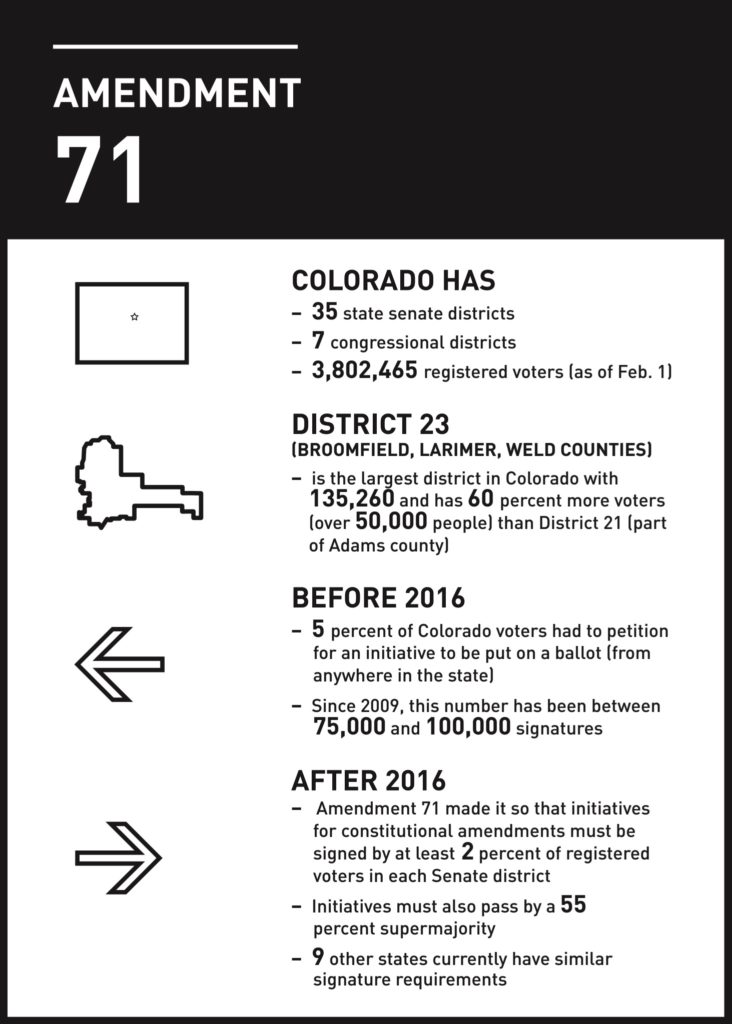

A federal district court ruling last month deemed part of Colorado’s “Raise the Bar” amendment unconstitutional. Amendment 71, which was passed by a 55 percent margin in 2016, added a supermajority vote and geographic requirements that make it more difficult to amend the state constitution.

The suit was filed in April against Colorado Secretary of State Wayne Williams. Plaintiffs argued Amendment 71 violated the First Amendment and the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which stipulates a one-person, one-vote rule. Plaintiffs include two individuals and two organizations, the Coalition for Colorado Universal Health Care and ColoradoCare Yes, that supported and tried to pass Amendment 69 in 2016. That amendment would have created a health care payment system to finance universal health care in the state. It proposed an additional 10 percent payroll tax from employers and employees to finance the program. The amendment failed by a nearly 79 percent margin.

Federal district Judge William Martinez issued the decision in response to the state’s motion to dismiss and denied it, effectively converting it to a summary judgment issue because there were no factual disputes.

Though the plaintiffs argued that repeal should mean repeal of the entire amendment because of the Colorado Constitution’s single-subject rule, the ruling kept the supermajority component intact. Martinez wrote that no case law was cited that established that the rule “has any bearing whatsoever on severability.”

The state Attorney General’s Office declined to comment on the ruling, but the state has said it plans to appeal in the event that last month’s ruling is considered the final judgment in the case. Martinez gave the state until March 9 to show cause and asked the state to provide dates and information on the 2018 ballot process that the court should be aware of going forward, should the decision disrupt ongoing petitions for elections later this year. Universal health care supporter Bill Semple is a plaintiff in the suit. Despite Amendment 69’s failure to pass, he has continued to work with the organizations to get another universal health care measure on the ballot, but he says the requirements of Amendment 71 have made it next to impossible.

“When you collect signatures to get something onto the ballot, you don’t know what district a person is from,” Semple said. “You expect about 70 percent of them to be valid, if 70 percent are valid you’re doing good.”

Semple said to satisfy Amendment 71’s requirements, after collecting signatures, canvassers would need to have a process in place to determine where each signature is from and then make sure the two percent requirement has been met.

Ralph Ogden, attorney for the plaintiffs argues that the amendment creates barriers for citizen groups that make it nearly impossible to get measures onto the ballot.

“That strikes at the heart of popular democracy,” he said. “If a majority of people want it, there’s no reason to allow a minority in one part of the state to keep it off the ballot. It’s inimical to the whole notion of democracy, that majority should rule.”

In order to get a measure on the state ballot, proponents are required to collect the number of signatures equal to 5 percent of the total number of votes cast for the Secretary of State at the previous general election. That number is 98,492 for 2018. And though statutory changes satisfy these requirements, Amendment 71 altered the process for constitutional measures.

Those must receive a supermajority vote of 55 percent and include 2 percent of registers voters’ signatures from each of the state’s 35 state senate districts.

“Only very well-funded issues that have tremendous backing behind them would be able to meet those requirements. It basically makes it impossible or extremely expensive. I don’t know how you would do it without tremendous administrative backup,” Semple said.

Amendment 71 was supported by Gov. John Hickenlooper, a handful of local government officials throughout the state as well as dozens of industry, consumer and business associations.

Raise the Bar Colorado argued that because the process for statutory and constitutional amendments was the same, constitutional additions that need clarification require an election to solve the issue.

Proponents argued it necessarily should be more difficult to amend the state’s constitution, and that these types of changes over time have made the Colorado Constitution a “special interest playground.”

As for other states with similar laws, in a footnote Martinez acknowledged that the ruling has no bearing on them but “this decision may cast doubt on them.” The note goes onto to state that though the Colorado federal district court may be the first in the country to rule this way on the ballot requirement issue, that is “no reason not to resolve the case, or defer to Colorado simply because it can point to nine sister states that potentially dilute the value of registered voters’ signatures in the same manner.”

— Kaley LaQuea