The Colorado Supreme Court on Nov. 1 approved a congressional map chosen by the Colorado Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission, despite objections from groups who say the redistricting plan dilutes the influence of Latino voters and other minorities.

The court noted in Monday’s opinion that its role in the redistricting process is a narrow one. In the unanimous opinion, Justice Monica Márquez wrote that the “ultimate question for this court is not whether the Commission adopted a perfect redistricting plan, or even the ‘best’ plan among the options presented to it.” The court’s job, Márquez continued, was to decide whether the final plan “fell within the range of reasonable options” while complying with constitutional requirements.

The Colorado Constitution requires the commission to create districts of equal population, comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, preserve whole communities of interest and political subdivisions, create districts that are as compact as possible and maximize the number of politically competitive districts — in that order.

Additionally, the state constitution prohibits approval of plans that protect an incumbent, candidate or party. It also bans maps that deny or abridge the right of any citizen to vote due to race or membership in a language minority, including by “diluting the impact” of a group’s “electoral influence.”

Several groups, including the League of United Latin American Citizens and Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization, objected to the commission’s map for exactly that reason.

“CLLARO is disappointed with the map. Our expert data proves that this map will dilute minority votes in Congressional Districts 3 and 8,” CLLARO said in a statement to Law Week. “It is disheartening that it was approved despite that information. CLLARO welcomes the Court’s invitation to future redistricting commissions to consider race and minority voter electoral influence and to supplement the Voting Rights Act with additional voting protections.”

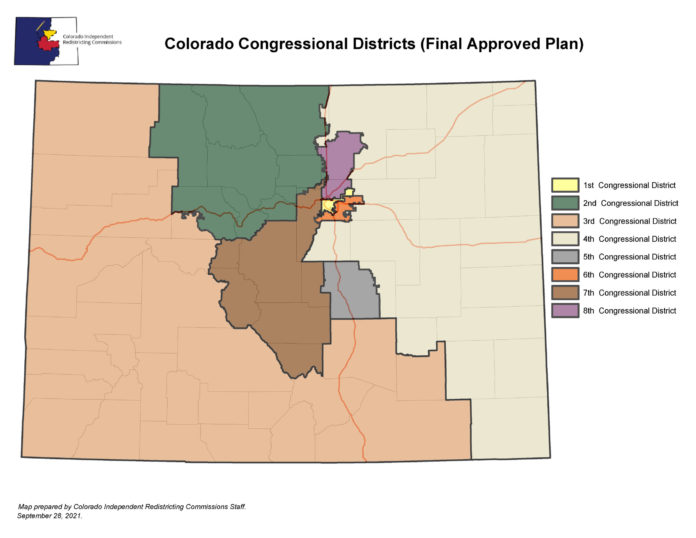

LULAC and CLLARO argued that the plan waters down the influence of Latino voters, particularly those in southern Colorado and the Denver suburbs, by combining them with white voting blocs that tend to vote against candidates Latinos prefer. Other organizations, including All on the Line, Common Cause and Fair Lines Colorado, raised similar concerns about minority voter influence in briefs and oral arguments last month.

The commission and its critics disagreed about how far it should go to protect minority voters’ influence. Opponents, including CLLARO and LULAC, argued the state constitution creates additional protections beyond those in the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits voting practices that result in denial or abridgment of the right to vote due to race or color.

However, unlike the Colorado Constitution, the VRA doesn’t use the terms “dilution” or “electoral influence.” Several of the plan’s opponents took this to mean the constitution imposes additional protections for minority voters and the redistricting commission failed to comply with these extra requirements. Some of the groups argued the commission should have created crossover districts by grouping Latino voters with white voters who support Latinos’ preferred candidates.

The commission, on the other hand, argued that the disputed language simply codifies the VRA’s existing protections into the state constitution, preserving those protections in Colorado in case future changes to federal law weaken them.

The justices sided with the commission, noting that Amendment Y, which voters passed in 2018 to create the independent redistricting process, doesn’t define “dilution” of “electoral influence,” which is “curious if this language was intended to establish new protections beyond those existing in federal law.”

The Supreme Court concluded that the commission wasn’t required to “engage in maximally race-influenced redistricting” or create “supplemental voting protections,” and its decision not to use “race-focused redistricting boundaries” wasn’t an abuse of discretion. However, the court said its decision shouldn’t be interpreted to mean the commission can’t consider race or minority voter influence when drawing district lines in the future.

“I think the most notable takeaway from the decision is that the court very clearly said that future redistricting commissions can consider minority influence districts as they set districts,” said Recht Kornfeld shareholder Mark Grueskin, who represented Fair Lines Colorado, a Democrat-backed organization that opposed the plan. “And that is an opening that is significant.”

During oral arguments, the commission warned that focusing on race at the expense of traditional redistricting criteria could “put the state on a direct collision course with the Equal Protection Clause,” leading to a federal lawsuit. “The [Colorado] Supreme Court politely but clearly said that was not a concern that any redistricting commission in the future had to have,” Grueskin said.

The court also rejected challenges over the commission’s procedures and processes. LULAC raised concerns that the commission’s discussions about minority voter influence didn’t comply with transparency or public access requirements. But the court concluded the commission’s processes, which included “numerous public hearings” and “thousands of public comments,” complied with constitutional requirements.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee argued that the redistricting process was “procedurally irregular” and “infused with last-minute confusion.” The court disagreed, noting that while the commission’s schedule was compressed and its processes changed several times, this was necessary due to pandemic-related delays in census data.

The COVID-related schedule changes made “judicial review uniquely challenging this year,” according to a news release from Wheeler Trigg O’Donnell, which represented the redistricting commission. “It was fast and furious,” said WTO partner Fred Yarger, who defended the map during oral arguments on Oct. 12. According to the news release, the WTO team only had seven days to prepare a brief defending the map and then three days to respond to 13 different briefs filed by outside opponents and supporters of the map.

“I was grateful for our legal team and for the Commission’s non-partisan staff, who have decades of experience navigating the redistricting process,” Yarger said in the press release. “It was a true team effort.”