Editor’s Note: This is the third and final article profiling CTLA Case of the Year Award nominees. The winner will be announced at the CTLA dinner on May 10 and covered in the May 14 issue of Law Week.

In a case such as Shiva Rai v. St. Vrain Valley School District, which involved repeated abuse by a bus aide of a student with autism, attorneys could easily go after the low-hanging fruit — in this case, the aide’s behavior and the failure of the bus’s driver to report the abuse.

One of Denver’s most prominent civil rights law firms is again in the running for Case of the Year from the Colorado Trial Lawyers Association, and they chose not to take the low-hanging fruit.

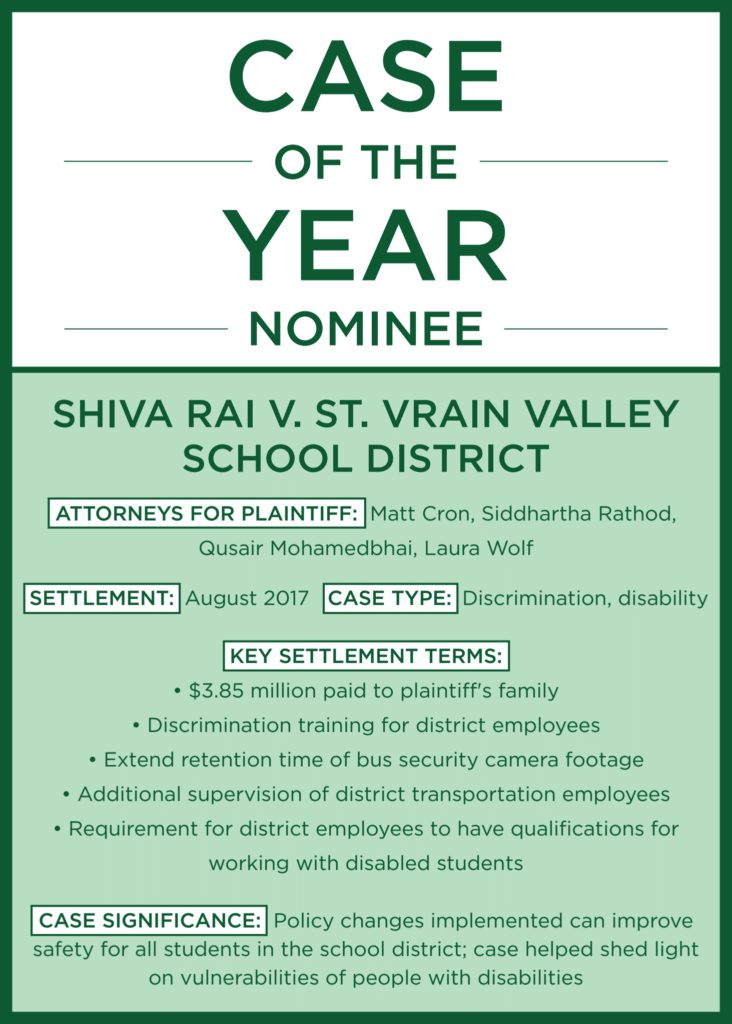

They instead focused on systemic problems in the school district that allowed the abuse to occur. Attorneys from Rathod Mohamedbhai, who received the award last year, have been nominated again, this time for a settlement with the St. Vrain Valley School District.

Last summer, the firm’s attorneys reached a $3.85 million settlement between student Shiva Rai’s family and the St. Vrain Valley School District. The district also established discrimination training for its employees and agreed to establish qualifications for employees working with students with disabilities.

An investigation revealed former aide Monica Burke would kick and hit Rai, as well as berate him about his body odor and spray him in the face with Lysol when he rode the bus to a Denver school for students with autism.

“We want to explore why people like this are able to get away with this level of abuse,” said Rathod Mohamedbhai partner Matt Cron. “So to do that, we have to explore why the governmental entity can be held responsible.”

Bus security camera footage captured several days of abuse by Burke, which the school district reviewed after a teacher saw Burke berating Rai. As part of the settlement, the district also agreed to retain camera footage for longer than the several days they previously had done.

In addition to the civil agreement, Burke received a 20-month jail sentence. Later in 2017, bus driver William Hall was sentenced to 60 days in jail for failing to report aspects of Burke’s abuse.

Cron said it would have been easy to focus their case on the aide and bus driver’s wrongdoings. But the attorneys’ affinity for getting at the underlying causes of problems to help prevent future similar harm is a signature stamp of the civil rights cases Rathod Mohamedbhai takes on. In the St. Vrain Valley case, they sought to hold the school district liable for Rai’s abuse under the standard established by Monell v. Department of Social Services, a 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case. The ruling held that a local government is a legal person subject to civil action for rights deprivation.

The complaint filed with the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights claimed negligence by the school district in failing to properly screen Burke and Hill. Cron said based on information found about their backgrounds, they should not have been hired for positions in which they interacted with children.

The district had also not provided adequate training to district employees on how to care for individuals with severe disabilities, and after district officials saw the videotapes showing Burke’s abuse of Rai, they did not remove Burke from her post until a few days later, which subjected Rai to further mistreatment.

“Under the municipal liability standard, you have to show that the school district itself caused the constitutional harm,” Cron said. “It’s not enough just to show that one of their employees violated a constitutional right.” Under the Monell standard, a person or entity in a supervisory role can’t be held liable for the bad conduct solely by those under them, so in Rai’s case, the attorneys needed to prove bad conduct by the school district itself.

The case’s additional implications of race discrimination under Title VI were tricky to prove, Cron said, because Burke did not make overt racial comments to Rai. But he said Rai was the only student of color on the bus, so race seemed to be a factor in why he was targeted.

The attorneys reached the case’s settlement before the litigation stage, but much of the detail about the abuse Rai faced still came to light because of the criminal charges against Burke and Hall. Cron said early settlement has the advantage of more flexible conditions such as the sweeping policy changes achieved in Rai’s case.

In litigation, by contrast, settlement terms tend to be more limited to monetary relief.

“Whereas with settlement, anything goes. It’s whatever the parties agree upon,” Cron said. “So in our view, those early settlement opportunities carry with them a greater chance of implementing these non-economic terms.”

He added he believes Rai’s family benefitted from avoiding a taxing litigation process, which would likely have involved an independent medical examination and exacerbated the family’s stress.

Cron said that to him, an important part of the case’s outcome is the agency it helped give to the tight-knit autism community, which he added rallied around in support of Rai’s family. Autism is a much more widespread issue than Cron realized, he said.

Cron said that to him, an important part of the case’s outcome is the agency it helped give to the tight-knit autism community, which he added rallied around in support of Rai’s family. Autism is a much more widespread issue than Cron realized, he said.

“There’s just not as much awareness as there should be about the challenges that students with autism face in education,” he said. “One of the sources of pride in this lawsuit is to shed light on the challenges that this community faces.”

Shiva Rai v. St. Vrain Valley School District is one of three nominations for Case of the Year, all three of which involve victories for individuals with disabilities. Attorneys Paul Maxon, Sarah Parady and Amy Trenary received a nomination for Hayes v. SkyWest Airlines, an Americans with Disabilities Act case resulting in a $2.45 million award for the plaintiff. Jack Robinson of Spies Powers & Robinson, Brian Wolfman of the Georgetown Law Center and Jeffrey Fischer of Stanford Law School are nominated for their work in Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, which resulted in an 8-0 U.S. Supreme Court decision last spring.

— Julia Cardi