Eric Voogt has worked with process servers for all of his 20 years as an attorney. And his experience with the often-frustrating status quo was enough to push him to find a better way.

Voogt, a shareholder at Glade Voogt Lord Smith, is also the creator of Proof, an app that is intended to provide transparency, efficiency and proof in process serving. The young app is already active in Colorado and will soon be growing into other markets. And Voogt, who is both a corporate attorney and now a startup owner, is seeing his career shift from law to business.

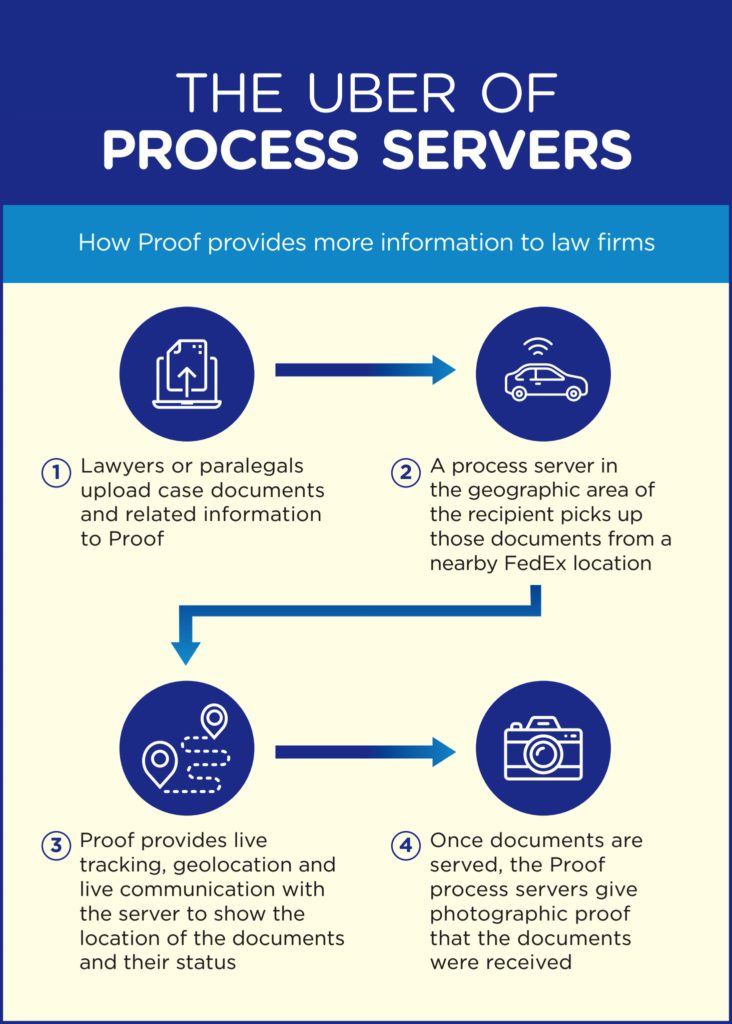

The app is a little bit Uber and a little bit Dominos Pizza Tracker. Instead of showing the ETA for a ride pickup or giving updates on when a pizza is out of the oven, Proof provides constant updates, direct interaction and a GPS tracker to show the status of documents during the process of serving them.

Each of those components dealing with communication or location responds to outdated practices in service of process. Despite being a multi-billion dollar industry — estimated at $3.5 billion a year — process serving is often a “mom-and-pop operation,” Voogt said.

Typically, a lawyer or paralegal serves documents such as subpoenas by identifying the party to serve, looking up a process server company in the their area, faxing the relevant documents and then relying on them to act as an intermediary with the actual process server who delivers the documents. The time where the process server locates the party and serves the documents can go on for days without update, and the server often gets paid the same regardless of whether they’re successful or not.

“Frustration has accelerated as technology developed, and this industry didn’t keep up,” Voogt said. “It was frustrating to our staff. We went through process server after process server, and then it hit home that the system wasn’t effective and certainly wasn’t efficient.”

The proverbial straw that broke Voogt’s back was when he received a default judgment in a case and, upon collection, the other party claimed they had never been served. The judge decided that without any way of knowing whether they were actually served, the decision should favor the defendant.

“I’m a lawyer. I’m about proof,” Voogt said. “There’s got to be better proof than the he-said-she-said contest.”

Proof, the app, provides that certainty by delivering constant information about the status of the documents. Using Proof, the lawyer or paralegal would upload the documents and the app finds one of its contracted process servers in the right area. The process server can pick up the documents printed at their nearest FedEx and the app then provides the GPS location, status and a means of directly contacting the process server throughout the process. The app has geolocation embedded into it as well, so if questions about their delivery arise, a judge can see when and where a party is served. The app in its current state also allows the process server to take a photograph. Voogt said he plans to later roll out a feature that includes an audio recording of the interaction.

Since launching in April, the app has rolled out across the Front Range and reached into Colorado’s mountain counties and the Western Slope. Voogt said he plans to build a national brand where there’s no consolidation into geographic areas and where there are no gatekeepers between law firms and process servers.

The app could bring some changes to process servers as well. Proof employs servers similarly to how Uber employs drivers. Servers can sign up to work with Proof, which cuts out the middle man, and incentivizes success by offering additional money on top of a base rate when they’re successful.

For Voogt, the creation of the app was a transition into the startup world. He’s scaled his legal practice down and now spends more and more time on the app as it scales up.

He said he works with some small clients, but by launching his own company, he got a taste of the startup lifestyle. Voogt started the company with 303 Software, a company that embraces tech culture — that caused a little bit of culture shock for Voogt. He said the company is very collaborative and works in a collaborative space with a different vibe from the law firm. He’s taking that mindset of technological disruption back to the legal world where he sees technology changing the law.

“Something that’s concerning to most of the legal world and the bar is the expense of representing clients,” Voogt said. “To do a lawsuit is very, very expensive. The hope and also fear is that technology is going to make legal services more affordable for the population.”

In the case of Proof, though, he believes the disruption is one lawyers are likely to embrace since it provides them with greater efficiency in a process that typically lacks it and does so without cutting into the legal work attorneys are needed for.

“It’s nice to be on front edge of that.”

— Tony Flesor