A proposed amendment to the Americans with Disabilities Act intends to give businesses more leeway in fixing public accommodation violations on their premises.

A congressional bill that aims to curb so-called “drive-by lawsuits” under Title III passed the House of Representatives on Feb. 15 and is on its way to the Senate. If signed into law, potential plaintiffs would have to give businesses notices of possible Title III violations and provide them a chance to remedy them before filing a lawsuit. Regardless of whether the bill ultimately succeeds, it calls attention to a growing segment of ADA litigation that often takes businesses by surprise. Title III of the ADA carries accessibility requirements that a range of businesses must follow. Many of these include specifications such as the size and location of handicapped parking spaces and various required signage. In recent years, it has become more common for a plaintiff to file scores of lawsuits against businesses alleging Title III noncompliance, many of which get referred to as “drive-by lawsuits” based on the notion that plaintiffs might not have actually visited the businesses they’re suing.

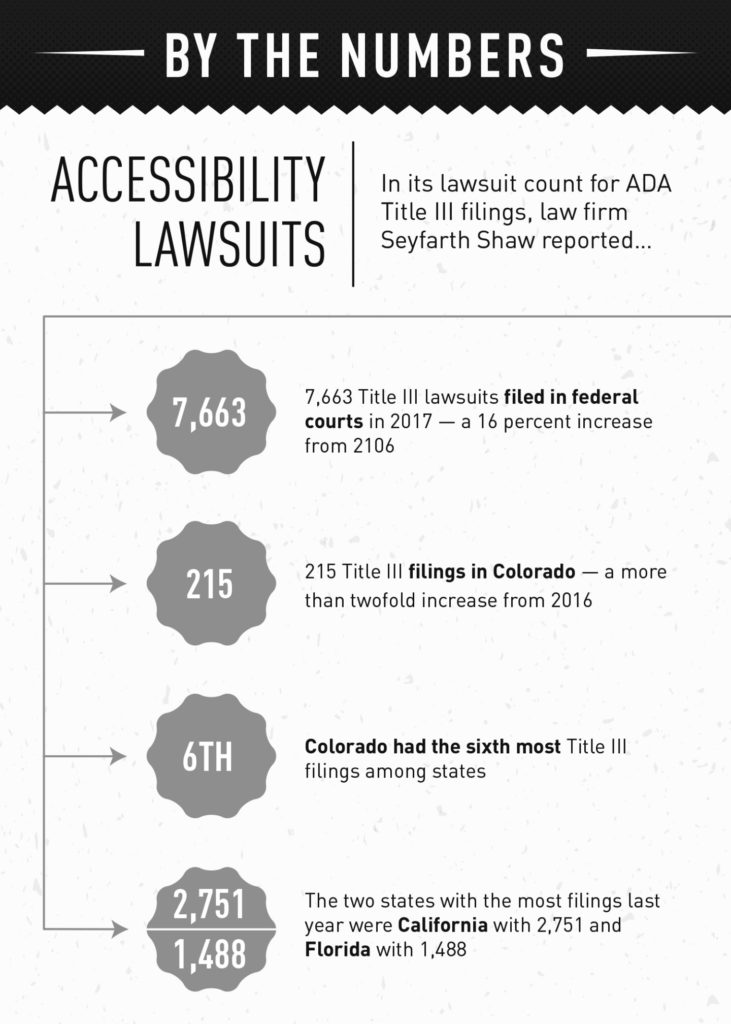

More than 7,600 Title III lawsuits were filed in federal courts across the U.S. last year, which is nearly triple what courts saw in 2013. While a far cry from the thousands of filings in California, Florida and New York last year, Colorado saw 215 Title III suits in 2017, more than double its total from 2016.

Although it’s unclear what percentage of these filings fit the description of a drive-by suit, businesses blame that subset of Title III litigation, in part, for the rising total in recent years.

“In the past few years, there’s been a rapid and drastic increase in Title III litigation,” said Amy Miletich, a shareholder at Miletich PC whose practice deals in a range of ADA-related issues. Many of the Title III lawsuits are filed by what have often been referred to as serial plaintiffs, Miletich said. The lawsuits are sometimes characterized by plaintiffs who might not have suffered a direct harm from the Title III violation; some have been known to use Google Earth satellite images to find public pools that lack a compliant pool lift and then pursue a violation based on that discovery, she added.

Republican Rep. Ted Poe of Texas introduced HR 620, or “the ADA Education and Reform Act,” which also has Democratic sponsors from California. Under the bill, anyone seeking to sue a business for failing to make a public accommodation or remove an “architectural barrier” under the ADA must first give that business written notice that points out the alleged violations. The business then has 60 days to give that person a written outline of the steps it will take to remove the barrier. Once the potential plaintiff receives the plans, he or she can then bring a civil suit if the business fails to make “substantial progress” in removing the barrier after another 120 days.

The potential plaintiff’s notice letter must also describe the circumstances in which he or she “was actually denied access to a public accommodation” and whether the barrier was permanent or moveable. That added detail appears to filter out complaints by litigants who never visited the allegedly noncompliant businesss.

The bill drew condemnation from organizations that advocate for people with disabilities. Kevin Williams, legal program director for the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, called HR 620 “a travesty [that] upends the intent and purpose of the ADA.”

“No other individuals protected by our civil rights laws are treated this way, and individuals with disabilities should not have to bear the burden of asking a business not to discriminate against them before the business comes into compliance,” Williams said in a statement.

Businesses by-and-large intend to comply with the ADA’s public accommodations requirements, and they typically make the correction regardless of how they respond to the complaint, said Megan Holstein, a principal at Jackson Lewis in Denver. The firm’s Denver office is representing defendants in active Title III cases and has litigated several others in the past, she added.

“The problem is once the lawsuit is filed, not only is the business going to fix the issue… they’re stuck with defending the lawsuit,” Holstein said. She added that HR 620 appears to be a “good solution” for limiting drive-by lawsuits as people with disabilities would still be provided access to the accommodation, and businesses would be given a “cure period” to remove the barrier once it’s brought to their attention.

For now, most drive-by lawsuits that businesses see don’t carry significant damages and tend not to make it into court, as the cases tend to settle, Holstein said. She added, however, that the bigger issue for businesses is that more Title III lawsuits are gathering into class actions.

— Doug Chartier