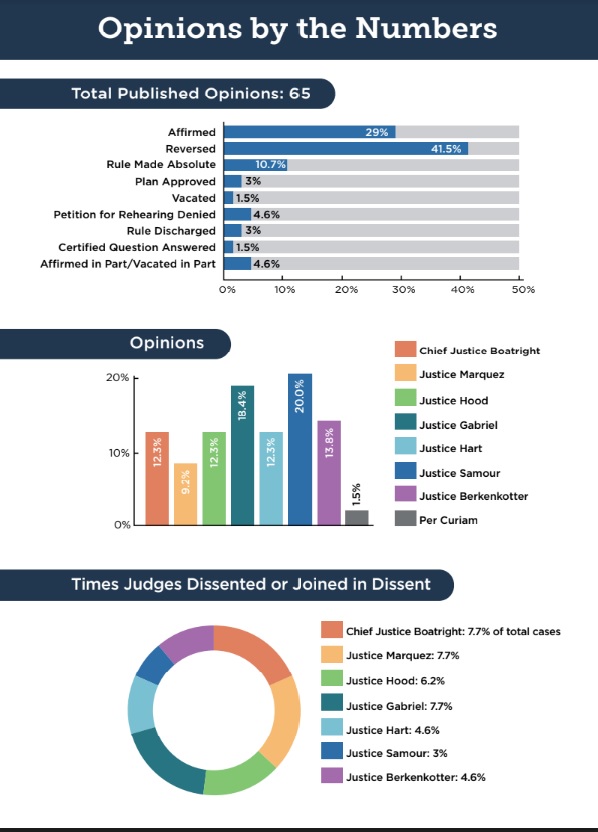

It’s been an interesting fall and spring term for the Colorado Supreme Court. The highest state court has issued dozens of published opinions from September 2021 to June 2022.

Law Week’s research indicates nearly 42% of the cases were reversed while 29% were affirmed and almost 11% made the rule absolute. Justice Carlos Samour led in writing opinions and provided 20%, while Justice Richard Gabriel was second with 18%. As for dissents, Chief Justice Brian Boatright, Justice Monica Marquez and Justice Gabriel were all tied at 7.7%.

Law Week Colorado caught up with a few Denver attorneys who shared their thoughts on what some of the biggest opinions were from September through June.

Ben Cohen, of counsel at Polsinelli, who specializes in litigation and appellate practice, said he believes the Colorado Supreme Court had a routine year compared with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Cohen went on to list many cases that stood out to him during the state Supreme Court’s session. One he saw as critically important dealt with redistricting in Colorado in November.

“In Colorado, this was the first time that the Colorado Supreme Court has reviewed a decision of a new redistricting panel,” Cohen said. “What’s great about it is this is the first year it was done. … They had challenges due to COVID, they had challenges due to the late census results, but they got it done. … [The Supreme Court] reviewed it, they described the entire process, went through it in great detail and approved the whole thing. What’s really remarkable about it is how smoothly it all went.”

In March, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that a lawsuit could continue against El Paso County Sheriff Bill Elder. The court ruled the sheriff’s office doesn’t have sovereign immunity in a case involving alleged false imprisonment after an inmate was held for months after bond was posted. The jail had put an ICE hold on inmate Saul Cisneros after the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement suspected he could be subject to deportation.

One of the major considerations of the case is whether an exception to governmental immunity that allows pretrial inmates to sue the operators of jails for injuries because of negligence, only applies to cases of negligence. The Supreme Court ruled it does not and immunity could be waived if injury was intentional.

“It’s good to know the Supreme Court is on the lookout for such cases because they took [it] … and they reversed precisely because it would lead to an absurd result,” Cohen said.

In this case, Justice Gabriel wrote a blistering opinion which said in part: “In reaching this determination, we conclude that the statutory language waiving immunity for ‘claimants who are incarcerated but not yet convicted’ and who ‘can show injury due to negligence’ sets a floor, not a ceiling. To hold otherwise would mean that a pre-conviction claimant could recover for injuries resulting from the negligent operation of a jail but not for injuries resulting from the intentionally tortious operation of the same jail, an absurd result that we cannot countenance.”

Another major case that Cohen pointed out was French v. Centura Health Corp. from May. This case involved Colorado resident Lisa French who was told her surgery would cost about $1,300 after insurance covered most of it. She later got a bill for more than $300,000 with insurance picking up about $73,000, leaving French to pay the rest. Centura then sued to collect the bill saying she signed an agreement to pay the hospital’s chargemaster rates, which are like sticker prices where the hospital doesn’t mention discounts they negotiated with insurance providers. Chargemaster was not mentioned in the contract French signed originally.

Eventually the Colorado Supreme Court reversed the Colorado Court of Appeals decision leading to French not having to pay the massive bill. A jury previously found she owed about $800.

“Basically ruling, look the hospital didn’t incorporate these chargemaster rates; basic contract law is what they applied,” Cohen said. “When the patient goes in and signed paperwork saying I’ll pay all charges of the hospital, that can’t include secret rates that were not at least even referenced because they’re secret.”

Jason Wesoky, treasurer for the Colorado Trial Lawyers Association, who has been practicing law for 21 years, shared mixed feelings about some of the rulings from the Colorado Supreme Court, arguing it doesn’t place as much value on human life as it should.

One case Wesoky brought forward as having a major impact was Rudnicki v. Bianco, in which the CTLA filed as amicus curiae. In that December case, the Supreme Court ruled that a minor has the right to recover childhood medical costs from a lawsuit, which overturned an old common law rule that said only the parents could sue for the costs associated with the child’s treatment.

Alex Rudnicki had a serious brain injury during birth and had about $400,000 in expenses during that time period. He has since needed physical, speech and occupational therapy and he will likely never live on his own. When Rudnicki was nine, his parents sued Dr. Peter Bianco, the doctor who delivered him. The child was awarded $4 million, but that award was later reduced by nearly $400,000 for his medical bills due to common law, which meant his parents are the only ones who owned the claims for medical expenses.

The parents missed their chance to recover medical costs because they didn’t realize how serious the boy’s injury was. Once they realized it, the statute of limitations had expired to sue the medical provider. Minors can bring malpractice claims up to two years once they reach the age of majority. Rudnicki claimed once the trial court award was reduced, he was left having to pay for the medical costs he got as a child.

“We used to look at children when [we] were less, I guess, civilized than we are now … as property, just like … how [society] used to look at women and that’s how we used to look at Black people in this country — they were property,” Wesoky said. “So this line of law, this thread of law goes back hundreds, if not thousands of years. The only reason why that kid couldn’t bring a lawsuit when he turned 18 and collect the value of his medical bills is because somewhere a long, long time ago, somebody decided children were nothing more than useful property. Fortunately the Colorado Supreme Court listened in that case and understood … that’s an archaic way of thinking.”

Another case that stood out to Wesoky was the Ford Motor Company v. Walker case from June, in which the CTLA was also amicus curiae. In that case, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that parties which appeal a judgment against them, no matter what the appeal outcome is, trigger an accrual of the market interest rate on the judgment, rather than the higher 9% interest rate the Colorado General Assembly came up with, which would apply before the appeal.

The case focused on Forrest Walker, who was in a car accident in 2009, when he was rear-ended in his SUV. He eventually sued Ford in 2013 claiming the car seat was defective and led to his permanent injuries. A jury awarded him $2.9 million, and Ford appealed after taking issues with the jury instructions. The Colorado Supreme Court agreed and another trial was held in 2019 and the jury awarded nearly identical damages for Walker.

Walker wanted to apply that 9% for the 10-year period from the injury date in 2009 through the case’s second trial in 2019. Ford wanted to apply the 9% only for about four years from the injury date, and then after that, begin market-rate interest through 2019, as it argued the market rate conditions should be applied during the time period during the appeal process.

“[It] devalues people’s time, it devalues their human worth,” Wesoky said. “This guy had to spend years and years and years of his life litigating only to be told by the Supreme Court after all that was said and done, his time and his life really isn’t worth nearly as much and all he was asking for was a 9% interest rate on the money he eventually recovered.”

Another case Wesoky found interesting was Skillett v. Allstate Fire & Cas. Ins. Co. from March. In that case, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled a plaintiff cannot sue an individual insurance claims adjuster under Colorado’s bad faith insurance statutes.

Alexis Skillett filed a claim with her insurance provider Allstate, for underinsured motorist benefits after a car accident in 2020. The claims adjuster denied it, so Skillett sued Allstate for breach of contract and bad faith, and also sued the insurance adjuster for statutory bad faith. The Supreme Court ruled plaintiffs can only sue the insurance provider.

“The state Supreme Court said no, apparently insurance employees get special treatment,” Wesoky said. “The state Supreme Court said even though the person who is bringing the claim, their life has been significantly impacted, the value of their life has been impacted, and the insurance company has failed or refused to recognize that, the insurance company is more interested in protecting its own employees and that law now is solidified in Colorado.”

The above cases mentioned make up six of the more than 60 cases opinions that were published between September 2021 and June 2022. Check here for a complete list of opinions that were published.