One of the defendants embroiled in a massive au pair class action will get to arbitrate the claims against it, thanks to an appellate court decision last week.

On Tuesday, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the district court should allow an au pair agency to arbitrate the claims it is facing by severing an unfair provision from the rest of the arbitration agreement. While the appellate court decided the case under California law, its analysis as to what makes an arbitration agreement enforceable gives Colorado employers food for thought.

In Beltran v. InterExchange, current and former au pairs are suing multiple agencies claiming federal antitrust, racketeering and wage-and-hour law violations. In February, U.S. District Court Judge Christine Arguello granted class certification to more than 91,000 au pairs in the lawsuit, which alleges the agencies colluded to keep the au pairs’ wages low.

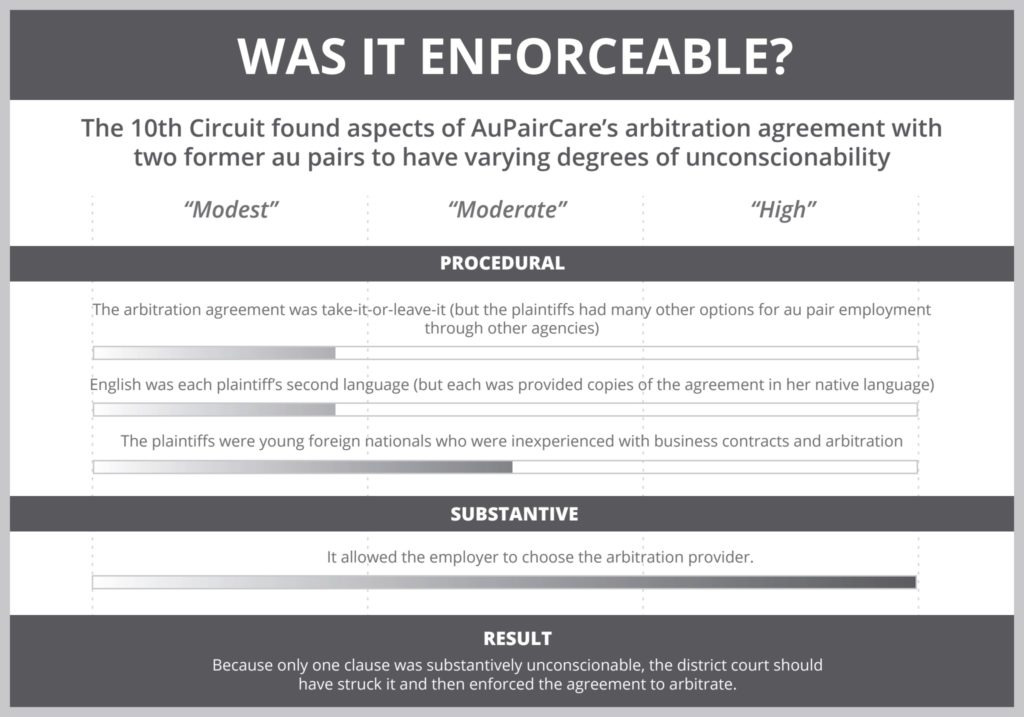

One of the au pair agencies, AuPairCare, filed a motion to compel arbitration, which the district court denied, having found the agreement unconscionable on multiple grounds. The 10th Circuit, however found only one of the clauses to be substantively unconscionable — that the APC reserved the sole right to select the arbitration provider — and reversed the district court ruling.

“Because we have found only one substantively unconscionable clause, the contract is not permeated by unconscionability,” according to the panel opinion written by Judge Carolyn McHugh. “In this case, we can easily sever the offending clause from the remainder of the agreement.”

Former au pairs Juliane Harning and Laura Mejia Jimenez signed agreements with APC to be sponsored for au pair work in the U.S. They argued that the agreements they signed shouldn’t compel them to arbitrate because they are substantively unconscionable as well as procedurally unconscionable — the circumstances surrounding the arbitration agreement made it overwhelmingly one-sided against them.

But in weighing the plaintiffs’ arguments that the agreement was procedurally unconscionable — including that they were young foreign nationals with little familiarity with arbitration — the appellate court found that aspect to only be moderately unconscionable at most. It also rejected the plaintiffs’ arguments that APC’s fee-shifting and forum selection clauses were substantively unconscionable as well.

But the 10th Circuit found that the clause allowing APC to unilaterally select the arbitration service, however, was substantively unconscionable to “a high degree.” APC argued that there was a distinction between choosing an arbitration provider, as the contract language specified, as opposed to a particular arbitrator, but the panel was unconvinced.

“Nothing would prevent APC from selecting an arbitration provider with only one arbitrator favorable to APC or from selecting an arbitration provider that employs only biased arbitrators,” according to the opinion.

For employers looking at Beltran v. InterExchange for guidance on arbitration clauses, the 10th Circuit decision carries a couple caveats, said Devin Daines, an employment attorney at Lewis Bess Williams & Weese. First, it was decided under California law because that was the state law governing APC’s contract.

Second, it was an atypical employment arrangement because, as the 10th Circuit pointed out, the plaintiffs signed on with the agency not for “necessary employment” but mainly to come work in the U.S. and improve their English skills. Job candidates in a typical setting will feel more compelled to accept a take-it-or-leave-it arbitration agreement regardless of whether it’s fair to them.

“That said, I think there are still a lot of takeaways for employers who want their arbitration agreements to be enforced and stand up in court,” Daines said.

The court stressed throughout the opinion that the plaintiffs certified they understood the contract and its terms despite their later arguments. Key to the employer’s defense was that the contract spelled out multiple employee acknowledgements. “I think those are all good acknowledgements for employers to use to ensure that procedurally their agreement isn’t unconscionable,” Daines said.

APC had also covered several bases by providing Harning and Jimenez, who are originally from Germany and Colombia, respectively, with translations of the agreement in their native languages. That undercut the plaintiffs’ argument that their status as foreign nationals made it harder to understand the contract terms and therefore made the agreement procedurally unconscionable, Daines said.

When the panel singled out the arbitrator selection provision in APC’s agreement as substantively unconscionable, it also pointed out how the agency could have made that clause enforceable. APC could have named its preferred arbitration service in the agreement, which the other party could then assess for neutrality:

When the panel singled out the arbitrator selection provision in APC’s agreement as substantively unconscionable, it also pointed out how the agency could have made that clause enforceable. APC could have named its preferred arbitration service in the agreement, which the other party could then assess for neutrality:

“Where the specific arbitration service is named in the agreement, the weaker party can assess the neutrality of that provider before executing the agreement and will not be subject to unfair surprise when the stronger party later selects a suspect arbitration service,” according to the opinion.

Besides naming their preferred provider, employers can also just be silent on the issue of arbitrator selection, Daines said. In that case, the Federal Arbitration Act or state statute on arbitration could fill in the gap on determining how the arbitrator will be selected. But he added that naming a preferred provider is often the better option for employers.

Daines noted that a court finding an arbitration agreement enforceable encompasses a multitude of factors, both procedural and substantive, so employers must consider all of those factors holistically. “There’s no magic bullet to any of this.”

— Doug Chartier