Through new federal legislation, a blocked federal rule and a decision from a tech giant, mandatory arbitration agreements had a landmark year in 2017 with a patchwork of events reshaping the playbook for the future. Considering the significant attention on sexual harassment, some experts noted the importance of distinguishing between shifting attitudes toward arbitration in the harassment context from arbitration in other types of disputes.

“The ubiquitousness of the #MeToo movement has to make every employer sit up and wonder, what do we do about sexual harassment differently now from how we’ve been dealing with it?” said John Doran, a labor and employment attorney with Sherman & Howard in Arizona. “And one of those ways is how you resolve conflicts like that, through arbitration or otherwise.” He explained he doesn’t believe the move away from arbitration in the sexual harassment context represents a shift away from it in other types of disputes, such as consumer finance matters.

“You look at a credit card provider who will have hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of users, and could have all kinds of tiny little claims against it,” Doran said. “And I think there is, at least in some views, an acknowledgement that a company [with] that many potential pieces of litigation should have the right to control its legal exposure through consumer arbitration agreements.” He added comparing consumer grievances to sexual harassment is comparing apples and oranges.

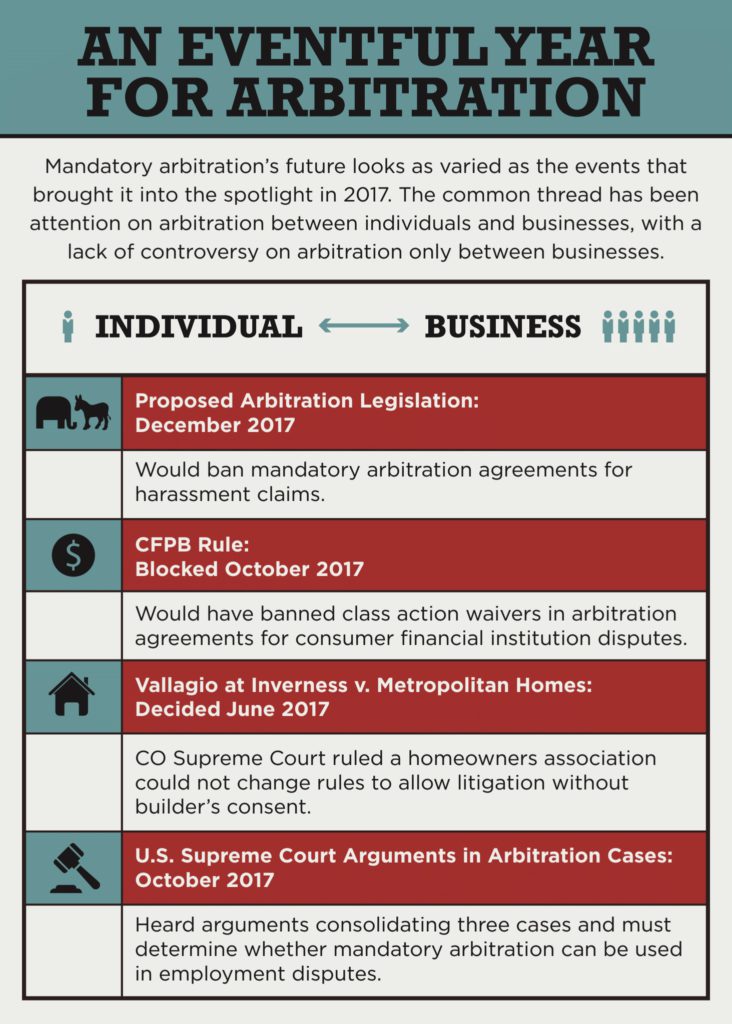

In October, the U.S. Senate voted to block a rule rolled out by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau last summer that would have banned arbitration agreements from barring class actions in consumer disputes with financial institutions. Also in October, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments consolidating three cases that will have implications for how far arbitration agreements can reach in the employment context.

And early in December, the #MeToo movement spurred new proposed bipartisan federal legislation to ban the agreements for harassment claims. Shortly after, Microsoft announced its intention to voluntarily end mandatory arbitration agreements for harassment claims.

A common thread among the events that put arbitration squarely in the news last year is that they concerned mandatory arbitration agreements between individuals and businesses, especially in the financial realm, rather than solely between businesses.

Stinson Leonard Street partner Zane Gilmer said the latter type of arbitration doesn’t often attract the attention of activists because concerns that exist for disputes between individuals and businesses, such as bargaining power disparities or sophistication levels, are not as prevalent in business-to-business disputes.

Gilmer said the line can get murky for arbitration critics when it comes to the type of dispute, and some will decry the practice regardless of whether it’s a sexual harassment complaint or a finance matter.

“There are certain anti-arbitration advocates who, for whatever reason, don’t see the differences between those types of actions,” he said. “They just see arbitration as being bad in general. … But from a practical perspective, there are real differences between these types of issues.”

He also noted the importance of the distinction between the shift away from arbitration in the sexual harassment context, pointing to Microsoft’s recent announcement.

“Microsoft is apparently not doing away with arbitration agreements for all other things,” Gilmer said. “It’s simply carving out this particular issue, and so it’s made a determination that it’s best for everyone not to use arbitration in sexual harassment issues.” He said he would put Microsoft’s decision under the umbrella of corporate social responsibility.

Arbitration and Confidentiality: A Thin Line

Doran acknowledged the #MeToo movement has directly affected legislators and company policies on arbitration. But he said he believes much of the frustration over arbitration that has arisen from the movement seems to be misplaced frustration over confidentiality, and the two have been often confused with each other.

“But they’re not one and the same, necessarily,” he said. “Yes, it’s appalling that Harvey Weinstein got away with what he did for all those years and settled all those claims that he settled confidentially. But that had absolutely nothing to do with arbitration. … One of the reasons many of these people did not come forward, like Rose McGowan, is because they were subject to confidentiality agreements, not arbitration agreements.”

Burg Simpson shareholder Michael Burg said he believes confidentiality in general “shields the wrongdoer from their action,” and that judges should make the ultimate decisions about confidentiality of settlements. Although he does not favor confidentiality, he said he has to consider his obligation to his clients.

“If my client says they want to take the settlement, I don’t have a choice [in confidentiality],” Burg said. But Doran said for now, he does not believe employers, by and large, have a pressing need to change their arbitration practices.

“If Congress disagrees, if the states in which you do business disagree, they will legislate and change the way you arbitrate,” he said. “Until then, I don’t see a reason to change how you arbitrate.”

—Julia Cardi