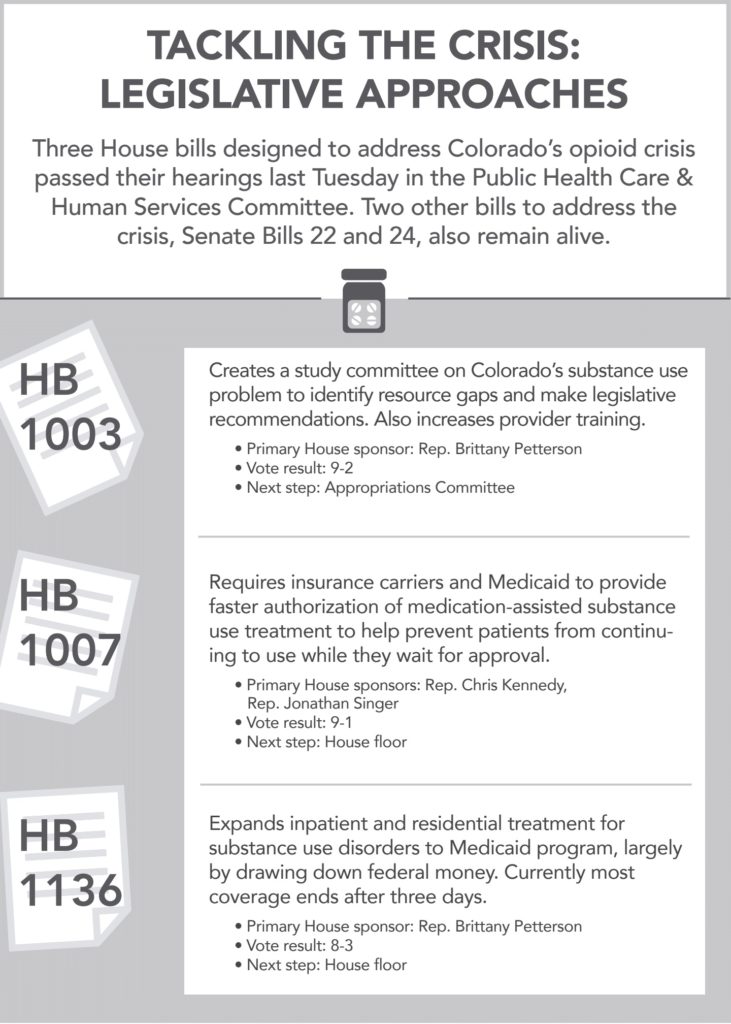

The Colorado House of Representatives’ Public Health Care and Human Services Committee gave the go-ahead Tuesday for three bills designed to address gaps in access to treatment to help solve Colorado’s opioid crisis.

The committee sent forward House Bills 1003, 1007 and 1136 with bipartisan support. HB 1136 expands inpatient and residential treatment to Medicaid programs. And according to some testimony for the bill, it might have significant policy backing from a few different health care laws.

Bethany Pray, a health care attorney at the Colorado Center on Law and Policy, testified in favor of House Bills 1007 and 1136. She spoke about both the policy and cost-saving benefits of expanding residential and inpatient treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Pray explained in her testimony that the proposal made by HB 1136 seeks a waiver of a federal Medicaid rule prohibiting funding of behavioral care provided to most patients in residential treatment centers with more than 16 beds.

The state can obtain a waiver through Section 1115 of the Social Security Act. The provision allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to approve experimental or demonstration projects that take state-specific policy approaches to helping Medicaid enrollees.

In the national context, according to Pray, there are currently 32 waivers through Section 1115 for behavioral health programs before the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS has so far approved seven waivers for expanded residential and inpatient care.

She said passing HB 1136 may actually bring Colorado’s treatment services into better compliance with another federal law, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act.

The 2008 statute disallows greater restrictions on behavioral services, under which treatment for substance use is classified, than on medical services. Consequentially, Medicaid programs and private insurance providers that provide coverage for nursing care in residential settings can’t bar coverage of residential treatment for behavioral services.

“Colorado’s Medicaid and behavioral health care system today is fragmented and discontinuous in many respects,” she said. Pray pointed to an 1115 waiver proposal from West Virginia, one of the states hit hardest by the U.S. opioid crisis.

“In seeking a continuum of care that would provide the right care in the right setting at the right time, they propose to establish appropriate standards of care, improve care coordination and care transitions to promote prevention and better integrate physical and behavioral health,” Pray said.

She continued to say that efforts already underway in Colorado to provide better substance use treatment could be better measured and organized through the 1115 waiver process proposed by HB 1136.

In addition, she said, expanded residential and inpatient treatment could result in cost savings in emergency rooms and detox facilities.

More cost savings could also come from Colorado looking to how other states have designed their waivers to see what types of care initiatives seem most effective and efficient.

“It’s my view that Colorado is violating the Parity Act now, and must remedy that by finding a way to cover residential treatment,” Pray said. “The waiver is a good way to do that.”

HB 1003 creates a study committee for the state’s substance use problem to identify resource and treatment gaps and to make legislative recommendations. HB 1007 requires Medicaid programs and private insurance providers to reduce the time window of authorization for medication-assisted substance use treatment.

The requirement aims to prevent patients from continuing to use drugs while they wait to begin treatment.

The trio of bills passed in committee is part of a larger package of proposed bipartisan legislation to tackle Colorado’s opioid problem.

“This has been a long journey to get here today, in fact, 30 years’ journey,” said Rep. Brittany Petterson, a primary sponsor of House bills 1003 and 1136. Petterson spoke about her mother’s three-decade struggle with drug addiction that began when a doctor prescribed her large amounts of opioids to curb her back problems. He eventually realized she had developed a dependency and stopped the prescriptions, but Petterson’s mother did not have access to treatment and turned to heroin.

“Our story is just like thousands of other families in Colorado and across the country from beginning to end,” Petterson said. She attributed the opioid crisis in the U.S. to policy failures and a “broken system.”

Senate Bill 40, which contained a controversial provision allowing the creation of a pilot safe injection site in the state, was postponed indefinitely by the Senate’s State, Veteran and Military Affairs Committee last month. Senate Bills 22 and 24, designed to address opioid prescription practices and expand the availability of behavioral health care providers in geographic shortage areas, remain alive. Senate Bill 22 passed to the House in February. Senate Bill 24 has yet to be heard in committee.

—Julia Cardi