In what’s been called an “uncommon” partnership, a prosecutor and a criminal defender are working together to promote a process that’s been said to help heal victims and offenders and help reduce recidivism.

On July 31, the Colorado State Public Defender’s Office and the Denver District Attorney’s Office agreed to collaborate on a project to expand the use of restorative justice practices throughout Colorado. The program, launched with the help of the Colorado Restorative Justice Council, will have attorneys from the offices developing a road map of best practices that all communities and court systems in the state can follow in using restorative procedures.

Restorative justice, which Colorado statute defines as practices that “emphasize repairing the harm to the victim and the community caused by criminal acts,” can take many forms. Oftentimes it consists of meetings or dialogues between the victim or survivor of a crime and the person who committed it, facilitated by community members who are trained to do so. In the process, which is voluntary for each side, the offender is supposed to accept responsibility for the harm he or she caused and commit to some sort of resolution, which could include an apology, community service, counseling or other remedies. In restorative justice, the process often aims for the offender’s rehabilitation rather than incarceration. It’s most widely used in juvenile cases but is seeing implementation in some adult cases.

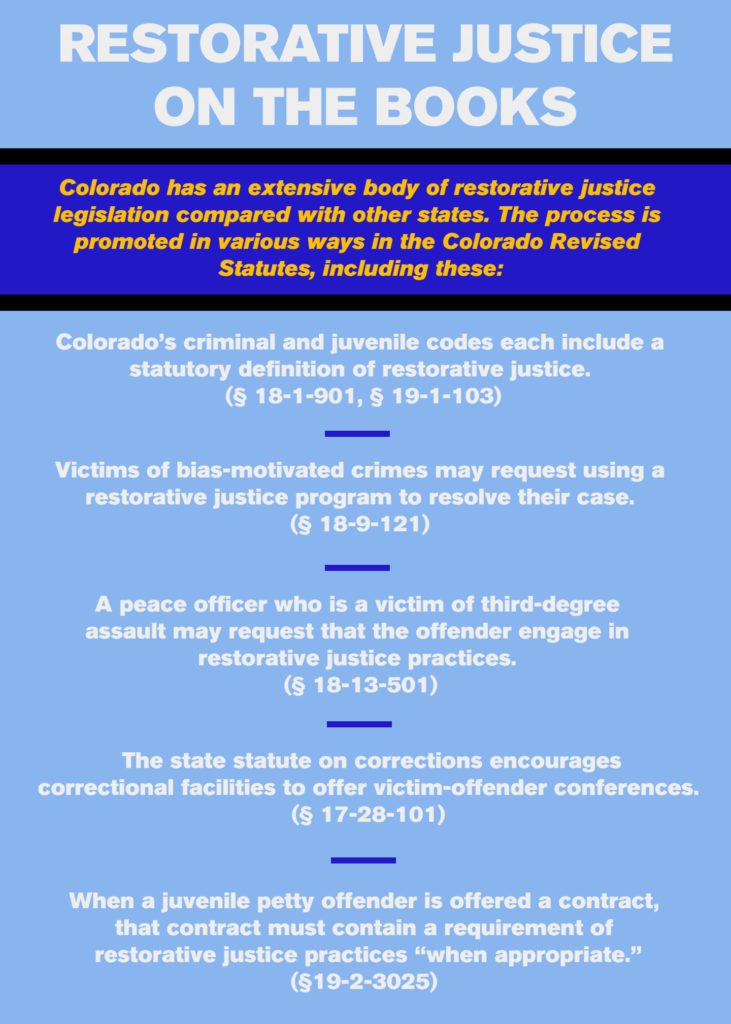

Compared with other states, Colorado has been progressive in promoting and even codifying RJ practices in legal cases. In 2007, the state legislature enacted a bill that created the Colorado Restorative Justice Council, and since then the state passed laws to promote restorative practices in more than 35 different statutes. Colorado wrapped up pilot projects in 2016 that analyzed the costs and benefits of RJ practices in four judicial districts.

Criminal justice systems along the Front Range, like Boulder and Denver, have made strides in using restorative practices in the past decade, but there’s more room for RJ to grow in the state, according to Colorado RJ Council Chair Melissa Westover.

“I think we’re doing really well, and I’d like to see us go even further,” Westover said.

The council helped coordinate the partnership between the Denver DA’s Office and the Public Defender. The agreement, Westover said, “makes a statement in and of itself” on how the restorative practices can be mutually beneficial. “Seeing that both of these entities see restorative justice as a viable option for both victims and offenders, and want to look for opportunities to implement restorative programming, is pretty remarkable.”

Under the agreement, each office will dedicate an attorney to analyze data on RJ procedures, come up with best practices and curriculum for implementing them in Colorado, and present their findings and provide training to communities throughout out the state. Senior deputy state public defender Liz Porter-Merrill and chief deputy district attorney Michael Song will work together and spearhead the project.

Denver District Attorney Beth McCann said it’s “uncommon” for prosecutors and defenders to have a formal partnership quite like this. But she said her office has “a pretty good relationship with the public defender’s office here in Denver,” and neither is a stranger to RJ practices.

“As a general rule, the criminal defense bar is very supportive of restorative justice as an alternative to the criminal justice system,” said Maureen Cain, policy director for the Colorado Criminal Defense Institute. Many victims as well as defendants are often “dissatisfied” with the adversarial system in their cases and might benefit from an alternative process, she added.

In one example she’s seen of restorative practices post-conviction, Cain said a juvenile, who was sentenced to life without parole for murder, had met with his victim’s parents in prison. The parents said the dialogue was “one of the most powerful things that has happened to them,” she said, and that the convict and the father still have an ongoing correspondence.

In one example she’s seen of restorative practices post-conviction, Cain said a juvenile, who was sentenced to life without parole for murder, had met with his victim’s parents in prison. The parents said the dialogue was “one of the most powerful things that has happened to them,” she said, and that the convict and the father still have an ongoing correspondence.

One of the main goals of the project is to create standardized procedures for prosecutors, defense attorneys and other participants to follow in RJ practices. Myriad questions need clear answers.

Which types of cases are most appropriate to refer to RJ? What rules should govern the defendant’s statement of responsibility? What happens when defendants admit fault but don’t complete the remedies laid out in their agreement with the victims? What confidentiality rules should apply to discussions with each party?

Also, the education component of the project will be “critical” to the project’s success, Porter-Merrill said, as the general public has relatively little understanding as to what restorative justice is or how it works. “It’s surprising how few people have actually heard about restorative justice.”

She said that what defense attorneys need to know, among other things, is how to ensure their clients’ due process rights remain intact as they undergo restorative procedures and dialogues.

Besides overcoming a lack of awareness of RJ in the state, the offices will need to address people’s preconceived notions, and perhaps resistance to it.

“I think it’s going to be important to demonstrate how this is going to be helpful to victims of crime,” McCann said. Some prosecutors and victims’ advocates might balk at restorative practices as “touchy-feely” and less effective in seeking justice for victims and preventing further crime.

“Many people see it as a soft approach and kind of a slap on the wrist, so to speak,” Westover said. But RJ procedures aren’t “a bunch of people sitting around and singing kumbaya,” she added. When a juvenile smashes a person’s window with a rock, and then has to face the homeowners and listen to their grievance, “that’s much more difficult in a lot of ways than going before a judge,” she said. But at least in that instance there’s greater chance the juvenile will understand the harm caused and be contrite, she added.

The RJ expansion agreement allots each office $50,000 to fund the research and outreach effort for a year, with the option to renew annually. Westover is confident that when the council and the offices go over the results at the end of this term, they will opt to keep the program going. But it’s hard to predict just how much RJ practices might grow with this push; developing a road map for RJ practices has no road map.

“Nobody has ever done this before,” Westover said. “It’s a big experiment.”

— Doug Chartier