Just as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation went into effect Friday with implications for U.S. businesses, a European Union development in patent law with implications for companies here, which has also been in the works for several years, had an important symbolic milestone late in April. The U.K. has ratified the Unified Patent Court Agreement, a system to create a single patent court with jurisdiction over all the EU’s participating countries.

The system also includes a proposed Unitary Patent to allow patent owners to hold one patent enforceable throughout the EU.

Currently, a central European Patent Office — which is independent of the EU — validates patents, but a holder must pay separate fees to validate the patent in each country. Patent attorneys in the U.S. and overseas say the U.K.’s ratification is a significant political indicator of the region’s commitment to participating.

But The UPC Agreement is on the clock, because two impending, intertwined events complicate its effectuation: a German constitutional challenge to the unified court, and Brexit, set to take effect at the end of March 2019.

Twenty-five of the EU’s member states signed the agreement in 2013. Thirteen member states have to ratify the UPC Agreement, and the U.K., France and Germany must be among them because the three regions hold a significant majority of patents in the EU. France has already ratified.

General consensus seems to say if if the agreement takes effect before Brexit occurs, the EU’s member states might more easily make a special agreement for an exiting member state to stay a part of the UPC system.

“The U.K. would really have to accept all the primacy of the EU law,” said Lucky Vidmar, a partner at Hogan Lovells. “If they do that, at least as far as we analyze it, we believe there wouldn’t be any legal impediment to them staying in. If you put your Brexit hat on, it’s unclear that all the Brexit-ers will be happy with accepting the primacy of the EU law.”

Vidmar and other patent attorneys say the agreement’s ultimate future, including the U.K.’s participation, is anyone’s guess. And that’s where a challenge to the agreement currently pending in Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court comes in.

Ingve Stjerna filed a complaint against the country’s ratification with a number of claims, including that the authority Germany would cede through the UPC Agreement is unconstitutional, and that the German federal parliament voted on the ratification laws with a simple majority, when they actually needed a two-thirds majority.

Tilman Müller-Stoy, a partner at Bardehle Pagenberg in Munich, said if the Federal Constitutional Court — the country’s highest court — dismisses the constitutional challenge as inadmissible and does not hold a hearing, the case could resolve in 2018. But if the court does hold a hearing, he said, the case’s resolution could be delayed into 2020.

“All of that is pretty much speculation, as the court can do what it wants to do,” he said. Müller-Stoy said experts and attorneys in constitutional law tend to believe the court will dismiss the case, but he expressed skepticism toward any perceived certainty about the ultimate resolution. Though the Federal Constitutional Court often chooses not to hold hearings and instead decides cases based on the written submissions, this case’s importance may prompt the court to schedule a hearing.

“Looking at the history, you will have noticed that lots of [parties] have filed amicus curiae letters with the constitutional court, there’s a lot of stuff to read, it’s being discussed all over he place,” Müller-Stoy said.

Brian Lefort, a partner at Faegre Baker Daniels who is also admitted to practice in Europe, said the region seems to have an economic interest in participating in the Unified Patent Court because it can promote technological innovation by protecting it. “I think they realize if they don’t participate, they potentially could be at some disadvantage economically for protecting their technology,” he said.

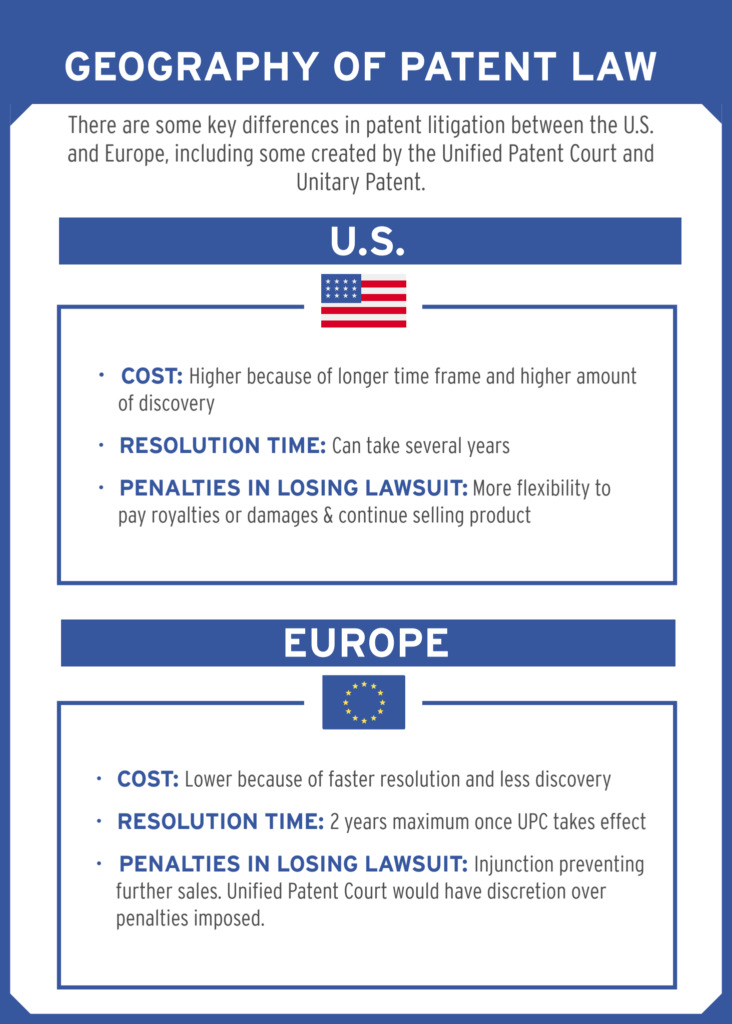

Effect on Patent Litigation

The UPC Agreement would come with a “sunrise period” beginning when it takes effect, and during the period patent holders would have the option to opt out of litigating their current patents in the unified court. For pending applicants, Lefort said, patent holders could choose upon their patents’ granting whether to subsequently litigate them in the unified court or in the individual states. Lefort said he expects large companies would have an interest in continuing to litigate separately in each country, because it makes challenging patents more difficult and larger companies have more resources for the fight. Additionally, they can continue enforcing their patents in other countries even in an instance they lose market exclusivity in another.

By contrast, Lefort said, medium-sized and smaller companies would have more of an interest in litigating in the Unitary Patent Court because of their more limited resources.

Under the current method of patent enforcement in Europe, losing a patent lawsuit typically results in an injunction preventing further sales of a product. Müller-Stoy said the Unified Patent Court would have discretion to either continue imposing such a penalty system, or allow more leeway to allow continued sales. He said he expects the court would likely do the former except in cases of extreme disproportionality, but as with the other issues hanging over the Unified Patent Court, it’s impossible to know for sure right now.

Müller-Stoy added while U.S. companies may know about the UPC Agreement at a bird’s-eye-view level, they may not have considered yet in-depth about how the system would affect the patents they hold in Europe.

“It is my personal feeling that most of the U.S. companies so far have said, ‘I’ll believe it when I see it; I’ll deal with it when it’s clear that it’s going to come.’”

— Julia Cardi