For the first time in the marijuana industry’s history, a patent on a cannabis product is the focus of a lawsuit in federal court. United Cannabis Corporation is suing Pure Hemp Collective, Inc. for infringing on a marijuana concentrate patent.

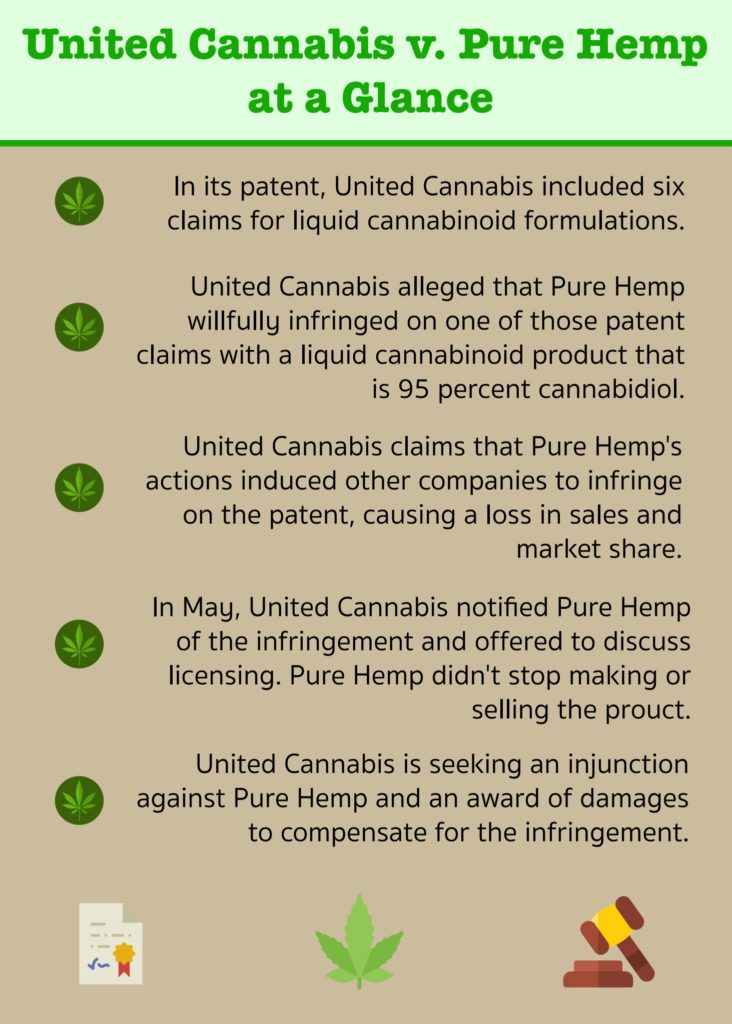

United Cannabis Corporation was given the patent in 2017 for liquid extracts of marijuana chemicals. Pure Hemp allegedly is selling a product that matches the patented formula. In United Cannabis’ complaint they specify a liquid extract that is 95 percent cannabidiol, a chemical often referred to as CBD.

After being awarded the patent in May, UCANN notified Pure Hemp of its infringement and offered to discuss licensing. It was alleged that Pure Hemp continued to make, advertise and sell the infringing product.

Vice president and general counsel of United Cannabis said in an email, “Our company places a high priority on innovation, research and development, and when it becomes necessary, we will protect our IP rights.” Pure Hemp did not comment on the case.

“It’s a case of first impression, you also have a situation where this is probably one of the first times that these types of companies doing this type of thing have appeared in federal court against each other,” said Justin McNaughton, a patent attorney at Greenspoon Marder.

This case is the first time a cannabis patent has the possibility to be enforceable and monetized. “It’s a bit of a double-edged sword because you have to enforce it in order to monetize it, “said David Gold, a partner at Cole Schotz who is in the intellectual property group as well as the cannabis law group. “You got to be very careful that you’re correct because if you’re wrong, you run the risk of losing your patent.”

Gold said he would make the argument that the patent should be invalid because it’s possible United Cannabis was not the first to make the product. McNaughton backs this up: “The idea is that if somebody had an extract that was more than 95 percent pure of CBD back 20 years ago, and that can be proven, then that claim is invalid.”

One of the official grounds for invalidation is if the invention has been documented to be in use prior to when the patent in question was filed. So while the case is about Pure Hemp infringing on a United Cannabis product, the main issue the case will likely grapple with is whether United Cannabis was actually the first entity to create these extracts.

Rachel Gillette, a partner at Greenspoon Marder who chairs the cannabis law group, doubts that United Cannabis invented the product. “The manufacture of this product to my knowledge has probably been going on for decades in the black market, but certainly has been happening for a number of years in the regulated marketplace too.”

McNaughton believes the patent is overly broad. The patent includes claims on six variations of liquid extracts, but the language is vague. The main patent claim in this suit just specifies a liquid that is 95 percent concentrated CBD. McNaughton says that the many companies that make extracts have products with concentrations of chemicals in the 95 percent range.

With a patent that broad, United Cannabis, UCANN for short, would be able to go after a large proportion of existing marijuana companies that manufacture extract with a high enough concentration of CBD, or any of the other chemicals they mention in their patent claims. That could be in the form of a cease and desist letter or a lawsuit.

David Gold, a partner at Cole Schotz, who works in the intellectual property group as well as the cannabis law group, said that companies with as broad of patents as UCANN issue 500 to 600 letters a year. The result of those letters is often an agreement to license the product for a fee instead of spending 10 times the fee or more in legal costs fighting the patent.

Out of the six formulations that UCANN claimed in its patent, the choice to focus on the one that is only CBD may have been purposeful. Law Week reported on the FDA approval of a CBD-based epilepsy drug, Epidiolex, earlier this year, which shows a slight shift in perspective from the federal government. Gillette cautions that outlook though, saying it’s “changing, but not changed.”

McNaughton thinks that the process of extracting and concentrating CBD also could have lagged behind the same process for THC. This would make it less likely that there is documentation of the product being made by someone before UCANN.

Gold says the court may dismiss the case because the patent is on something that is federally illegal, which would end the discussion for the time being. Gold thinks Pure Hemp may move to dismiss the case based on the court’s jurisdiction or for “unlawful subject matter.”

Gold summarized the stakes for UCANN, “Yes it could backfire in the sense that they’ll lose their patent, but…if they’re successful now they have a gold mine.”

— Connor Craven