Last year’s Equifax data breach exposed information on 145.5 million people. Equifax waited about 40 days to disclose the breach. They lost their consumers’ trust, costing them business while opening them up to civil lawsuits. Prior to the breach, at least 44 states had laws protecting consumer data. Alabama, Florida, Iowa, Maryland and South Dakota all passed their laws in 2018. The 40-day period Equifax waited falls within the period of disclosure for many states, consumers felt they should have found out sooner.

While all 50 states have now passed statutes on how companies are to respond to breaches, no federal law governs businesses in all sectors when it comes to general consumer information security.

Colorado’s data privacy bill is still waiting to be signed by Gov. John Hickenlooper and will be the strictest law in the nation regarding how businesses and the state government — collectively referred to as “entities” in the bill — prepare for and handle security breaches.

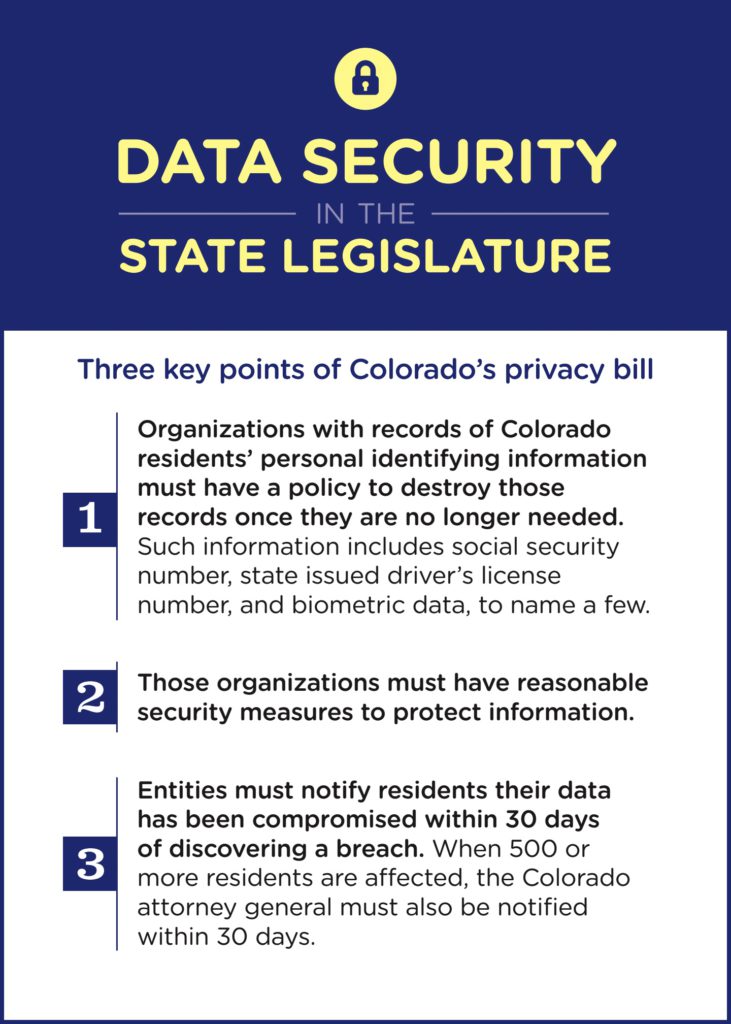

The bill has three main parts, requiring that entities have reasonable securities measures to protect personal identifying information, policies in place for destroying unneeded information and requiring them to notifiy affected residents — and in large breaches also the state — within 30 days.

Colorado’s bill sets itself apart from other states by including government organizations with businesses, bill sponsor Rep. Cole Wist said. “We shouldn’t be passing laws imposing these types of obligations on the private sector if government isn’t willing to do it itself,” he said. “There are all kinds of information that’s in government databases that’s every bit as compromising if it’s out there.”

Colorado also sets itself apart with the most wide-reaching list of what counts as personal identifying information. According to the bill, this could be Social Security numbers, a password or pass code, government issued driver’s licenses or ID card numbers, passport numbers and even biometric data, to only name a few. Biometric data is defined as data derived from measures or analysis of human body characteristics meant to authenticate the user. Although not explicitly stated in the bill, this could include fingerprints and face recognition.

Colorado also will have the shortest notification window between when a breach is noticed and when it must be disclosed to those affected. Most states give 45 days; Florida gives 30 days with the possibility of a 15-day extension. This means that Colorado residents will be among the first notified of data breaches that compromise user information. The speed at which the bill wants businesses and the government to move is intentional. Although Colorado has the tightest requirement, Wist said most people he talks to about the bill feel 30 days is too long to wait before informing victims their information has been involved in a security breach. “While the bill was pending in the legislature this session, Mark Zuckerberg testified in front of Congress that he thought that a notification period of 72 hours was something that we should be looking at,” Wist said.

Wist was willing to hold back on the notification period in order to minimize the burden of regulations and associated costs on businesses. The initial bill gave entities seven days from the date of the breach, not the discovery of the breach, to notify the Attorney General’s Office because the drafters felt that time was of the essence in determining why the breach happened and who committed the crime.

“Something needs to be done,” said Dan Nelson, a partner at Armstrong Teasdale and co-chair of the firm’s privacy and data security group. “I think there’s a lot to like in this bill in terms of attempting to move security efforts forward.” He does have one slight reservation on the bill, which falls under how the phrase “security breach” is defined and how ransomware could fall within that definition. Ransomware is where a hacker encrypts data so that it cannot be accessed and demands a ransom for the information to be accessible again.

The bill describes a security breach as, “the unauthorized acquisition of unencrypted computerized data that compromises the security, confidentiality, or integrity of personal information …” but Nelson points out ransomware only encrypts data so that the user cannot access it — it “acquire” information. However, Nelson said, if the emphasis is on the integrity of personal information being compromised, then that could include ransomware.

How businesses make personal identifying information secure has been left intentionally vague in the bill. This is for the best, said Ballard Spahr partner David Stauss, who helped draft the bill. “The law can’t necessarily envision all of these types of ways in which the information’s going to be used,” Stauss said.

“Security is sort of a moving target,” Nelson said. “What made a good security program five years ago is not necessarily what makes a good security program today.”

According to Stauss, Massachusetts is the only state to put specific regulations on how a company protects user information. He warns against this because it is only a matter of time before a company follows those regulations, yet does not do all it can to ensure that the personal identifying information in their possession is protected.

Some states’ laws give an exception to businesses whose data was encrypted when they were breached. That is not the case in the Colorado bill. Nelson explained why that exception should not be given, “If the attackers were able to acquire keys that will unlock the data, the encryption shouldn’t be an exception to your reporting obligations.”

There are a few specific regulations regarding how companies investigate their breaches. This bill applies to any company that has identifying information on any Colorado resident. When a company is breached, it must investigate if personal information has been misused or will be misused.

But not all laws are successfully enforced. Stauss said he doesn’t think this bill will not be on that list. “This statute was enacted to be enforced,” he said. Companies that violate this statute by not destroying data, not having proper security practices in place or by failing to notify Colorado residents within 30 days will face civil penalties or an injunctive relief that could be anything that satisfies the court that a transgression won’t happen again.

Stauss recommends that businesses should draft incident response plans as soon as possible, setting up the infrastructure for knowing when the business is breached and how to investigate it.

— Connor Craven