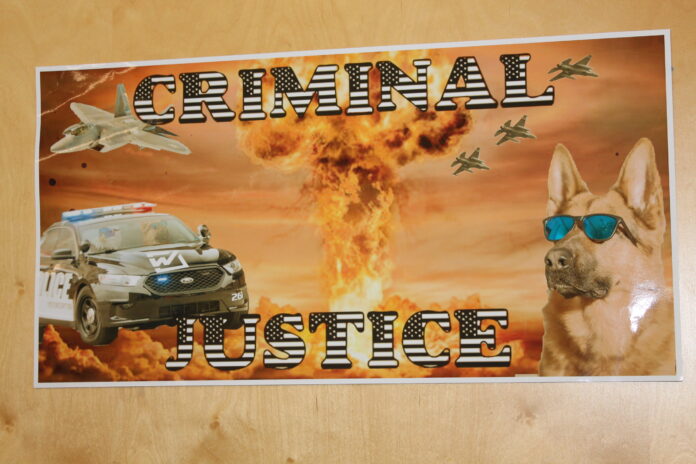

Valarie Purl’s door at Warren Tech North has an eagle and a German shepherd in a police car wearing aviators with an explosion in the background. Purl is an attorney and an instructor for the technical school’s criminal justice program.

The program is fairly sophisticated, accepting only around 50 students each year, and it almost always has a waitlist. Students who apply to be in the course are usually interested in behavioral science, law enforcement, legal practice or some combination of similar legal professions.

“I don’t think kids realize how many rights [exist] that they don’t know about,” Purl told Law Week at her classroom in Arvada, Colorado. The issue underpins a larger problem with civic literacy and legal literacy among the general public.

The class is broad. Purl explained that students start with the Constitution and go through the entire legal system through corrections. Students apply for a year with the course, and it’s open to students in junior or senior high school levels. In addition to earning their high school English credit, students have the opportunity to earn up to 18 college credits through Red Rocks Community College while they’re enrolled, putting them well on the way toward earning an associate’s degree shortly after graduating high school.

Students spend a lot of time in the classroom each week with Purl and her lightly bloodstained lab dummy named Bruce. Half of their school day is spent with their home school, which is sometimes the neighboring Arvada West but may be further away in Jefferson, Clear Creek, Gilpin or Platte counties. The other half of the day is spent with the criminal justice program at Warren Tech.

In the American Bar Association’s 2024 Survey of Civic Literacy, more than 6 in 10 respondents said the general public isn’t informed about how democracy works. At the same time, more than a third believed the public is primarily responsible for safeguarding democracy, according to the key highlights of the ABA’s report.

Perhaps more concerningly in the ABA’s civic literacy report, more than a third of respondents incorrectly thought the judicial branch enforces laws instead of reviewing laws.

But Purl thinks programs like the one she instructs can help with the larger civic literacy problem.

She estimates around a quarter of the students who go all the way through her program may go on to related legal fields as adults. At the very least, Purl said it’s likely kids who go through her criminal justice program know more about the Constitution and civil rights than kids who take standard government or history classes in high schools.

“You would think that kids would be more well-versed — or you would hope — through your political or your civics [classes] or something like that, the kids would have more understanding and knowledge of the Constitution, but they really don’t,” Purl explained.

Purl said it’s not as difficult as you may think to teach high school kids about the complexities of America’s criminal justice system.

“The biggest, I think, hurdle for them is the bubble that they live in that they don’t know what they don’t know,” she said. “They just assume that this is how it’s like in the real world. And they don’t see how sometimes it’s jaded — sometimes it doesn’t work out for the good guy.”

“Kids have a tenacious curiosity — to want to know things,” Purl explained. “So as far as the challenge of it, I don’t know if it’s a challenge so much because they yearn for that learning, and so they already have that interest.”

In Purl’s class, students participate in mock trials, interrogations, arrests, searches and a myriad of other simulations, including a police simulator one time. Purl said she thought the simulator helped the students understand some of the quick decisions law enforcement need to make in intense situations.

Purl noted the program also includes resources and support from local law enforcement and the legal community to aid and provide speakers.

The classroom and lab experiences culminate in not only a better understanding of the legal system and civics, but also how sometimes seemingly impossible decisions are made from law enforcement responses to how presidents select U.S. Supreme Court justices.

When asked about the timing of the class she teaches, Purl said that developmentally, it’s the perfect time for students to learn about these systems and how they work in the real world and not just how they’re presented in TV shows.

“I think college is a great time to do it, but I don’t think you’re going to get most of the population in college,” Purl noted. “If you’re going to get them, you’re going to get them in high school.”