The history of the LGBT community in Colorado and its relationship with the state’s laws and government is a rocky one.

To learn the details of that relationship is to learn why activists are so concerned about the implications of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. The Supreme Court’s decision specifically touched on how Colorado erred in using laws to regulate religious expression, which is being seen by some, like Colorado State Rep. Daneya Esgar, to be a sign that discrimination based on sexual orientation is still something that must be fought.

CRIMINALIZATION OF HOMOSEXUALITY

The 1970s were generally a dark time for Denver’s gay men and transgender women. The Denver vice squad led by Captain Jerry Kennedy targeted the two populations.

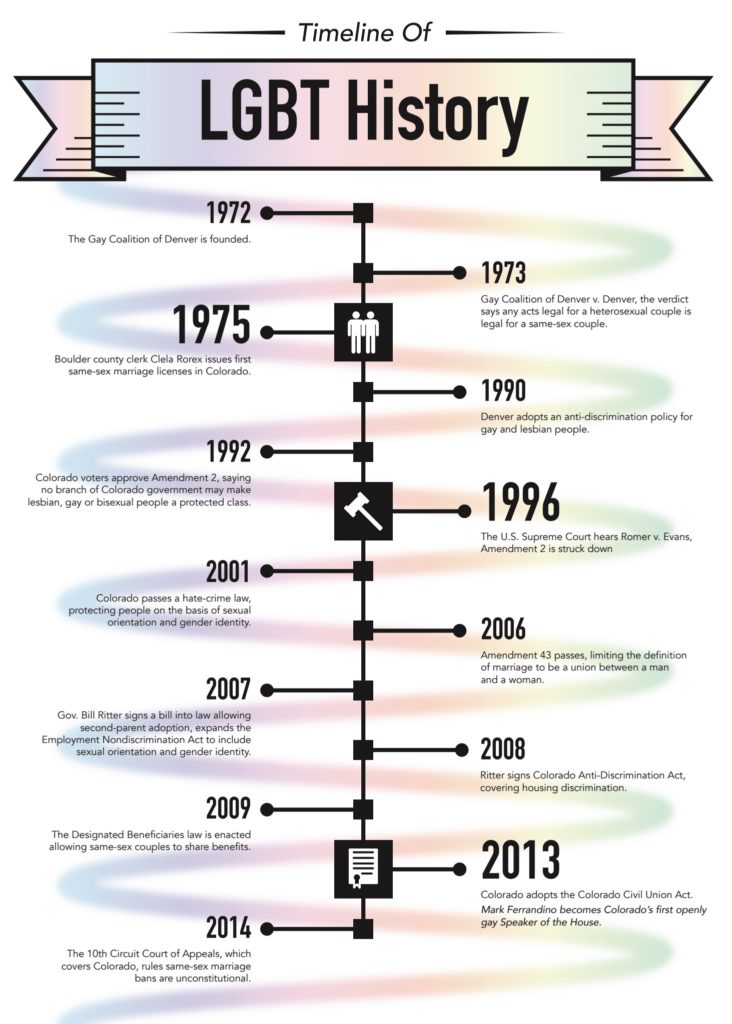

In 1973 Gerald Gerash and some friends established the Gay Coalition of Denver, which took on that police persecution. A 1973 lawsuit, Gay Coalition of Denver v. Denver, made public police records that showed 98 percent of people arrested that year for “offer of lewd conduct” were gay men. What followed was what Gerash calls the Gay Revolt at Denver City Council where 350 protesters came to a City Council meeting, and 35 people testified for three hours. The event marked a major shift in behavior for the city’s gays and lesbians.

“This was an extremely closeted city, and most of these people had never appeared at any protest, much less a gay protest,” Gerash said.

The next month, the City Council repealed four ordinances targeting the community.

That did not stop the vice squad from continuing their harassment. Plain-clothes officers would act as johns and arrest transgender sex workers. In 1977, Eugene Levi resisted arrest by Patrolman Daniel O’Hayre and was shot. In 1978 a transgender sex worker named Anthony “Irene” De Soto was killed by patrolman Lawrence Subia; the police report said she pulled out a pair of scissors and attempted to stab the officer, which gave him reason to shoot.

Former State Sen. and activist Pat Steadman recounted stories he heard from Paul Hunter, an openly gay attorney, about gay men being targeted for jaywalking outside Denver gay bar The Broadway and police taking their paddy wagon to do mass arrests at Cheesman Park under the guise that gay men were soliciting sex.

“It was really about attaching stigma to the individuals,” Steadman said. “The ticket for jaywalking or the overnight in jail wasn’t the penalty that was really impacting people. It was being outed.”

EQUAL RIGHTS

When Boulder county clerk Clela Rorex issued Colorado’s first same-gender marriage licenses in 1975, the idea of gay marriage wasn’t a concept the government expected to handle. At the time, marriage was not specifically defined as being between a man and a woman.

“My decision was based on what I thought was equitable,” Rorex said. “Someone stood before me asking for equal rights, I just couldn’t make a judgment to say no.” In total, she gave licenses to six couples, four male and two female. She was hounded with harassing phone calls and death threats, and former Colorado Attorney General J.D. MacFarlane issued an opinion that same-gender marriage was against the intention of the law. At that point, the district attorney’s office in Boulder recommended Rorex stop issuing the licenses. The state government never challenged the licenses, either legislatively or judicially.

The issue of marriage equality saw little change until 2012 when LGBT activists in Pueblo enacted a city ordinance to allow for same-gender domestic partner benefits for city employees, which gave many rights reserved for heterosexual couples to same-gender couples. At first the City Council tabled the ordinance indefinitely, and faced backlash from not only the LGBT community but also from their allies.

“We saw so many of our allies come out in support of that and show up to a town hall calling out the City Council members for tabling it,” said Esgar, a Pueblo native. “[The ordinance] instantly showed up on the next agenda and passed.”

Same-sex marriage was legalized statewide in 2014 when the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a ban in Utah, which set a precedent in Colorado. Although the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t take up the 10th Circuit’s case — Kitchen v. Herbert — it did solidify marriage equality across the country with Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT

Denver’s first Hispanic mayor, Federico Peña who was elected in 1983, broke new ground with the LGBT community by specifically campaigning with the community and even holding events at gay bars. The current Boomers Leading Change executive director Phil Nash said that with Peña’s election, “The entire tenor of politics changed in Denver, because it was shown that a candidate could win public office with visible support and endorsements from the gay and lesbian community.”

The 1990s and 2000s saw a significant amount of legal changes for the LGBT community in Colorado, both progressive and regressive. In 1990, Denver became one of the first cities in the U.S. to have an anti-discrimination policy for gay and lesbian individuals. Boulder and Aspen beat Denver to the punch in the 1970s and ’80s. In response came Amendment 2 to the Colorado Constitution.

“Its main objective was to create an impediment to the advancement of any law that recognized claims of discrimination based on sexual orientation,” said Steadman. The amendment would prevent any city, town or county from using any branch of government to protect gay, lesbian or bisexual individuals.

Activists, led by the Colorado Legal Initiatives Project, immediately took it to court. The lower courts halted enforcement of the amendment, and in 1996, Romer v. Evans made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 6-3 decision the court found that the amendment violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Five years after Romer v. Evans, Colorado passed a hate-crime law protecting people based on their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Gov. Bill Ritter signed bills of note into law while he held office as well, allowing second-parent adoption, expanding employment anti-discrimination protections for LGBT folk, creating protections in housing and public accommodation, and allowing same-gender couples to share benefits under insurance, inheritance, hospital visitations, funeral arrangements and death benefits.

Overlapping slightly and following Ritter’s years, the 2010s had a total of eight openly gay and lesbian legislators, including Steadman, Esgar and Rep. Mark Ferrandino, who was the first openly gay Speaker of the House in Colorado. The eight formed their own caucus, were good friends and communicated with each other frequently to keep up on opportunities to advance their advocacy.

THE CHANGING TIDES

Steadman became involved in LGBT activism in the 1990s when “it was not always safe to be an activist. It was not always safe to come out,” he said. “Over time, more and more people came out and public opinion, thankfully, evolved relatively quickly on these issues, there’s still a ways to go but when you compare where we’re at today to where we were 20 or 30 years ago, a lot has changed.”

Ferrandino started his political career working in Washington, D.C., in the early 2000s. When he talked to friends about his intention to move to Colorado with his eventual husband, they would ask him, “Do you really want to move to Colorado? It’s a hate state.”

Ferrandino said he is glad to see that progress that has been made on same-sex unions. In recalling his early days as a legislator he said, “We were just hoping we could get domestic partnerships and maybe civil unions, not even talking about marriage as something that is within the realm of possibility.”

Despite progress, some things Steadman and Ferrandino said they wish they had been able to get into law included a ban on gay conversion therapy. Also, Amendments 2 and 43 are still on the books here. If Obergefell is ever overturned, gay and lesbian couples would face a setback.

Steadman believes that the big-ticket items of the LGBT liberation movement have been accomplished in Colorado. He says remaining issues have become smaller in impact — such as rights of gay couples in senior living homes — but still are real and affecting people. Esgar is worried that complacency is taking root within allies, if not within the community itself, since Obergefell. She feels that the Masterpiece Cakeshop decision is evidence that there is still a fight to be had.

Ferrandino gave an account for how there is still not total acceptance of gay men. While he was the Speaker and after the passage of the Civil Union Act, the Denver Post sent a photographer to follow him for a day. A photo was taken of Ferrandino kissing his husband, which was put on the front page of the paper. “I realized very quickly how any thought that we had gone so far was overrated. The hate and bigotry and homophobia that outpoured after that was significant.”

Colorado was once not a very popular place for LGBT people, who boycotted the state in response to Amendment 2. Steadman, Ferrandino, and Esgar agree that Colorado is now one of the better states for people to live in and have equal protection. Esgar says, “We were called a hate state. We’ve come a long way since then.”

— Connor Craven