As President Joe Biden seeks to fill more than a dozen seats on federal appeals courts, he is showing a willingness to appoint judges who have a more varied array of professional experiences than did his immediate predecessor and other recent chief executives. Biden also demonstrated his intention to assure a more demographically diverse judiciary.

Since taking office, the 46th president has nominated 24 federal judges, including seven candidates for the appellate courts. Twenty-one of Biden’s nominees thus far are women, a total that exceeds the number of female judicial nominees proposed by former President Donald Trump throughout his entire term. More than three-fourths of Trump’s judicial nominees were male, while more than 84% were white, according to the American Constitution Society. For the 13 circuit courts of appeal in particular, both gender and racial diversity are lacking. ACS estimates that 76.6% of appellate judges are white and 64.9% are male, while the American population is about 72% white and 48.9% are male.

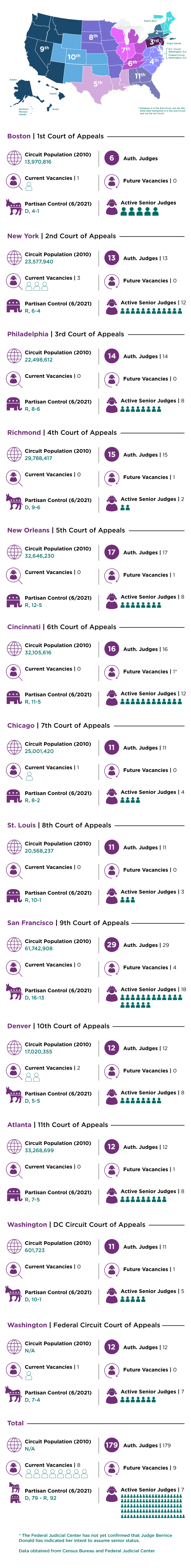

According to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, there are now 14 current or future vacancies on federal appeals courts. The first of Biden’s nominees to fill them — Ketanji Brown Jackson of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit — was confirmed on June 14, while the second, Candace Jackson-Akiwumi, a nominee to sit on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, was confirmed Thursday. Four others

— Tiffany Cunningham, a Chicago-based patent lawyer nominated to take the place of Judge Evan Wallach on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit; Gustavo Gelpi, Jr., who would replace the late Juan Torruella on the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals; Eunice Lee, a nominee to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals who would replace the late Robert Katzmann; and Veronica Rossman, nominated to replace Judge Carlos Lucero on the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, have already had confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

One other nominee is awaiting committee hearings: Myrna Perez, selected to fill the seat formerly held by Judge Denny Chin on the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The White House has not announced nominees for a second opening on the 2nd Circuit or a second opening on the 10th Circuit.

Female nominees are not the only obvious feature of Biden’s selection list for the federal appeals court bench. The candidates for those positions also reflect both ethnic and professional diversity to an extent that has been uncommon in recent presidencies. Four of them — Cunningham, Jackson, Jackson-Akiwumi, and Lee — are Black women, while two others — Gelpi and Perez — are of Hispanic descent, one — Rossman — is an immigrant and the recipient of asylum status, and five — Gelpi, Jackson, Jackson-Akiwumi, Lee, and Rossman – worked in the federal public defender system.

One challenge that University of Florida Levin College of Law Professor Danaya Wright thinks Biden should keep in mind is balancing the importance of sufficient experience in law practice of any sort with the imperative of broadening the population of lawyers or state and lower federal court judges who are considered for appointment to the federal circuit courts of appeal. “I do think it’s too small of a universe,” she said, pointing to a recent pattern of appointing former Supreme Court law clerks as justices.

Professor Joshua Kastenberg of the University of New Mexico School of Law and a former U.S. Air Force prosecutor and military judge thinks that experience representing criminal defendants is a particularly necessary asset of federal judges. “One is, it brings fairness to the court,” he said. “The other thing it does is it brings a unique experience to the courts – to understand what really goes on in the courtroom.” Kastenberg explained that appointing lawyers who represented individuals charged with crimes also honors American history and the traditional view that such work is worthy of acclaim.

“I go back to our nation’s beginning, even before the Revolution,” he said. “John Adams represented British soldiers who were accused of a massacre in Boston. I think that’s an important point to make because, for many years, there was no nobler profession.” Kastenberg explained that, until recently, presidents of both parties did not hesitate to put former criminal defense lawyers on the bench. That changed as partisan battles over the courts grew more intense, he said. “In my lifetime, public defenders have been vilified.”

Kastenberg noted that law firm partners, who are frequent recipients of appellate judgeships, tend to be relatively inexperienced at managing trials. This represents a gap in their backgrounds and can limit their ability as appellate jurists to recognize legally significant flaws in those proceedings.

“They don’t particularly litigate,” Kastenberg said, referring to law firm partners. “They may be on a litigation team, but litigation to a large law firm is actually the art of preventing going to court. So you do a lot of paperwork in the transactional sense and you try to settle cases or you try to defeat the other side through finding means to not provide discovery to them.” Kastenberg said that presidential reliance on law firms for prospective judges is also problematic for two other reasons: homogeneity and prevailing attitudes about access to justice. “They still tend to be overwhelmingly white and male,” he said, referring to law firm membership. “And they also tend to have a jurisprudence [that would] minimize the ability of the average American to get into a courtroom, either through doctrines of standing or through [hostility to] class action cases.”

Prosecutors, especially those who spent their careers in the Department of Justice, may be unlikely to actually try cases very often. In their instance, Kastenberg said, it’s because plea bargains often resolve cases. “Sure, former prosecutors sitting on the bench will have significant litigation experience if they’ve been state prosecutors,” he said. “But my mentor years ago, who was an assistant U.S. attorney, went 14 years between cases that actually were fully litigated in front of a jury.”

Those flaws in recent presidents’ selection habits also limit the demographic diversity of the federal appeals courts, Kastenberg said. “This fixation on clerking for Supreme Court justices and also sort of this elitism in the law, which has heavily favored white men for so many years, shuts the door on people who actually know how the law works.” Wright explained that the varied experiences of lawyers who have not spent their careers in corporate law firms or prosecutors’ offices are crucial if appellate judges are to gain a “proper understanding of how these laws actually function in people’s lives.” Not only that, but professional tribulations seem to her to “affect the decisions that people write.” “They affect how we interpret rules,” she said. For the public, judges’ backgrounds can lead to the preparation of diverse opinions that are similarly compelling and persuasive. “

Wright remarked that, in her experience, it is not unusual to read a majority opinion and a dissent in a particular case and find that they are both convincing. “They’re both right.” she said. “Both opinions are plausible, even though they come to completely opposite conclusions. The only way, I think, to validly and morally choose which is better is to look at the effect these decisions have on different groups of people,” she said. “Unless you have judges with different lifetime experiences,” Wright continued, “you’re not going to get a proper understanding of how these laws actually function in people’s lives.” “That’s what matters,” she concluded. “That’s what the law is about.”

For that reason, academics tend to make good appellate judges. “They bring a scholarship with them and the desire often is the desire to do a deeper dive into an understanding [of] how today’s ruling may affect tomorrow’s potential plaintiffs or defendants,” Kastenberg said. The problem for legal scholars, he said, is that their academic work can be exaggerated into alleged controversy when they are nominated for a judgeship and must face senators at a committee hearing. “They often write cutting edge ideas in the law reviews and the like,” Kastenberg continued. “And once those are presented before the Senate Judiciary Committee, they’re picked apart.”

Beyond the diversity of federal judges, Wright said Biden should prioritize an effort to expand their number. “We should add more seats on these circuits,” she said. “We should probably have a couple of additional circuits. It’s so difficult to get a case up to the Supreme Court. So much is happening at the court of appeals level and we don’t have enough judges.” The current authorized number of federal appeals court judges is 179, a number that has not changed since 1990. Since then the nation’s population has grown from about 249 million to at least 330 million, an increase of at least 33%, according to the Census Bureau. Filings in the appeals courts increased by 40% between 1990 and 2016, with the caseload per average three-judge panel rising from 773 in 1991 to 1,084 during the same period, according to 2018 testimony before a House Judiciary Subcommittee by three federal judges representing the Committee on Judicial Resources of the Judicial Conference of the U.S.

In 2019 the Judicial Conference of the U.S. asked Congress for five additional appeals court judges, suggesting that all of them be assigned to the 9th Circuit. Congress, despite having passed seven bills to expand the federal courts between 1960 and 1990, has not made any significant effort to do so again during the past 30 years. The three-decade lull in the expansion of the appeals courts is the longest since they were established in 1891, according to the Congressional Research Service.

As for the number of federal circuits, Congress has long debated whether to split the vast 9th Circuit, which covers seven states in the expansive far west plus Alaska, Hawai’i, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Kastenberg thinks it unlikely that any bill proposing that action will get far. “The problem with splitting the 9th Circuit is that when a Republican president is in office, that’s when the Republicans want to split it,” he said. “When a Democratic president is in office, that’s when the Democrats want to split it.”