The Colorado Supreme Court looked back nearly 400 years and across the pond to a pair of property law cases from 17th century England in deciding whether to overturn one of its own precedents from 1966.

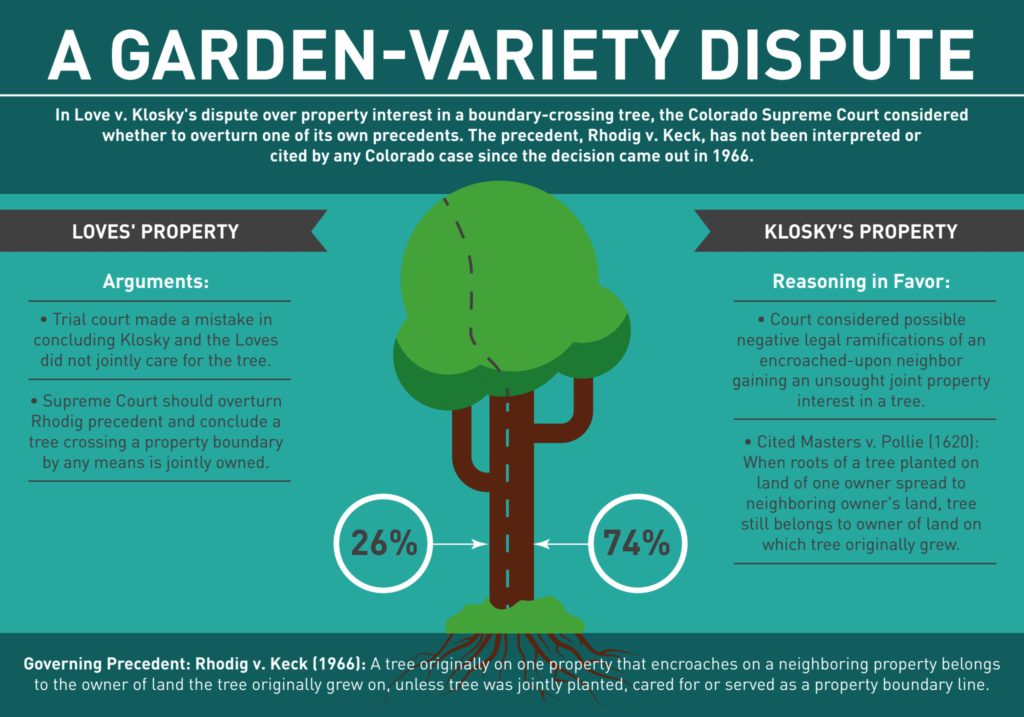

The court ultimately did not find a reason to reverse precedent in a lawsuit over a tree crossing the boundary line between two properties. In Love v. Klosky, the court ruled a tree planted on one property that grows to encroach on a neighboring property belongs to the owner of the property where the tree grew. The decision followed a ruling from 1966, Rhodig v. Keck, which no subsequent Colorado case has interpreted or cited until now.

Under the Rhodig precedent, a tree spanning two properties is jointly owned only when it is is jointly planted, cared for or serves as a property divider. The case did not apply the rule to trees serving as true property boundary lines where it’s not possible to tell whose property they grew on.

In Love v. Klosky, Keith and Shannon Love filed suit to prevent Mark Klosky and Carole Bishop from cutting down a 70-foot tree growing mostly on the Klosky property. The trial court found the tree was first planted on the Klosky property, though it existed on the land before they purchased it. The court also found the Loves had not met their burden of proof for joint ownership interest in the tree and dismissed the Loves’ claims.

On appeal, the Loves argued the court should overturn the Rhodig precedent and that the trial court erred in finding the Loves had not proven a joint ownership interest in the tree. In 2016, the Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court, but, feeling bound by the Rhodig precedent, urged the Supreme Court to review the case.

Rhodig’s status as a minority rule also drove the Court of Appeals’ request that the Supreme Court review Love v. Klosky. Five other states including Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Texas and Utah use a similar rule concerning boundary trees, while 21 states consider plants that cross property boundaries as shared property.

But the Supreme Court found Love v. Klosky’s conditions did not meet any important considerations for overturning a precedent: That more good than harm should come from doing so, that the rule was originally wrong or that changing conditions make the rule no longer sound. The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts’ findings.

“Because the Rhodig approach does not automatically transfer a property interest in encroachment-tree cases, we conclude that it remains sound,” reads the opinion authored by Justice William Hood. “And, we see no conditions that have changed to make the above reasoning any less compelling today than when we decided Rhodig.”

Rick Gleason, an attorney at the Overton Law Firm who argued the case in front of the Supreme Court on behalf of Klosky and Bishop, said he believes the Supreme Court did a good job of making a clear distinction between the circumstances in which a tree is a boundary tree and when it is not. Although the Rhodig case applied its ruling only to encroaching trees, it did not as clearly define the difference.

But Gleason did admit his surprise that the Supreme Court took an interest in the case.

He said he believes the Love v. Klosky decision will only apply to encroaching trees that clearly first grew on one side of a property line, and trees in circumstances that are not clear will be treated as boundary trees.

“I was a little surprised when the Supreme Court took it up but heartened by the fact that it was a unanimous decision, obviously,” he said.

Bennett Cohen and William Meyer, attorneys with Polsinelli who represented the Loves, did not provide comment for the story.

Two cases from 17th-century England took contrasting approaches to trees that straddled property boundary lines and have informed American cases such as Rhodig and Love. Masters v. Pollie in 1620 ruled that when roots of a tree planted on one property spread to encroach on another, the tree still belonged to the owner of the land on which it originally grew.

In 1697, the court held in Waterman v. Super that a tree encroaching on across a boundary line became jointly owned between the property holders. But the court resolved the split in favor of Masters in 1827.

In its analysis of Love v. Klosky, the Supreme Court examined possible negative consequences of overturning Rhodig and implementing a rule that any tree crossing a property line automatically becomes jointly owned. It would result in joint legal liability from any injuries resulting from the tree, for example, even if the tree encroaches mere inches across a property line.

As another example, if an encroaching tree were considered jointly owned, and were to interfere with the encroached property’s sewage line, that property’s owner could not bring a nuisance claim because the property can’t invade itself.

“We know of no other context in which a transfer of real property occurs with no action on behalf of either party and with no intent to transfer the property interest,” Hood wrote in the opinion. “We are loath to create a rule allowing for the automatic transfer of a property interest because an encroaching tree touches a property line.”

Hood couldn’t resist including some subtle humor in the opinion, referring to Love v. Klosky as a “garden-variety dispute.” Gleason laughed at the characterization, saying when he saw the joke he knew it would be “one of those” opinions.

—Julia Cardi