Following a federal appeals decision, the Federal Trade Commission’s ability to police companies over cybersecurity remains intact, except that it must be specific on what it commands those companies to do.

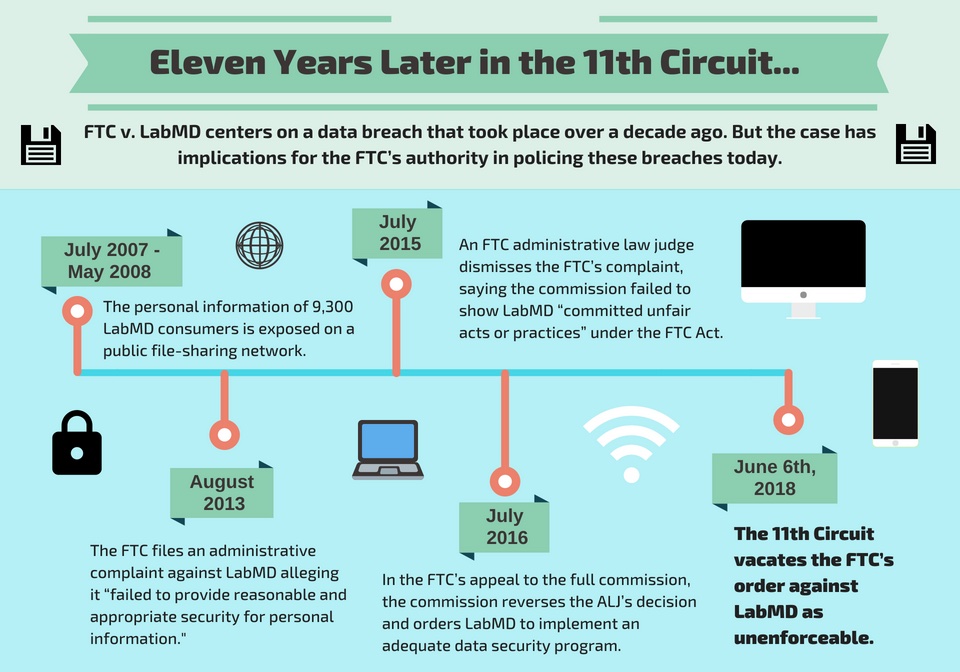

On June 6, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals vacated an order the FTC issued to a medical diagnostics lab that it implement a data security program that meets the commission’s standards. While the court didn’t discount the FTC’s authority to act against LabMD, which had experienced a data breach, it ruled the FTC’s order to be unenforceable because it didn’t direct the company to stop committing an “unfair” practice under the Federal Trade Commission Act. With a dearth of case law outlining how far federal agencies can go in enforcing cybersecurity standards, the long-awaited LabMD decision is significant even if it muddies the waters of data security regulation.

For years, the FTC has acted as the federal government’s de facto spearhead in cybersecurity enforcement. It has brought actions against companies under the theory that inadequate data protection — whether it precipitated a data breach or not — constitutes an “unfair or deceptive” practice under Section 5 of the FTC Act. The FTC’s cybersecurity authority was upheld in the 3rd Circuit in a 2015 ruling, FTC v. Wyndham Worldwide. But the 11th Circuit’s rebuke could place boundaries on what remedies the commission can demand of defendants under Section 5.

In 2005, an Atlanta-based LabMD employee had installed the file-sharing software Limewire on a company computer. Through the software, a folder with nearly 10,000 LabMD customers’ personal data was inadvertently shared on a public network. A company called Tiversa discovered the folder and offered to sell security remediation services to LabMD. When LabMD refused the offers, Tiversa alerted the FTC, which eventually brought action against the testing lab.

The FTC’s 2013 complaint claimed that LabMD violated Section 5 by engaging in “practices that … failed to provide reasonable and appropriate security for personal information on its computer networks.” It didn’t allege any violating acts the company was doing, but rather acts or measures it should have taken in order to comply with Section 5. That distinction would prove pivotal in the 11th Circuit’s ruling.

An FTC administrative law judge dismissed the FTC’s complaint in July 2015 on the grounds the commission failed to prove that LabMD committed unfair acts, and that it couldn’t prove the data breach likely caused substantial injury. The full commission would overturn the dismissal and enjoin LabMD to install a data security program that satisfied the FTC’s reasonableness standard. On appeal, the 11th Circuit found the FTC’s command to be unenforceable.

“It does not enjoin a specific act or practice. Instead, it mandates a complete overhaul of LabMD’s data-security program and says precious little about how this is to be accomplished,” according to the opinion by Judge Gerald Tjoflat.

The LabMD ruling made no mention of FTC v. Wyndham Worldwide, in which the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the FTC’s ability to prosecute certain substandard cybersecurity practices as Section 5 violations.

The LabMD decision exposed what was “an amorphous enforcement” of Section 5 as it relates to cybersecurity, said Aloke Chakravarty, who co-chairs Snell & Wilmer’s white collar defense and investigations practice group in Denver. “[The FTC] did not exercise their authority with enough specificity to justify this broad injunctive relief they asked for,” Chakravarty said.

But legal departments shouldn’t read the LabMD decision to say that the FTC lacked the jurisdiction to act against LabMD, he added. “Because the court assumed, but didn’t decide, that the FTC does have the authority here, where regulations aren’t clear, companies should assume that administrative agencies are going to exercise jurisdiction in cybersecurity,” Chakravarty said.

Chakravarty noted that the LabMD case is an outlier in which the defendant continued to fight the FTC’s Section 5 claims. The vast majority of such cases have resolved without litigation — a trend Chakravarty expects to continue for the foreseeable future.

Still, FTC v. LabMD appears to complicate the landscape of federal cybersecurity regulation.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty among [cybersecurity law] practitioners about exactly what this means,” said Austin Chambers, an associate at Lewis Bess Williams & Weese in Denver. It can be assumed that the FTC will still have the authority to enforce Section 5 violations in the cybersecurity space, but the LabMD decision might limit what remedies the commission can order a company to implement, he added.

As significant as the decision is, it may not prompt companies to adjust what they’re already doing in regard to data security and privacy for the time being, Chambers said. It won’t change the fact that they need to maintain reasonable data security standards, which isn’t just their obligation to the FTC but also state statutes and more-specific industry regulations like HIPAA. The LabMD decision is limited to what the FTC can or can’t do. “It’s more I think that it potentially reduces how effective the FTC can be as a cop on this beat,” he said.

So far it’s an open question whether the FTC will seek en banc or even U.S. Supreme Court review of the decision.

Chakravarty said that even aside from the FTC’s setback in LabMD, it is unlikely that the federal government will become more aggressive in cybersecurity enforcement for now. Reasons for that include the continued lack of a federal data breach statute and the relaxed federal regulatory environment.

But that might leave an opening for state regulators and attorneys general to get more involved, he said. “They will be playing a much larger role in enforcement of this undefined space.”

This legislative session, Colorado enacted a bill that installs some of the most robust breach notification requirements in the U.S. It also underscores how the new Colorado Attorney General — whoever that is after November’s election — “has room to be the primary watchdog in cybersecurity” in the state, Chakravarty said.

— Doug Chartier