov. 1984 article about Prince.

Warhol later created the “Prince Series,” a set of 15 other depictions, and then sold 12 of the originals and numerous copies of them. The Prince Series included 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil drawings. Goldsmith did not know that Warhol used her photo to make the Prince Series until Vanity Fair published a magazine tribute to the singer shortly after his death in April 2016. Goldsmith, who never saw any of the Prince Series works, told the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc., which licensed publication of Prince Series images, that she thought Vanity Fair’s cover depiction of Prince on the tribute periodical was copyright infringement. She proceeded to register her copyright of the 1981 photograph licensed to Condé Nast.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., an entity that inherited Warhol’s multi-million dollar estate, sued Goldsmith, asking for a declaratory judgment that none of the Prince Series works was an infringement of Goldsmith’s copyright. Goldsmith then sued AWFVA, alleging that both Warhol and AWFVA infringed her copyright of the Prince photo in numerous ways. Her lawsuit focused mostly on the foundation’s license of a Prince Series work she claimed was based on it to Condé Nast for the 2016 tribute periodical.

U.S. District Judge John Koetl of Manhattan ruled July 1, 2019 that Warhol’s use of the photo was a “fair use” under federal copyright law. After listing the four factors courts use to decide whether fair use exists, Koetl focused on the “purpose and character of the use.” “The most important consideration” relevant to that factor, he said, is “the transformative nature of the work at issue.” Quoting a 1994 Supreme Court decision, Koetl explained that the key question is “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.”

The judge then determined that, because Warhol’s Prince Series was “commercial in nature,” “add value to the broader public interest,” and “can reasonably be perceived to reflect” qualities different from those Goldsmith said she emphasized in her photograph, his work was transformative of that image. “The Prince Series can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” Koetl wrote. “The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince – in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

Koetl concluded that Warhol “removed nearly all [of] the [Goldsmith] photograph’s protectable elements,” that the Prince Series images “are not market substitutes that have harmed — or have the potential to harm — Goldsmith,” and that, while the Goldsmith photograph was obscure – a fact that would ordinarily be a consideration that favored the photographer – relative lack of public awareness of it was “of limited importance because the Prince Series works are transformative works.”

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Koetl’s conclusion. In a March opinion, Judge Gerard Lynch first addressed the reach of a 2013 decision by the 2nd Circuit that guided Koetl’s decision. Describing that case, known as Cariou v. Prince, as “the high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works” and acknowledging that it “has not been immune from criticism,” Lynch emphasized that “fair use is a context-sensitive inquiry that does not lend itself to simple bright-line rules.” Koetl, he said, “read Cariou as having announced such a rule, to wit, that any secondary work is necessarily transformative as a matter of law if looking at the works side-by-side, the secondary work has a different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with distinct creative and communicative results.” That, Lynch said “stretches the decision too far.”

Instead, Lynch continued, courts should not assume that “any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative.” In other words, according to Dulin, “you can’t just impose your own artistic style on another recognizable work.” Lynch, who is also a professor at Columbia Law School, analogized the situation involving Goldsmith’s photograph and the Prince Series to a film adaptation of a novel. “Such adaptations frequently add quite a bit to their source material: characters are combined, eliminated, or created out of thin air; plot elements are simplified or eliminated; new scenes are added; the moral or political implications of the original work may be eliminated or even reversed, or plot and character elements altered to create such implications where the original text eschewed such matters.” As a result, movies based on fiction or nonfiction works are generally considered protectable derivative works.

Lynch said that, unlike the situation of a film adaptation of a fiction or nonfiction work, there was not enough difference between the purposes of Goldsmith’s photo and those of the Prince Series. Warhol’s works, he said, “are much closer to presenting the same work in a different form, that form being a high-contrast screenprint, than they are to being works that make a transformative use of the original.” “[T]he Prince Series retains the essential elements of its source material, and Warhol’s modifications serve chiefly to magnify some elements of that material and minimize others,” Lynch continued.

The 2nd Circuit panel warned against a focus on the alleged infringer’s possible or actual artistic desire. “Though it may well have been Goldsmith’s subjective intent to portray Prince as a vulnerable human being and Warhol’s to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon, whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic — or for that matter, a judge — draws from the work,” Lynch wrote. “Were it otherwise, the law may well recognize any alteration as transformative.”

Lynch, a federal judge since 2000, explained that courts should take care not to “assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.” By doing so, he continued, judges might betray the reality that they “are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments” and may run the risk of basing decisions on “perceptions [that] are inherently subjective.” Kate Lucas, a senior associate and an art lawyer at New York’s Grossman LLP, said the 2nd Circuit panel was acknowledging that evaluations of artistic intent are unstable ground for copyright decision-making. “[An artist can post-hoc rationalize,” she said. “They talk about the idea of purpose being a little bit slippery when it comes to visual art.”

After evaluating the other three fair use factors, the appeals court panel ruled that, as a matter of law, Goldsmith’s copyright was infringed by the Prince Series.

One question left open by the 2nd Circuit decision is the impact the court’s cropping of the transformativity doctrine will have on visual artists. “[T]hey talk about how they’re much more comfortable as a fair use matter with works that incorporate a lot of different sources instead of just one,” Lucas said. “You can think of a collage piece that incorporates images from many other sources being in this panel’s view safer, as a fair use matter, than a work that uses as its centerpiece a single work like the Goldsmith photo. You can start to see how the law is expressing not a preference, but that some types of art are safer than others.”

Another looming issue in the aftermath of the Goldsmith case is its impact on artists working in other genres. “On the one hand, you’re telling us, ‘no, you should be careful about that’ and, on the other hand, you are using these analogies to other fields, to other mediums, to other forms,” Lucas said. “It’s hard to say with any certainty what this means for a musician or a filmmaker or a choreographer.”

AWFVA has the option of asking the Supreme Court to grant certiorari in the case. Lucas is unsure whether at least four of the justices will be sufficiently interested in the dispute to do so. “Do we essentially need two different bodies of case law regarding fair use and transformativity, one for art with a capital A and the other for tech and these more computer and coding and technology and functional iterations of fair use?” she said. “That’s a tricky question. I don’t know if that [legal conversation] is fully developed yet.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Quotes have been edited for clarity.