The traditional route for people accused of a crime typically involves an arraignment, finding or being assigned a lawyer and either fighting for your innocence in front of a jury of your peers or accepting a plea bargain from prosecutors.

But some people accused of a crime will never take that road. Instead, they’ll take part in a diversion program. Who participates in diversion programs differs across the state and sometimes differs between district attorneys.

Broadly, the Criminal Justice Program Unit of the Colorado Judicial Branch told Law Week via email that the considerations on eligibility include the level of charge, local resources, history of criminal involvement and the accountability of the participant.

One of the oldest diversion programs in Colorado is in the 17th Judicial District, headed by District Attorney Brian Mason.

Mason said that the diversion program allows him to identify people who have committed crimes, typically lower level ones, and keep them out of the criminal justice system entirely. Some of that criteria includes not having a lengthy criminal history or not having committed a violent crime.

When the criteria is met and Mason and his team view it in the best interest of the community to keep that person out of the criminal justice system, they put them in diversion.

Benita Martin, director of the Denver District Attorney’s Office Diversion Program, told Law Week that the office has had a diversion program for juveniles dating back to the 1970s and launched an adult diversion program in 2018.

When Martin and the Denver office launched the program, they started with the 18-26-year-old age range, and with only felony offenses.

“A lot of programs may, I’m not talking about Colorado, but I think in general, they may want to start small and start with maybe some misdemeanor offenses,” said Martin. “But it was just that mentality, go big or go home.”

Since its launch six years ago, they were able to secure more funding and hire additional diversion officers, which allowed them to expand the program. Martin said the expansion was initially up to the 18-30-year-old age range, and then to adults of all ages.

How Diversion Works

Every day, Martin reviews the docket of everyone that is arrested in Denver. She and her team then read the cases, pull out potentially eligible cases and then determine the likelihood of conviction for the case within a two week timespan.

Once the diversion team establishes that, they offer the diversion option to the defendants at second advisement, which Martin noted was generally around two weeks later. If they agree to participate, they have an option of securing an attorney. Then an intake is scheduled, where Martin’s team does a few risk assessments.

“We want to not only address their risks, but we want to address their specific needs,” said Martin.

In the 17th Judicial District, the process for diversion referral is similar.

When Mason, diversion director Ann Padilla-Parras and the team review the docket, they identify people who meet their criteria, like not having a lengthy criminal history or not having committed a crime.

The 17th Judicial District also completes an assessment when each client comes in. Padilla-Parras told Law Week that each case plan is individualized to the client.

“We go through something called risk, needs, responsivity, and that’s really just focusing on their risk level,” said Padilla-Parras. “That can be high-risk, moderate-risk or low-risk, and each client will have to see their client manager based on their risk level.”

After the assessment, Padilla-Parras said they want to connect clients with community treatment resources.

“We want to stay in our lane and make sure that we’re dealing with the risk that got them to our program, but also supporting them in the community, so that when something else comes up during life, that they can go to their community resources,” said Padilla-Parras.

Some examples for treatment she gave included cognitive behavioral therapy, counseling, anger management groups and restorative justice work.

In Denver, Martin noted that she and her team use a tool called the service planning instrument, which helps them identify some of their clients’ top risk areas in order to address their needs.

While programs and services are in place to address the criminogenic risk factor, Martin said they also know that some of their clients need mental health or substance treatment services.

“We have a plethora of treatment providers that we’re referring clients out to for either mental health support or substance support, or sometimes both if they have co-occurring disorders, and we want to address that as well.”

A High Success Rate Across Colorado

“We had a case not too long ago where some kids had been throwing rocks at a moving train, and the rocks struck the train,” said Mason. The conductor had to bring the train to an emergency stop and the rocks broke some of the train’s glass windows. “It wasn’t catastrophic, but it could have been, and these were kids. They were juveniles who were throwing rocks and they shouldn’t have, yet these were not hardened criminals.”

In this case, Mason said the office made the decision to put them in diversion. The office worked with the railroad company, and the kids did restorative justice work with the company, including apologizing. The kids also went out into the community and talked to other kids at schools about why you shouldn’t throw rocks at trains, Mason explained. He noted the kids completed the program and didn’t commit another crime.

According to Mason, that case is not an isolated success. He said the percentage of people who pass through the district’s diversion program and don’t commit any other crimes for at least three years is close to 90 or 95%.

“I wish that every program had a 90% success rate,” said Mason. “It’s amazing and it, for me, affirms the investment that we have put into diversion.”

Mason has overseen a significant expansion to the district’s diversion program, with diversion cases up 60% over the last three and a half years. Padilla-Parras said the number of cases in diversion went from around 250 to about 600.

Mason told Law Week that this expansion is paying dividends with clients succeeding in the program and never committing another crime.

“I think it’s successful because we’re addressing the core fundamental reasons why they committed a crime in the first place and investing in rehabilitating them,” said Mason. “And they invest as well, because they have to, if they don’t invest in the program, then they’re going to get charged with a crime. So the folks who decide that they want to turn their lives around invest in this program to the same degree that we’re investing in them.”

In addition to investing in the program, Mason noted that the people in the diversion program have to take accountability for what they’ve done. If someone doesn’t take accountability, they don’t get accepted into the program and need to pursue their case in court.

Across the county border, Martin is seeing a similarly high success rate. Denver’s team measured recidivism at one year and 96% of the 140 clients who successfully completed the program didn’t commit another crime. While some clients did exit during the program, the success rate was still 88% for those that entered the diversion program.

One successful case that Martin highlighted happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The client that came in was a young man who was a heavy meth user. She said it was challenging for him to get to the program.

But they were able to get him treatment, and he recently reached out to Martin thanking her for entering him into the program and asking for a successful program termination letter so he could start a high paying job.

Part of that success comes from building a case plan with them, rather than for them. Martin noted that when people first come in after being charged, there’s a lot of shame and embarrassment.

“We make it our business when a person first comes in — yes we have to talk about the case initially — but after that, it’s all about support,” said Martin. “We understand what you did, but that doesn’t mean that this is the end of your life, and this doesn’t mean that you can’t recover from this.”

All Denver clients take a StrengthsFinder assessment, where their top five strengths are identified and incorporated into their case plan with them.

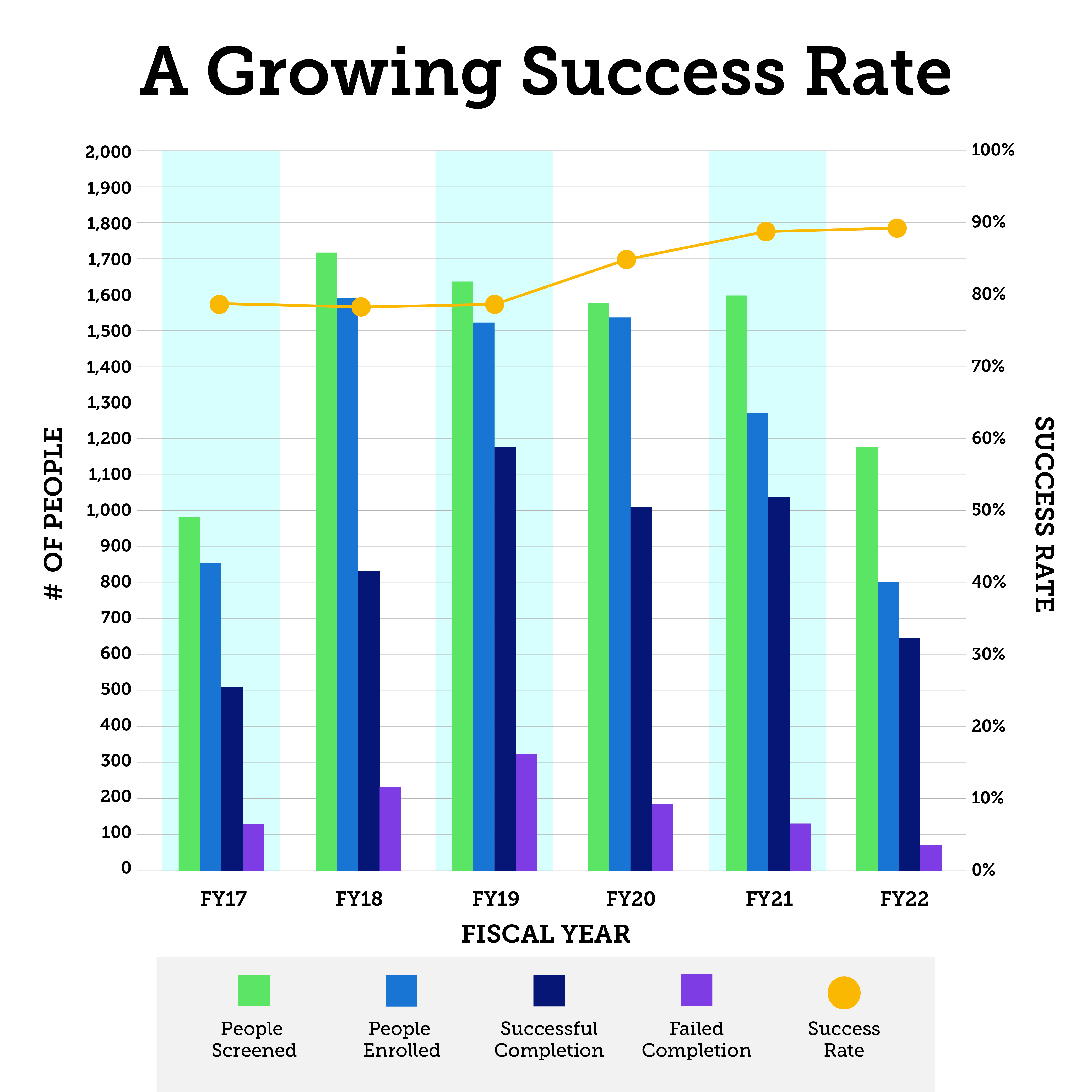

The success rate across the state is also high, and has grown over the last several years, according to data compiled from CJPU.

While the CJPU doesn’t have data for all of the judicial districts, the success rate for the districts it covers is 88%. That rate includes participants who successfully completed the program, avoiding convictions and the associated consequences.

Funding Challenges

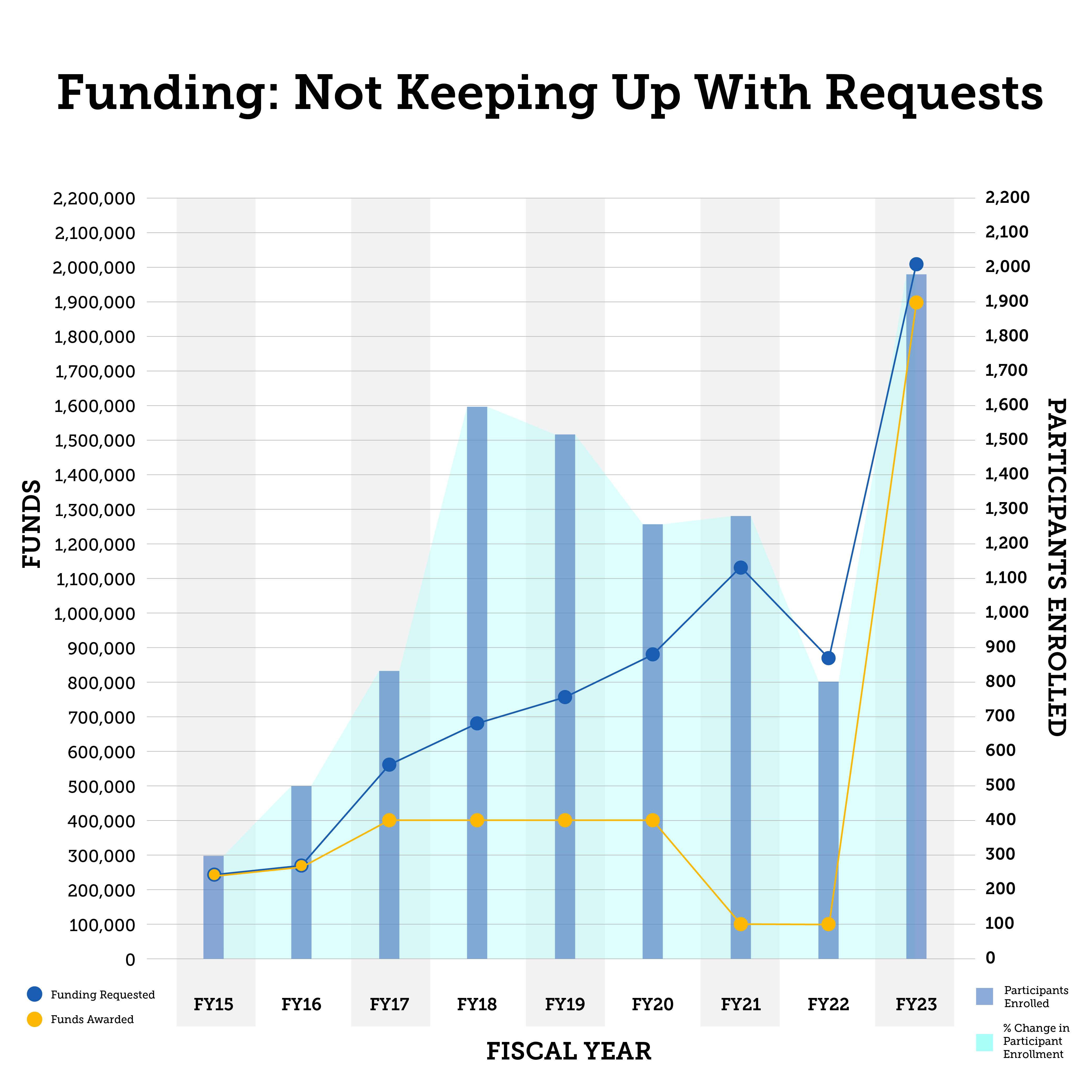

CJPU noted that the potential for the adult diversion program is undeniable, but inconsistent funding limits its impact.

In fiscal year 2023, the program received a significant funding injection from the American Rescue Plan Act and Correctional Treatment Funds, which led to the participation of 13 judicial districts, compared to just four previously.

The data provided by the CJPU showed a 33% growth in enrollment in that year, reaching 1,985 participants, along with more than $207,000 paid in restitution to victims.

In contrast, funding reductions in fiscal 2021 and 2022 led to a 75% decrease in participant enrollment. Uncertainty also remains over the program’s future, with the expiration of ARPA funds coming in June 2025, after the expiration date was extended from December.

CJPU explained lack of funding more heavily impacts rural programs and casts a shadow of uncertainty over the program’s future.

Martin said that funding is often a big barrier and a hurdle at times, and the grant funds they receive aren’t always sustained. She noted that if there was steady funding from the state for diversion programs, she would be more confident and comfortable in expanding Denver’s diversion programs.

Mason told Law Week that he was lucky to have the funding in his district for the diversion programs.

“I don’t know a single elected district attorney in Colorado that doesn’t want to have a large diversion program in their judicial districts, but the funding doesn’t exist in every judicial district to do that, particularly the rural ones,” said Mason. “I encourage our state legislators to really tackle this problem and to provide funding, particularly for those jurisdictions that don’t have it themselves.”